Indian Field Days and Firefighting: Yosemite’s Genocidal Backstory, Part Three

For over a century after Yosemite’s conquest, tribal people lived and worked in the national park. That couldn’t last, of course.

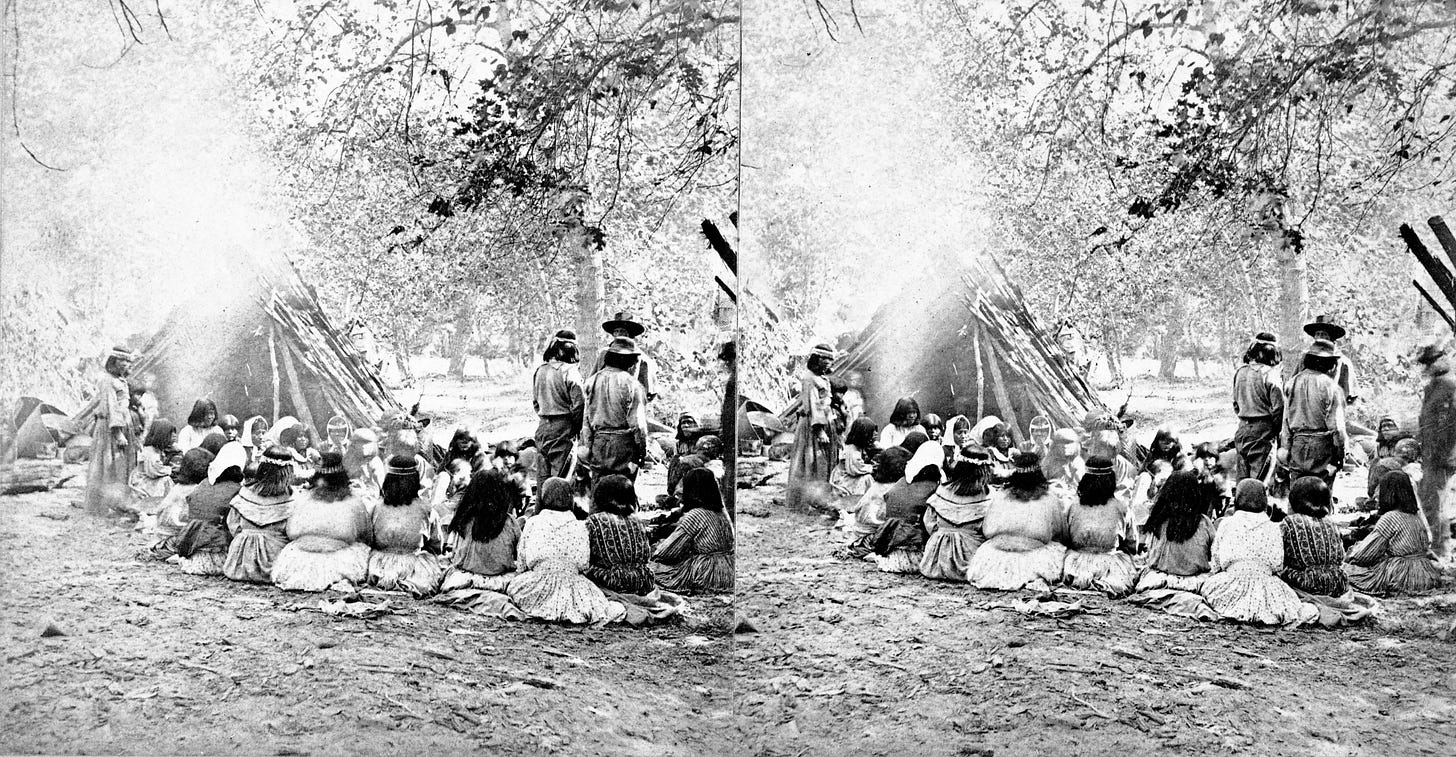

In the aftermath of the Mariposa Battalion’s rampage through Yosemite, stories of the granitic wonders to be savored in Yosemite Valley made their way to California’s growing cities. Soon tourists were coming to have a look for themselves, first by the dozens, then the hundreds and later the thousands. Visitors needed places to stay and meals to eat, and entrepreneurs seeing opportunity built crude hotels and dining halls to accommodate them. As the tourist business grew, some of the Yosemites and members of other tribes in the region filtered back into the valley, eager for an island of safety away from the vigilante violence of the goldfields and for a way to make a living.

