Beating Grammar and God into Young John Muir

In the end the thrashing taught the exact opposite lesson Muir’s abusive father intended.

Religion of a fierce, unforgiving sort drew Daniel Muir to move his family from Lowland Scotland to the Wisconsin frontier. He wasted no opportunity to instill in his eldest son his own fire-and-brimstone vision of salvation.

Set to clearing and burning brush on the homestead, John had to listen as his father turned the blazing fire into a lesson on divine retribution. Later in life he still remembered Daniel Muir saying:

“Now, John, just think what an awful thing it would be to be thrown into that fire — and then think of hellfire, that is so many times hotter. Into that fire, all bad boys, with sinners of every sort who disobey God, will be cast as we are casting branches into this brush fire, and although suffering so much, their sufferings will never end, because neither the fire nor the sinners can die.”

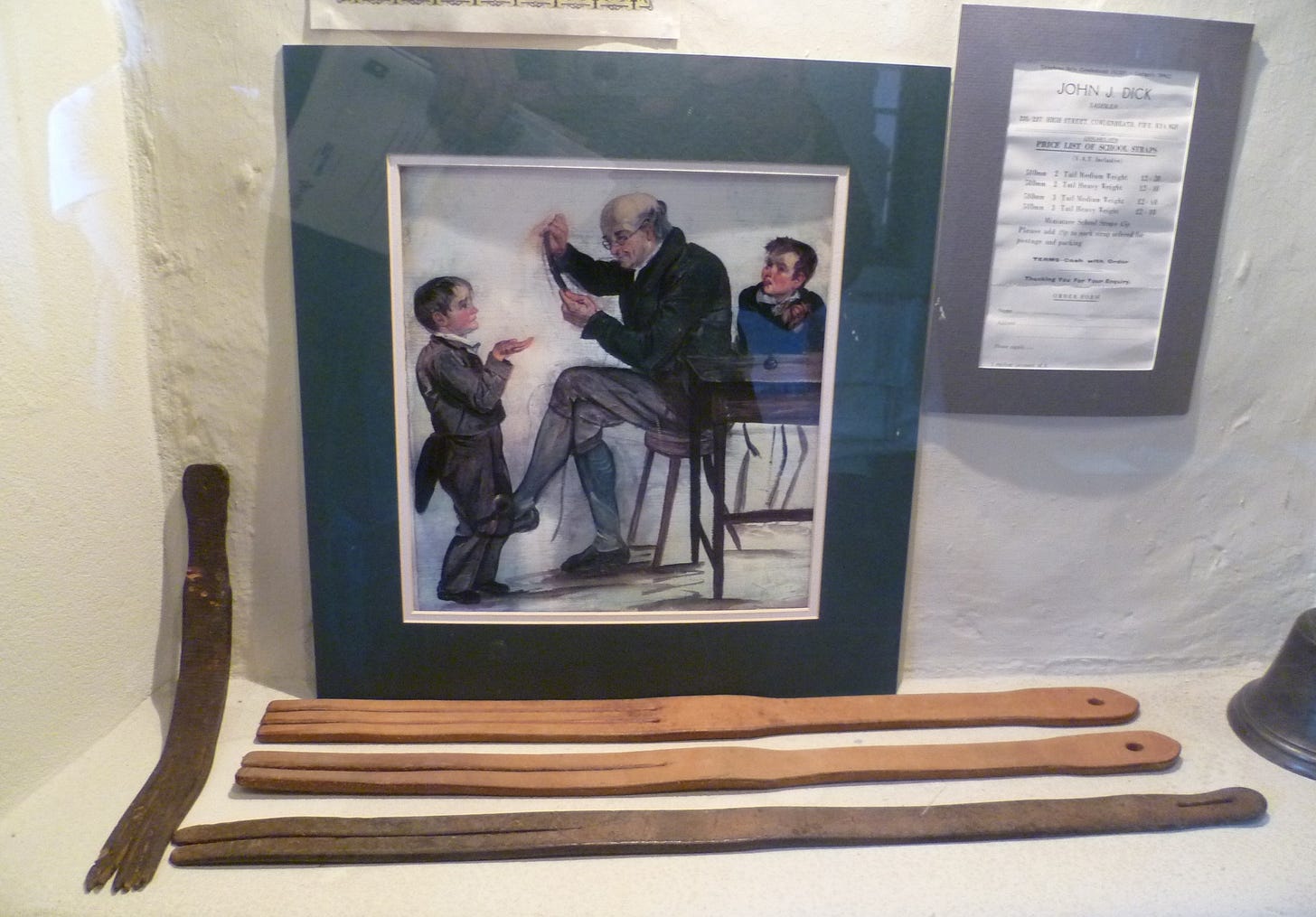

Back in Scotland, John was beaten both at school and at home, driven by pain to learn what a good boy was supposed to learn. The schoolmaster made liberal use of the tawse, a leather strap with a split end much favored for pedagogical punishment in Scottish schools. His father picked up where the dominie left off. Muir recalled:

Word lessons in particular, the wouldst-couldst-shouldst-have-loved kind, were kept up with much thrashing, until I had committed the whole of the French, Latin, and English grammars to memory…. In addition to all this, my father made me learn so many Bible verses that by the time I was eleven years of age I had three fourths of the Old Testament and all of the New by heart and by sore flesh.

Grade school for John ended when the Muirs came to Wisconsin, and his father made up the thrashing deficit at home. Painful Bible lessons continued, and Daniel Muir whipped John for any and every infraction of his myriad rules.

In Euro-American households in the 1850s, the rod was hardly spared. Yet, even by the abusive measure of the time, Daniel Muir stood out as vicious. Ann Gilrye Muir, John’s mother, knew her husband went far too far, so she used subterfuge to help John escape at least some of the violence. When he and his neighborhood friends were out past dark on Saturdays — a big no-no — she and he knew a beating would follow:

