Coming Attractions: John Muir’s Birthday and Earth Day

This annual near-alignment offers an ongoing lesson about wild justice.

Every year it happens: only one spin of the earth separates John Muir’s birthday on this coming Sunday, April 21, from Earth Day on Monday, April 22. The two dates aren’t actually related, but then again they are, sort of.

Muir had no more choice in the day he was born — April 21, 1838 — than any other human has. But Earth Day, celebrated annually since 1970, was intentionally calendared to build on the civic energy generated by Arbor Day. Declared a national holiday in 1882, Arbor Day happens on April 22, the birthday of J. Sterling Morton, the Nebraska newspaper editor who first called on Americans to spend a day planting trees. Earth Day has a similar impulse, and tree planting remains a major part of each year’s event, so April 22 made sense.

Earth Day focuses on protecting the environment, a purpose John Muir would have applauded. Indeed, some of his most important writing and advocacy helped turn Yosemite and its environs into protected national parks and created one model for what protection looks like. The U. S. lives still with the consequences of that strategy.

Muir’s campaign to protect Yosemite was grounded on two long, impassioned feature articles he wrote at the behest of Robert Underwood Johnson, the editor of The Century Magazine, then the most influential monthly in the country. A well-connected East Coast patrician with an inborn sense of the political pulse, Johnson put Muir’s articles before the U. S. Congress’s Committee on Public Lands and lobbied ceaselessly. The bill to protect Yosemite as a national park passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law on October 1, 1890, by President Benjamin Harrison.

Johnson and Muir were surfing a break in the zeitgeist: after two decades of fruitless debate about the destruction of public resources for private profit, Congress was embarking on a wild lands tear. Just a few days before Harrison’s signing of the Yosemite bill, he put his signature on another law that established Sequoia National Park in the Southern Sierra. The Yosemite law also contained provisions that set aside General Grant National Park, which protected many of the giant sequoia groves and would later be enlarged into King’s Canyon National Park.

In spring 1891, the U. S. Army dispatched two troops of the Fourth Cavalry to protect the new Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant reserves. The first order of business was getting rid of sheepherders who drove their all-consuming charges into the summer mountains.

Captain A. E. Wood, whose mission was to protect Yosemite, declared the flocks “the curse of these mountains.” He had an equally low opinion of the shepherds. They weren’t really Americans, after all, but “foreigners — Chilians [sic] … Portuguese, French, and Mexicans,” Wood sneered.

He came up with an ingenious method for dealing with the challenge. Any cavalry patrol that encountered a trespassing flock inside the park separated sheep from shepherd, then escorted the herder to one side of the park and drove the flock to the other. It took days for the shepherd to make his way back across the wilderness and round up what remained of the scattered flock. Rather than risk this financial loss, more and more herders steered clear of Yosemite and its military patrols.

Muir applauded the cavalry’s fast and focused work in turning the new national park into a fortress:

The smallest forest reserve, and the first I ever heard of, was in the Garden of Eden; and though its boundaries were drawn by the Lord, and embraced only one tree, yet even so modest a reserve as this was attacked.

Such attack required a fearsome defense, something the military was good at.

Although the tribal nations in the park weren’t “foreigners” like the sheepherders, the cavalry cut them no slack. Mounted patrols put an end to Indigenous deer hunts in the Tuolomne and Merced watersheds, which had been fully legal until those areas fell within the new park and its hunting ban.

Muir stood firmly behind this campaign to stamp out what he saw as a slothful crime against nature:

It is when the deer are coming down that the Indians set out on their grand fall hunt. Too lazy to go into the recesses of the mountains away from trails, they wait for the deer to come out, and then waylay them…. Central camps are made on the well-known highways of the deer, which are soon red with blood. Each hunter comes in laden, old crones as well as maidens smiling on the luckiest. All grow fat and merry.