Men built wagon roads, cut fence rails and firewood, fished and hunted for hotel dining halls, and wrangled horses and mules. Women cleaned guests’ rooms, washed their linens, and cooked and served their meals. By the time the federal government turned control of Yosemite Valley over to the state of California in 1864 as a preserve “for public use, resort, and recreation,” tribal people were once again living year-round in the valley, settling back into village sites they had been expelled from a decade earlier. These workers became so woven into the valley’s economy that they formed the principal source of wage labor even after the valley was added to Yosemite National Park in 1906.

Ten years later, the newly formed National Park Service turned the park’s tribal people into the summer spectacular known as Yosemite Indian Field Days. The event featured a rodeo, bareback horse races with painted riders, and an arts and crafts fair. Tourists did come, eager to see “authentic” Native Americans in a scenic setting and buy souvenirs. Still, the event didn’t draw enough spectators and buyers to make up for the decline in visitors and revenue Yosemite experienced in late summer, when waterfalls dwindled to an unimpressive trickle or dried up altogether.

To draw more paying customers in the off season, Chief Ranger Forest S. Townsley decided to refashion the Field Days along the lines of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. He recruited Indigenous people by the dozens, dressed them up in buckskins and feather headdresses, and erected canvas teepees. It hardly mattered that the Yosemite tribes had never lived in teepees nor worn feather headdresses. Those props said “Indian” to Euro-Americans, and Townsley wanted to give white folks what they came for. In the process, the Field Days transformed from a rough-and-tumble rodeo into a major exhibition of Indigenous crafts, particularly finely woven baskets. Crowds of Euro-American consumers came to buy their bit of Native American exoticism before it vanished from the earth. By the mid-1920s the craft fair had become a bigger draw than the rodeo.

The NPS’s emphasis on manufactured authenticity hit a comic high when Hazel Hogan, crowned Miss Yosemite and dubbed White Fawn for the event, swapped her dark, tight braids for a stylish marcel. NPS official Herbert Wilson threatened to fire Hogan if she didn’t dump the marcel and go back to the braids. He knew that the last thing incoming tourists were interested in seeing was a thoroughly modern Indigenous maiden.

There was a problem, too, with Yosemite’s Indigenous workers’ cars. Seeing a tribal person driving an automobile, even a Pontiac with its Indian-head logo, rudely pricked the bubble of throwback, befeathered authenticity tourists craved. To keep reality from puncturing fantasy, the NPS told Indigenous drivers to park on a back lot and keep their vehicles out of tourists’ sight.

Housing posed another branding challenge. At the turn of the century, the valley’s tribal residents lived in six small villages. The year after Yosemite Valley was added to the national park, the newly arrived U.S. Cavalry forced the residents out of Koomine village at the base of Yosemite Falls and burned their shelters to clear the site for the first military outpost in the valley.

By 1910, the five remaining villages had consolidated into one — partly by force, partly to take better advantage of job opportunities in the ever-growing tourist business. The community came together in the long-occupied village of Yawokachi (Yó-watch-ke) — Indian Village to the NPS — a sunny location at the mouth of Indian Canyon that offered the valley’s warmest winter days. Some families lived in umuchas, traditional, conical structures built of cedar bark. Others occupied shelters constructed from cast-off military tents and makeshift shacks cobbled together from scraps and discards. Nobody had electricity or heat apart from firewood, so they didn’t pay utilities, and NPS charged no rent. The umuchas clashed stylistically with the NPS-constructed teepees on the fairgrounds, puncturing yet again the bubble of faux authenticity. Plus, NPS brass saw the tent-cabins and shacks as seedy and rundown, more hillbilly than “noble savage.”

