Journal Trumps Memoir

To discover the truth of the moment, trust words written at the time, not later, when the writer may have a different agenda. Let me explain.

One key to making narrative nonfiction work is revealing the characters’ emotional reactions to events as they unfold. Raised hope, for example, helps create suspense, a point Adam Hochschild made in talking about Spain in Our Hearts in the class I took from him earlier this year. And to uncover that emotion as it unfolds, Hochschild continued, rely on journals over memoirs.

Written years or even decades after the events they describe, memoir has this way of creating narratives that reflect a story in the writer’s current, not past, incarnation. This isn’t as dishonest as it may sound. All of us over time shift the stories we tell about our pasts, sometimes because we understand them better, sometimes because we find ourselves embarrassed or alarmed by what we did and felt back then. Memoirs can serve as a way of cleaning up old stories for current consumption.

All this applies to getting at the truths of John Muir’s life. By the time Muir got around to writing about his early years, he was in fact an elder, a wilderness influencer with a well-honed public image. Here’s a telling case in point.

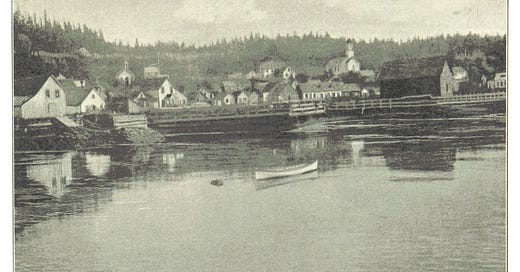

In 1879 and 1880 Muir made two trips to Alaska, covering the Inside Passage from Fort Wrangel — now called Wrangell — to Glacier Bay in dugout canoes captained and paddled by Stikines, one of the Tlingit tribes native to this long reach of wild, wondrous coast that the United States had purchased from the Russian Empire in 1867. The Tlingits were furious about the sale, saying Alaska was theirs, not the Russians’, and they set to resisting American hegemony.

The U.S. military soon displayed its willingness to crush that Tlingit resistance. The naval side-wheeler Saginaw turned its cannons on the village of Kake and destroyed it. Then, when the Stikines in Fort Wrangel refused to surrender a man accused of murder, the American army shelled their village. The accused was given up and quickly hanged, his breathless body left on the gallows until nightfall to teach the Stikines a lesson.

As far as the newly arrived Muir was concerned, such brutal repression had been and still was what the Tlingits needed. He told his journal so in mid-July 1879:

... good thrashing, prompt, heavy and wholesale and whole-souled, discriminating only as to the offending tribes, not as to individuals. It is a common saying that savages respect only power; these seem literally to kiss the rod and love it, and therefore need it only once in a lifetime.

Punishment was, Muir was certain, grooming the Tlingits for civilization:

They are industrious, willing to give good and fair work for fair wages, and to adopt all of the benefits of the uneducated of any people under the sun. Unprincipled whisky-laden traders are their bane…. A few good missionaries, a few good cannon with men behind them, and fair play, protection from whisky, is all that the Alaska Indians require.

Written only three years after Custer’s destruction on the Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn), this passage was hardly surprising for the time. Even though Muir was generally anti-war, he, like most white Americans, saw military force as necessary to preventing rebellion by “savages.”

But, as he spent more and more time with the Stikines and other Tlingit tribes, his opinion of them slowly bettered. By the time he finished his second trip to Southeast Alaska in 1880, he had come to see these Indigenous people as admirable. He complimented them on their lack of resentment about communal living, their open acceptance of strangers like himself, their generosity and warmth.

Badly abused as a child, Muir found Tlingit parenting especially remarkable:

I never heard a cross, fault-finding word, or anything like a scolding inflicted on an Indian child…. I have never seen a child ill-used, even to the extent of an angry word. Scolding, so common a curse in civilization, is not known here at all. On the contrary, the young are fondly indulged without being spoiled. Crying is very rarely heard.

Of course, that high assessment of the Tlingits hardly fit with Muir’s earlier judgment that generational pummeling by the military was the best strategy for ensuring peace, tranquility, and assimilation. So when Muir came to pull together his journals to write Travels in Alaska at the very end of his life, more than 30 years after the fact, he deleted the long passage about collective military punishment. Likely it struck him as far too bellicose for readers in a time when war against tribal Americans was more nostalgic memory than bloody current reality. His praise of Tlingit, warmth, generosity, and parenting, however, survived the cut.

Too bad really, because Muir’s change regarding Alaska Natives is all the more remarkable when you see where he started. He had moved from endorsing military action as reasonable to embracing the Tlingits as admirable.

Which raises a big question: Did Muir apply the lessons from Tlingit country to the other tribal peoples he encountered? More about that in an upcoming Substack.

On this date …

This past Sunday, June 2, was the 100th anniversary of the U.S. law that, finally, made America's Indigenous peoples citizens. It comes as a surprise to many to discover that the first Americans weren’t Americans under the law until 1924. For an excellent telling of this story, and what more had to be done beyond citizenship to ensure legal equality for tribal Americans, check out this Substack post from Heather Cox Richardson.

Still time to enroll in tomorrow’s Cast out of Eden class

On Friday, June 7, 10–noon PDT, live-streamed and recorded, I’ll be talking about the book and taking Q&A on the many issues it raises in a session sponsored by the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at Cal Berkeley. There’s still time to enroll. Please join me!