Late or early, the thrashing was for sure, unless father happened to be away. If he was expected to return soon, mother made haste to get us to bed before his arrival. We escaped the thrashing next morning, for father never felt like thrashing us in cold blood on the calm holy Sabbath.

Daniel worked John mercilessly through long, sweaty days of hard labor clearing the land and then farming it. The worst came after eight years of crude frontier farming exhausted the soil on the Muir homestead, and the grain crop dwindled. Daniel moved his family to another site, a few miles to the east, and began turning forest into farm all over again.

The high, dry site lacked springs, creeks, or lakes and needed a well to be habitable. Daniel set John to cutting through the sandstone to the water table with hammer and mason’s chisel. The bore had reached some 80 hard-hacked feet deep when father lowered son in a wooden bucket to resume work one morning. Nearly oxygen-free gas gathered overnight in the bore’s bottom quickly overwhelmed John. He passed out, then startled awake. Hearing his father calling from up top, a confused John fumbled his way back into the bucket. Daniel raised him to the surface and the clear, clean air he needed.

A stone mason neighbor showed Daniel how to dissipate the gas by dumping water down the shaft and dropping a bundle of brush or hay on a light rope again and again to mix the gas with fresh air. Confident that these measures would work, Daniel sent John back down into the hole to finish the job.

“Father never spent an hour in that well,”

John wrote, a line fairly dripping with resentment at the danger his clueless, punishing parent put him in. He made it clear, too, that the relentless beatings had failed to quash his spirit:

But no punishment, however sure and severe, was of any attraction to the lure of the fields and woods…. Wildness was ever sounding in our ears, and Nature saw to it that besides school lessons and church lessons some of her own lessons should be learned, perhaps with a view to the time when we should be called to wander in wildness to our heart’s content.

Nineteen years old when he dug the nearly lethal well, strong and lean and yearning for a wider and less punishing world, John Muir was building toward a break. His own inventiveness gave him the tools to engineer his escape.

No CAST OUT OF EDEN Next Week

I’ll be back in the woods up north, well off the grid and in the wild zone where wifi is only a distant dream. Back at it the following week.

,Thanks Bob,

Have a restful respite next week. Less than one month till we get the book!