Killing Them Softly

Only a minority of the Native Californians destroyed in the 19th century fell to gunshot, knife, or hatchet. Genocide has less ghoulish ways to wreak its lethal harm.

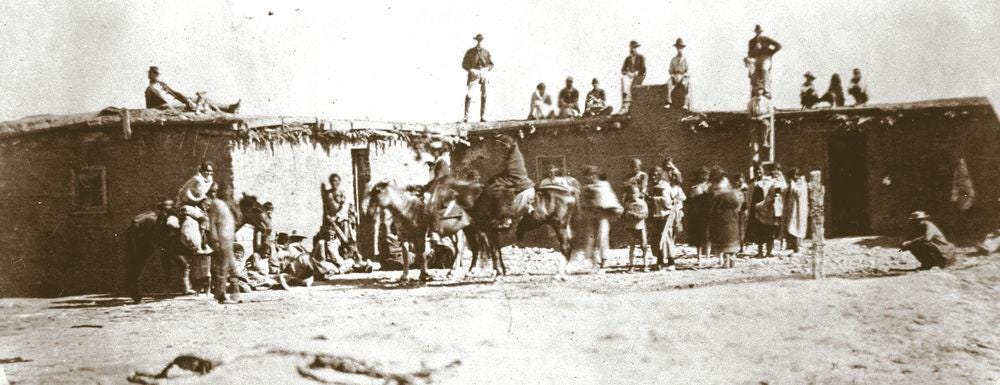

In deciding how to rid Germany and Europe of racial undesirables, Adolf Hitler drew strategic inspiration from the United States’ campaigns against the western tribes. Take the Long Walk of the Navajo (Diné) as a case in point. Following their defeat in the mid-1860s, 9,000 to 10,000 Dinés were force-marched over 300 miles from northeastern Arizona to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico. The site was less reservation than open-air concentration camp, with brackish water, little firewood, and miserable agricultural conditions. Provided with practically no food or building materials, Dinés succumbed day after day to starvation, exposure, and both infectious and chronic disease. By the time they were allowed to return to their homeland several years later, 3,500 had died.

Hitler loved it. About one-third of the Diné population had been killed off without firing a shot, showing that loss of homeland, long marches, and miserable living conditions were a bargain-basement way to dispatch the unwanted.

Whether Hitler knew it or not, a similar pattern holds for big-picture mortality in California’s genocide. Between the United States’ seizure of control in 1846 and the end of the Modoc War in 1873, the Native Californian population fell from 150,000 to 30,000. And the dying didn’t stop there. Even after the active phase of military, militia, and vigilante killing wound down in the 1870s, the dying continued. By 1900 only 15,000 Native Californians remained. In statistical terms, California’s tribal population had decreased to just 10% of what it had been, a loss of 135,000.

In his American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873, UCLA historian Benjamin Madley recounts and totals year by grim year the violence that consumed the state. According to his detailed accounting, the U.S. Army, state-funded militias, and local vigilante posses shot, knifed, or hacked to death somewhere between 12,600 and 22,000 Native Californians. That leaves 113,000 to 122,400 dead unaccounted for. What happened to them?

A lot of things, none of them pretty. Consider the convict leasing permitted under state laws patterned after the Black Codes of the pre–Civil War South. A landowner could visit the local jail, pay the fines of tribal people arrested for nothing more criminal than “loitering,” and require them to work off the debt.

Growers, most notably vineyards and wineries around Los Angeles, turned convict leasing into serial involuntary servitude. Farmhands were paid on Saturday night in aguardiente, a potent brandy. The resulting nocturnal merry-making invited raids by the sheriff and his deputies, who arrested Native Californians by the dozens and locked them up. Growers came by the county jail on Sunday, paid the fines, and assembled their convict work crews for the upcoming week. Come next Saturday, the cycle repeated.

Horace Bell, an early American Angeleno who later became a lawyer and newspaperman defending the poor, knew what he was seeing. He reported:

Los Angeles had its slave mart, as well as Constantinople and New Orleans — only the slave at Los Angeles was sold fifty-two times a year as long as he lived, which generally did not exceed one, two, or three years under the new dispensation.

The system was deadly. “These thousands of honest, useful people were absolutely destroyed in this way,” Bell lamented.

Pushed off their hunting, fishing, and gathering grounds by the gold rush and the killing campaigns that followed, tribal peoples who had once sustained themselves abundantly now faced malnutrition and starvation. The loss of homelands, with all the spiritual and cultural connections they embodied, triggered such diseases of despair as depression, alcoholism, and suicide. Infectious illnesses flourished as well, not because Native Californians were constitutionally vulnerable to invading microbes but because — as the COVID pandemic’s disproportionate effects made clear — contagious disease cuts deepest along a society’s cultural and economic fault lines to afflict the poor and the marginal.

In California no one was poorer and or more marginal than the state’s Native peoples. Everything that could kill them did and at such a scale that, in only a little more than a half-century, 9 out of 10 Native people disappeared from California with precious little fuss and less public expense.

Hitler himself couldn’t have planned it better.

Award-winning podcaster Tom Wilmer interviews me about Cast out of Eden

A seven-time winner of the Lowell Thomas Award for travel journalism, Wilmer hosts his “Journeys of Discovery” podcast on National Public Radio. Listen, for free, to our conversation about John Muir’s dark side here.

Robert, thanks for sharing this. Especially this one: "A landowner could visit the local jail, pay the fines of tribal people arrested for nothing more criminal than “loitering,” and require them to work off the debt." I think this is the part that is really stirring. I appreciate the clarity and upfront-ness of this insight. Often in history, there is really no use hiding unimaginable atrocities. Humanity must learn from their mistakes, to your point.