John Muir’s Money

The wilderness advocate amassed an estate worth $6.5 million in today’s currency by profiting from an agricultural revolution built on California’s racial hierarchy.

After years spent tramping the High Sierra and making three long trips to Alaska and the Arctic, often while on newspaper or magazine assignment, John Muir came to the realization most writers face: putting words on paper is a hard way to make a living. Early on, the money he picked up from writing provided cash enough, especially for someone as frugal as Muir. Now his life had changed. He was a recently married man and a brand-new father, and he needed something steadier, something more lucrative.

Muir had married late — he was 42, wife Louie 33 — but well. John Strentzel, Louie’s father, was a Pole expelled as a young man from his partitioned homeland for taking part in a revolt against Russian rule. Strentzel studied medicine in Budapest, then came to the United States, where he started a medical practice and a family and in time settled on 20 acres outside Martinez, California. Gentle climate and good, well-watered soil made it a perfect choice to pursue his deepest passion: horticulture.

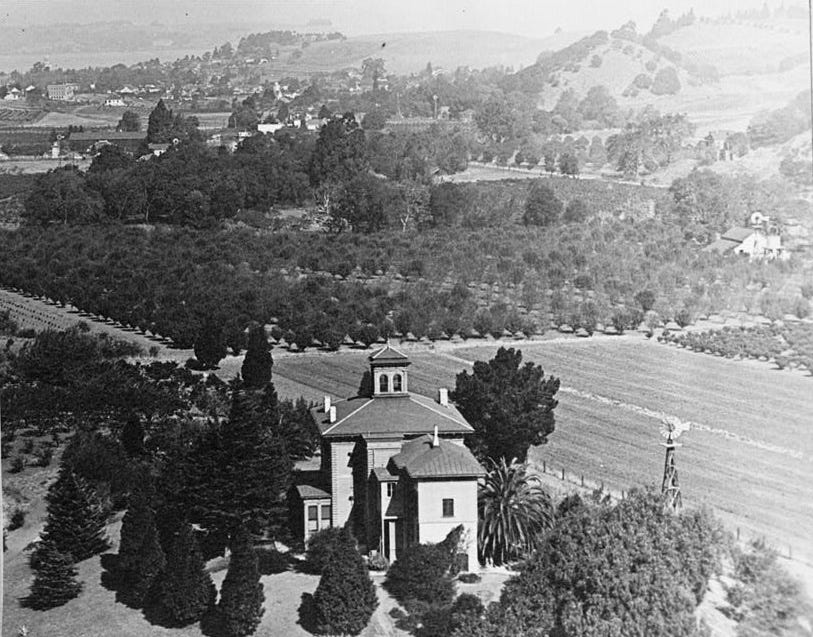

Besides raising cattle and growing hay and wheat, the staple money crops of the time, Strentzel experimented with a capacious variety of fruits and vegetables: apples, pears, peaches, plums, apricots, figs, cherries, currants, blackberries, gooseberries, strawberries, sugar beets, oranges, almonds, grapes, and olives. He plowed the modest profits of this abundance into acquiring more land. Eventually he owned over 2,300 acres as well as whole blocks of fast-growing Martinez and its waterfront.

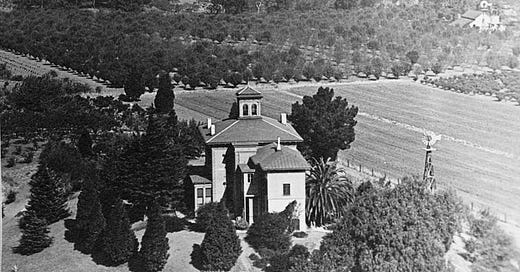

When John and Louie married, John Strentzel welcomed his new son-in-law into the family and onto the farm, treating him as the heir he would become. The Strentzels made a wedding present of their Dutch Colonial cottage to the new couple and began building the seventeen-room, Italianate Victorian mansion atop a commanding knoll where they would live out their days. Strentzel shifted more and more management responsibility onto his eager son-in-law; soon Muir was handling day-to-day farm operations and on his way to becoming the man in charge.