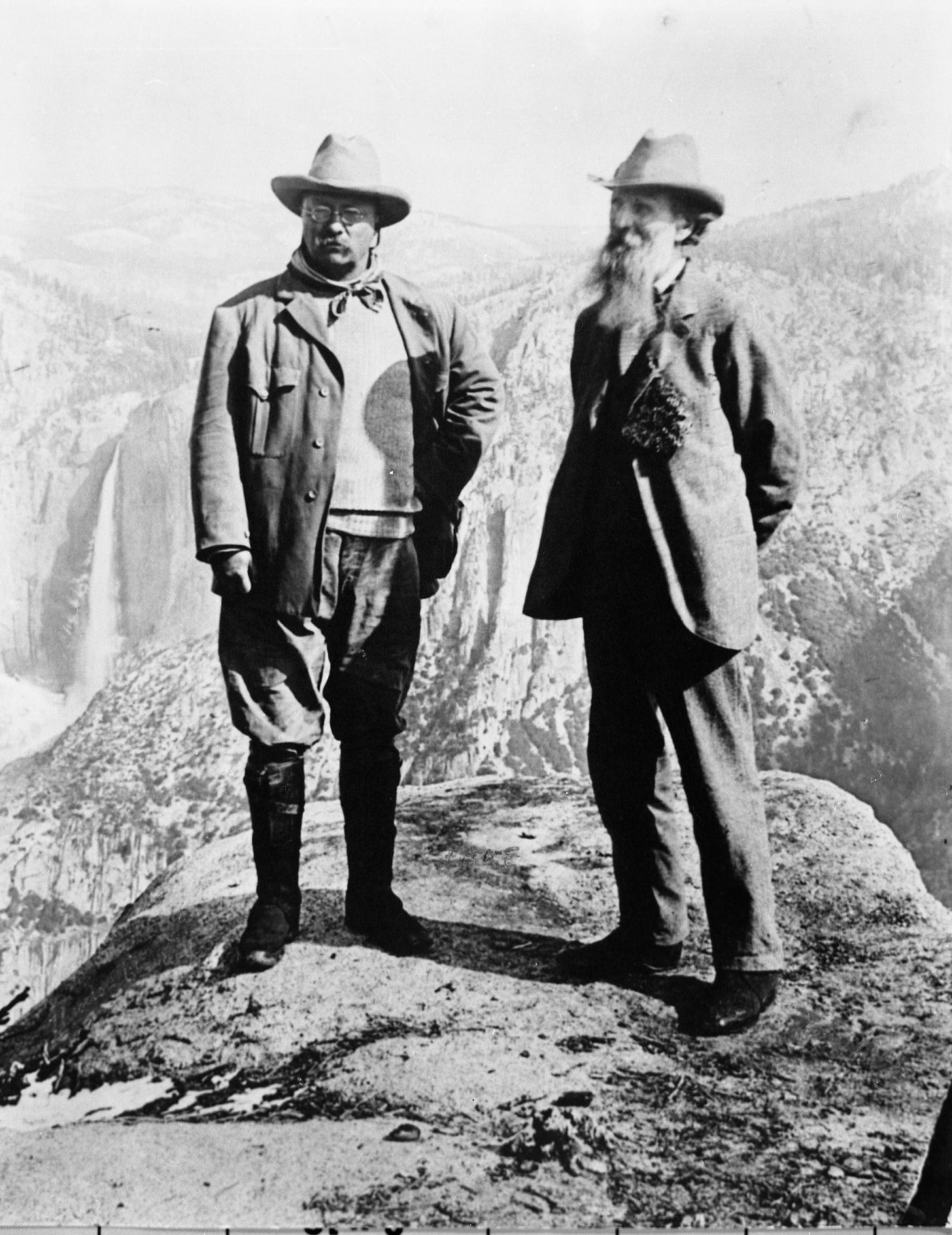

Muir never hunted, yet he was voicing the esthetic judgment of Teddy Roosevelt — who would later become an ally — and his fellow elite shooters in the Boone and Crockett Club. Trophy hunting in the fierce high country was the noble pursuit of manly outdoorsmen, while harvesting venison from ambush, the way Native Americans did, amounted to a lazy and cowardly outrage.

Never mind that the tribes and their ancestors had long lived sustainably with the Sierra Nevada’s fauna and flora and that forcing them out of what had been their homelands drove already dispossessed and impoverished peoples into an even more desperate corner. Fortress conservation depended not only on protecting wild land but also on picking and choosing who could thrive on its splendors. As a national park, Yosemite existed for tourists, hikers, and climbers — white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant, of course — not the tribal nations who had called it home for millennia.

The near alignment of John Muir’s birthday with Earth Day serves as a reminder. The earth does indeed need protecting, but not by keeping some people out and letting only certain others in. The better path lies in creating a system that both shelters the wild from destruction and allows diverse access to the sublime for all people and peoples. That amounts to no small challenge, one this country is only beginning to take up.

Less Than Two Weeks to Publication!

This is where the countdown gets exciting. Cast out of Eden rolls off the press on Wednesday, May 1. You can pre-order now and save 40% off the cover price. Be sure to use the University of Nebraska Press website and coupon code 6AS24.

Mark Muir’s Birthday and Earth Day at the Naturalist’s Historic Home

If you live in the Bay Area, a good place to celebrate the coincidence of Muir’s birthday and Earth Day is the John Muir National Historic Site in Martinez, CA. The National Park Service has put together a day’s worth of special events on Saturday, April 20. Details on JMNHS’s website.

Coming Book Talk

On Saturday, April 27, at 2 p.m. PDT, I’ll be talking about Cast out of Eden and taking Q&A with the Ina Coolbrith Circle, an SF Bay Area writers’ group. Free and open to all, on Zoom only. Please join me.