Coyotes in the Streets of the City

A chance encounter shows how wild critters are right here as well as out there.

Not that I’m unused to seeing, or hearing, coyotes. They have this way of showing up when I’m hiking and birding in the expansive open spaces and parks that begin only 20 minutes from my home. I’ve watched them hunt rodents in tall grass, strip ripe fruit from blackberry canes, and settle into a midday siesta. Still it surprised me early one morning to come out the patio gate behind my townhouse and see a medium-sized brownish critter quick-trotting down the sidewalk not 20 feet away. It threw me a sly side-eye without missing a stride in its bee-line trek across the parking area and into the quad beyond.

Before it was gone I realized this was no dog. No, no, no, it was a coyote. Right now, right here.

Mine is a dense residential neighborhood that borders a low-rise commercial strip a couple blocks over, and it sits the better part of a mile and a half from the nearest small open space. Hardly prime coyote habitat, but here was a critter synonymous with the Wild West showing up in what would appear to be a distinctly non-wild environment. Yet it wasn’t the coyote that was out of place; it was my thinking.

This reality and that memory of the coyote in the urban morning came home as I leafed through a recent New York Times photo feature on the coyotes of San Francisco. The city by the bay is home to some 100 of these wild canids, which do very nicely in the city’s various parks, sports fields, and other green refuges, living on mice, voles, rabbits, and the occasional discarded burger and fries. And San Francisco is hardly the only city with a coyote population that’s in it for the long haul.

Back in April 2020, when COVID lockdowns emptied America’s downtowns, photographer Michael Novo went to Chicago’s usually bustling Loop in hopes of shooting an eerily empty Michigan Ave. with a new camera he was trying out. As he told me in an email, when he set up the shot he heard something to the rear that he took to be a stray dog approaching. Instead, a coyote trotted past, centering the image of a city gone wild in the aftermath of apocalypse.

Yet shocking as it seemed, the critter’s appearance should have come as no surprise. The coyotes of Chicago and surrounding Cook County have been the research subject of Stanley Gehrt, professor of wildlife ecology at The Ohio State University (my undergraduate alma mater, no less), for over 20 years. As of the end of 2022, Gehrt’s team had tagged and catalogued 1,433 coyotes and developed a clear, data-driven picture of how they make their way in city and suburb.

For all the seeming oddity of their home range, Chicago’s coyotes do very well. They run a little larger and heavier than their rural cousins, live longer, and produce more litters over their lifetimes. And they do it all without making themselves nuisances to humans and our pets more than very occasionally.

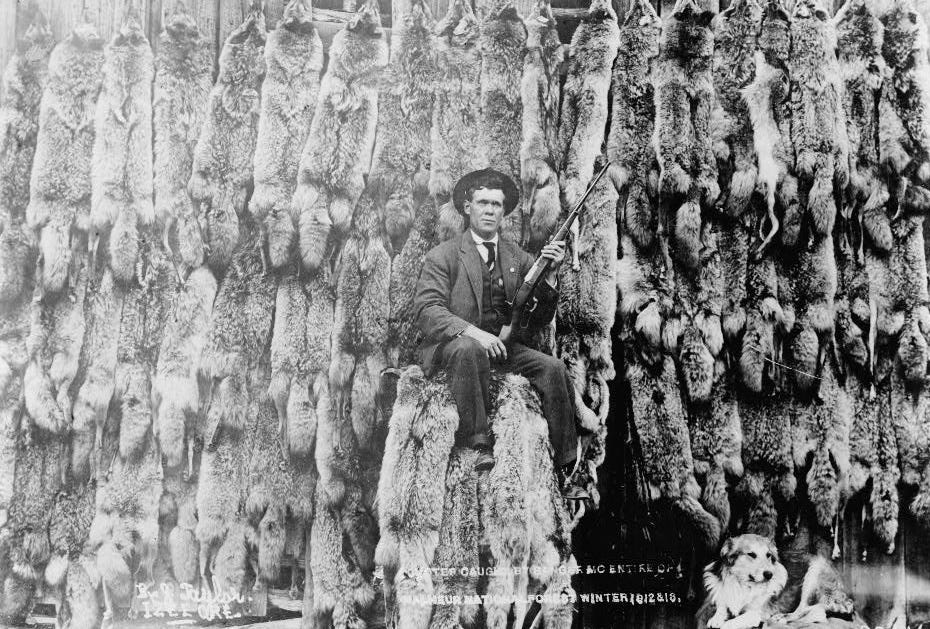

Coyotes are genetically equipped to push boundaries and to succeed in new surroundings. Back when Europeans first invaded North America, coyotes were native only to the deserts and scrublands of the West and to the Great Plains. Branded as pests, coyotes were shot, poisoned, and trapped with the same ruthless intensity as grizzlies, wolves, and cougars. Yet, unlike those other predators, coyotes pushed their range farther and farther. They can now be found from Canada and Alaska through Mexico into Central America and across the continent from the Pacific to the Atlantic and the Gulf. And, since the 1990s, they’ve taken up residence not only in Chicago, San Francisco, and my East Bay hometown but in practically every American city and suburb. Coyotes are clever survivors who know how to make their way in a changing world.

“Nature is not a place to visit. It is home.”

And they remind us of something crucial, even planet-saving. American culture holds to the notion that the human and cultural is a realm separate and distinct from the wild and natural, as if some impenetrable border wall divides the two. John Muir held fiercely to this point of view, seeing humans and their works as existential threats to the pure and pristine spaces he wished to preserve by walling them off against human invasion. The good thing is that his fervor, along with a more than a little help from Theodore Roosevelt, helped propel this nation into protecting spectacular places like Yosemite, Sequoia, Rainier, and Glacier from the unrestrained capitalist exploitation that would have turned them into garish, outdoor-themed Disneylands. Yet Muir failed to grasp, as do many of us today, that the wild and the human are interwoven into a complex, ecological fabric.

Urban coyotes remind us of the falsity of drawing a boundary between the human world and the wild. They demonstrate how humans and earth’s creatures, far from being separate, are connected in a single community of being. We’re all in this together.

“Nature,” writes the poet Gary Snyder, “is not a place to visit. It is home.” Every coyote, in the city or the country, and every other creature, both in our midst and in the wildest place imaginable, are telling us this same thing. High time to listen to our friends and neighbors.

Half off during Univ. of Nebraska Press’s summer reading sale

Through July 31, all of the press’s thousands of titles — including not only my Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age and Cast out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness but also great reads in poetry, fiction (Melissa Fraterrigo’s Glory Days), sports (Katya Cengel’s Bluegrass Baseball), politics, and Native American studies (Susan Harness’s Bitterroot), among other subject areas — are marked down 50%. Shop on the UNP website and use discount code 6SUMM25 on checkout. Happy reading!