John Muir and E. H. Harriman, Redux

In their time, the alliance of the wilderness influencer and the railroad tycoon made political sense. It took on a personal dimension as well.

Back in my UC Berkeley days when I first encountered John Muir, I took it for granted that the founder of the Sierra Club, as bearded and long-haired as any Sproul Plaza regular, favored the same leftist views as my similarly adorned grad school colleagues and I. That assumption proved false. Back in Muir’s time, business-oriented conservatives and wild-land preservationists joined forces over protecting the West’s spectacular landscapes. So it was that John Muir, the country’s leading wilderness advocate, formed an abiding connection with E. H. Harriman, one of the most powerful business leaders of the era.

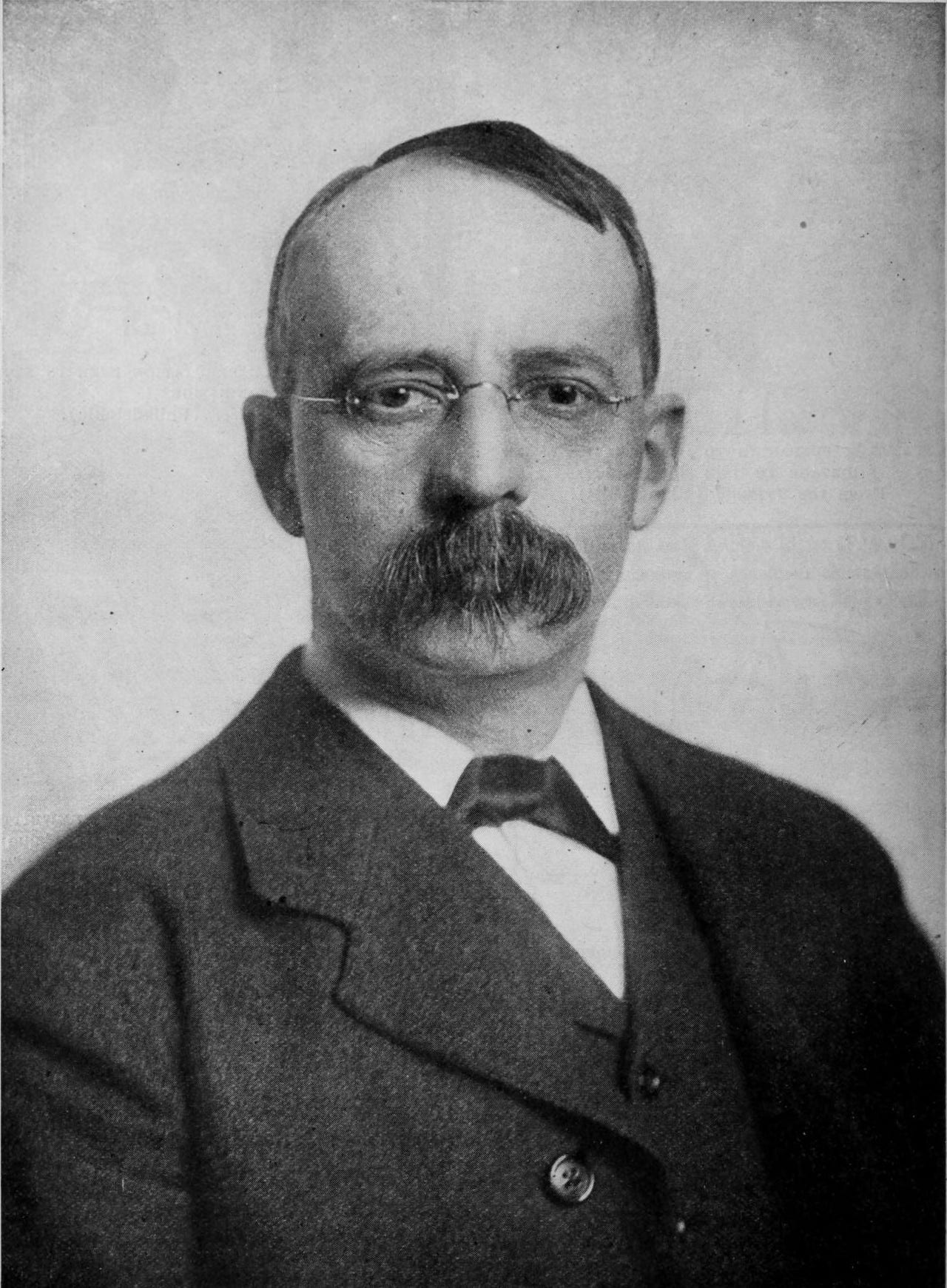

They met serendipitously. C. Hart Merriam, head of the Department of Agriculture’s Division of Biological Survey, was at work in his Washington, D. C., office one day when, utterly uninvited and unknown, a middle-aged man walked in. Although he acted like he owned the place, Merriam’s visitor cut a less than impressive figure: short stature, thinning hair, a dark and expressionless face atop a pugnacious chin, and a drooping mustache described by a friend “as unkempt as if it had been worn by a Skye terrier.” It surprised Merriam to learn that his visitor was railroad magnate Harriman, who had just succeeded in an epic takeover of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Worn out from boardroom battles and corporate infighting, Harriman wanted to kick back for a good, long time in a place far, far away. A dedicated outdoorsman and hunter, he decided that stalking the Kodiak bear, largest ursine on the planet, would give his soul the reboot it needed. Merriam had authored the scientific paper identifying the Kodiak as a subspecies of the Alaskan brown bear, and so it was that Harriman sought him out.