Yawokachi became an issue demanding solution with the 1927 opening of the luxurious Ahwahnee Hotel, located just down the road. The NPS first planned to let surrounding vegetation grow into a barrier that shielded high-paying guests’ eyes from the village. Then, encouraged by the Yosemite Park and Curry Company, which owned and operated the hotel, the NPS decided it would be better to raze Yawokachi and move its people somewhere out of sight. Once that decision was incorporated into the park’s master plan and Yawokachi’s residents caught wind of it, the NPS lost the grassroots support and cooperation it needed to keep Yosemite Indian Field Days alive. The last event was held in 1929, the same year that Hazel Hogan had to change her hairstyle and Indigenous car owners were told to park out back.

Indeed, authenticity was coming to mean ridding Yosemite Valley of the Yosemites.

By then the NPS had decided it was time to move on. Horse races, rodeos, and craft fairs were unknown among the Yosemites before Euro-Americans took control, the institutional reasoning ran, so Indian Field Days hardly qualified as authentic. Indeed, authenticity was coming to mean ridding Yosemite Valley of the Yosemites.

Claiming that the new medical center to be built in the valley needed Yawokachi’s spacious, sunny site, NPS again told the village’s residents they had to move. They were consigned to a site west of the Camp Four campground, out of sight and out of mind in a former village site they called Wahhoga (Wa-hó-ga). NPS entertained the notion of erecting faux teepees yet again, but that bad idea soon died. In the end, the government settled on a three-room cabin that measured only 429 square feet, with no plumbing except a kitchen sink and a wood stove for heating and cooking. Some of these fifteen tiny homes housed families of six to eight adults and children crammed into far too little space. That was part of the plan: cramped quarters would keep what park officials considered tribal riffraff from slipping into the valley and settling in.

Moving the Yosemites was just the opening gambit. Pushing them out of the park, Park Superintendent Charles Thomson told his superiors, “would remove the final influence operating against a pure status for Yosemite.” Since the federal government owned Wahhoga’s cabins, it now completely controlled the housing situation. For the first time residents had to pay rent and utilities, and NPS limited residence to people employed by NPS or a concessionaire in a job eligible for retirement. And, should residents fall behind in the rent, lose employment, or retire, they forfeited any right to remain in the valley and had to move out.

The situation worsened after World War II when NPS tripled rents without boosting wages. This money crunch did little to soothe the growing antagonism between bureaucrats and residents. Bad feelings worsened when the qualification for residence in Wahhoga was further limited to only a permanent government job. Those who did not qualify were given four weeks to clear out, then their vacated cabin was torn down. That way, neither they nor any other Yosemite family had a home to come back to.

Year by year the attrition continued, helped along by occasional chicanery. One Wahhoga elder told of NPS assigning her husband to a work detail in the backcountry, then evicting her and their children while he was away. He returned to find them gone, like so many others before and after.

By 1960 only three cabins remained. Nine years later, the few remaining residents were evicted and relocated to a government housing project, and the last Wahhoga cabins were set aflame to provide a practice session for the park’s firefighters.

Yosemite had been cleansed. In the eyes of the Park Service, wildland purity, the preservation of the pristine, required no less.

Cast out of Eden events in the offing

On this Saturday, Aug. 10, 7 p.m. PDT, I’ll be reading from Cast out of Eden, talking about John Mjuir and Native California with poet and writer friend Moira Mattingly, and taking questions from the audience at The Bookery, 326 Main St., Placerville CA. Free and open to all.

The following Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2 p.m. PDT, I’ll be talking about the book and taking Q&A under the auspices of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at California State University East Bay, Concord Campus, 4700 Ygnacio Valley Rd., Concord CA. Please register in advance here.

Fascinating and so sad. It brought back memories of my parents, in the late 50’s, taking me to the Wisconsin Dells. We took a boat one evening down a small waterway, there were Native American villages on the banks- and at one point a Indian man on one cliff was singing “Indian Love Call” to a women on the opposite bank. This is so pre Disney. I remember it like it was yesterday. At the souvenir shop, I was allowed to buy a beautiful Indian doll. I treasured that doll so much! This is so like what you describe happening here in Yosemite. I’m embarrassed how clueless we were and are still. You are doing such great work- educating us all! 🙏