Even as Muir was stepping up, California agriculture was undergoing a sea-change. Under Spanish and Mexican rule, California’s farms and ranches, many on mission lands, served to feed the colony and profit friars and ranchers. Hides and tallow from semi-wild herds of cattle that roamed the grasslands were the principal cash export. Fruits, vegetables, and grains were grown and consumed locally through the gold rush and into the early years of statehood. By the time the gold played out, wheat had replaced hides as California’s principal export.

Yet California’s unique competitive advantage lay far less in cattle and grain than in a climate ideal for raising perishable, even exotic fruits and vegetables, from wine grapes and olives to salad greens and asparagus. Although California’s population was growing fast, particularly after the Civil War, local markets could absorb only so much of this varied abundance. Meanwhile, the distant, urban East was swelling with a rapidly expanding middle class that had money to spend. How could California’s perishable produce take advantage of this alluring opportunity on the far side of the continent?

The first part of the answer came when the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. With the lowering of freight rates through the 1870s and 1880s and the development of the refrigerated car, those booming, distant markets in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago moved within the reach of California growers. By the late 1880s, the weight of fresh fruit shipped east increased from a little under 2 million pounds annually to almost 54 million. The California fruit boom was on.

Not only the infrastructure and production but also the culture and strategy of California agriculture were shifting. Horticultural utopians like John Strentzel faded into the past and became nostalgically quaint romantics as younger, profit-driven agricultural capitalists took over. These new businessmen of farm and field recognized that large growers were more strategically positioned to benefit from rapid technological change than were small-scale operations. And they saw that specialization in the few most profitable crops would yield far better returns than horticultural diversity. California growers set about creating an industrialized agriculture unlike any seen before in the U.S. The goal now was not more crop varieties but more money, always more money.

Muir made this paradigm shift his own; he aimed to be a successful businessman whose vision focused on the bottom line. His first task was to reshape his land.

Alhambra and Franklin Creeks coursed through the farm, their banks thick with trees and brush and prone to flood during heavy winter rains. Muir and his farmhands cut trees and shrubs in the creeks’ lower stretches, fired the underbrush, planted exotic eucalyptuses and cedars higher up the flow for shade and firewood, then dug irrigation ditches to carry water from creeks into croplands. In the course of this difficult and dirty work, Muir dove into more than a few poison oak thickets. Once he developed a rash so bad that his eyes swelled shut, and he had to spend several days in bed, mostly blind and itching madly all over.

Muir’s campaign to control extended not only to the watershed but also to the unwanted creatures that infested crops and lowered yields and profits. Ground squirrels that burrowed in and around the roots of trees and vines, fruit-eating birds like house finches and California quail, and insects from scales to cutworms had no place on the farm. The move into intensive agriculture replaced a complex, diversified, natural ecosystem with a simpler landscape that invited invasion by hordes of daunting pests.

Controlling them, like stream clearing, resulted in personal injury. During the mixing of a rodent poison that contained white phosphorus, which ignites on contact with air, a sudden burst of flame set Muir’s clothes afire and burned him severely.

Despite the cost to his body, Muir kept at it even while lamenting that “I am losing the precious days. I am degenerating into a machine for making money.” He focused intensively on the most popular and profitable crops to gain the business advantages of scale. Muir converted the 30 acres that John Strentzel had used for hay and grain into grapes, then added more and more acres of vineyard. Within a few years he became the state’s largest supplier of fresh tokay table grapes. The pear orchard that once produced sixty varieties was converted to Bartletts alone. He made no apology for raising little besides tokays and Bartletts. “Give the people what they want,” Muir said.

As a formula for business success, his strategy worked. Where John Strentzel in his heyday had sold hundreds of crates of fruit and made a modest living, Muir was selling thousands and gaining a reputation as a hard bargainer among the San Francisco wholesalers who bought his crop. And, like every California grower who went all in for intensive, large-scale fruit production, Muir needed seasonal on-demand labor at the cheapest possible cost.

That’s where the Chinese came in.

Up next: California, a Native slave state.