The railroad baron made the astonished Merriam an offer too good to refuse: Harriman wanted to invite a select group of senior scientists — all expenses paid, of course — as a way of transforming his bear-hunting outing into a grand scientific expedition. Would Merriam join the effort and select the scientists?

And so it was that Merriam asked Muir to come along as the expedition’s glaciologist. Uncertain about the notorious Harriman, Muir accepted at the last minute only because the trip would give him a chance to see stretches of the Alaskan coastline he had yet to visit.

The group assembled in Seattle at the end of May 1899 and boarded the George W. Elder, a one-time Inside Passage tourist ship overhauled and elegantly refitted by Harriman’s Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company. With the Harriman family and friends, assembled scientists and artists, a squad of professional scouts and packers, and captain and crew, the Elder was carrying 126 people north. John Muir, legendary saunterer of high mountain solitude, numbered now as but one among a crowd of early, elite ecotourists and their myriad minions.

Muir’s focus on the Harriman Expedition was glaciers, long a fascination of his. He filled his journals with sketches and notes about the many rivers of ice that came out of the mountains and down to the sea. And when the expedition encountered an unnamed glacier at the head of a fjord in Prince William Sound, Muir proposed that it be dubbed the Harriman Glacier by way of expressing gratitude to the Elder’s generous host. That idea raised a cheer from the scientific party, and Harriman thanked Muir for gracing the glacier with his name. To this day it is known as the Harriman Glacier.

This gesture wasn’t simple sucking-up to Mr. Money Bags. Muir tended to distrust magnates and tycoons, and that had been his attitude about Harriman before he came aboard the Elder. But as the skip bore north and west and Muir befriended Harriman’s children — he always had a soft spot for kids — his initial skepticism gave way to respect.

So it was that Harriman, working behind the scenes like the puppet master he was, helped Muir pass the state and federal legislation that moved Yosemite Valley from California’s control into the federal Yosemite National Park. Yet, more than convenient allies, Muir and Harriman became friends, confidants, and companions.

In the summer of 1908 Harriman invited Muir to come and stay with him and his family at his recently acquired lodge on Pelican Bay in Oregon’s Upper Klamath Lake. Harriman had purchased the place as a wilderness getaway, plus it offered him a strategic perch to oversee the Southern Pacific’s expansion into the region and be sure he left no money on the table.

When Harriman’s invitation came, Muir at first begged off, explaining that he was hard at work on his autobiography and too bogged down in the vexing project to leave it. Phooey, Harriman wrote back, “you come up to the Lodge and I will show you how to write books.” Muir did come up, and when his writer’s block continued, Harriman had his personal secretary follow the naturalist around, capture his musings in shorthand, then type them for review. The process worked so well that Muir stayed most of the summer, working the whole time. He had a serviceable first draft in his bag when he and Harriman left Upper Klamath Lake to travel together to Portland — by rail, of course.

“At the stations along the road,” Muir wrote of Harriman’s triumphal progress across Oregon:

He was hailed by enthusiastic crowds assembled to pay their respects, recognizing the good he had done and was doing in developing the country and laying broad and deep the foundations of prosperity.

Early the next year, during a trip to Arizona and Southern California, Muir detoured to consult with Harriman over the Colorado River flood that had inundated much of the Imperial Valley, wiped out the town of Mexicali just across the border in Mexico, and created the Salton Sea. As they walked and talked about the engineering challenge of returning the great river to its original course, Muir surely noticed that Harriman was looking unwell. The normally stoic tycoon complained of an ever-worsening upset stomach that dulled appetite and drained energy. Soon thereafter the malady was diagnosed as stomach cancer too far along to treat. Harriman died, only age 61, before the year was out.

The death hit Muir hard; his circle of friends and family was fast shrinking. Long-time close friend Joseph C. LeConte had died of a sudden heart attack on the first Sierra Club summer camp-out in Yosemite Valley. Next, wife Louie passed on, leaving Muir unmoored and bereft. Daughter Wanda had married and moved away, and daughter Helen was about to do the same. Harriman’s passing capped Muir’s string of heartfelt losses.

He confided his sorrow to fellow writer John Burroughs in a letter:

I feel very lonesome now my friend Harriman is gone. At first rather repelled, I at last learned to love him.

Next up: When the Harriman Expedition sacked a Tlingit village for souvenirs.

Cast out of Eden heads to Stockton

On Monday, Nov. 4, 5:30–6:30 p.m., at an in-person event sponsored by the University of the Pacific's John Muir Experience and the Sierra Club's Delta-Sierra Group, I'll talk about Cast out of Eden, take questions and comments from the audience, and sign copies. Free and open to all, no advance registration needed. Fireside Room, Central United Methodist Church, 3700 Pacific Ave. (across from the University of the Pacific), Stockton, CA 95204.

Still time to save half off on Cast out of Eden and The Modoc War as well as all Bison Books titles

Through October 31, the University of Nebraska Press is offering a 50% discount on the many titles in its prestigious Bison Books trade imprint. Shop online, then use discount code 6BB24 at checkout.