“No Right Place in the Landscape”

What began as a chance run-in turned into John Muir’s definitive pronouncement on dispossessing tribal people from wild lands

It was a story Muir told in print five times over, one that affected him so deeply he kept returning to it. Each time details changed, yet at its core the tale, and its implications for America’s iconic wild spaces, remained the same.

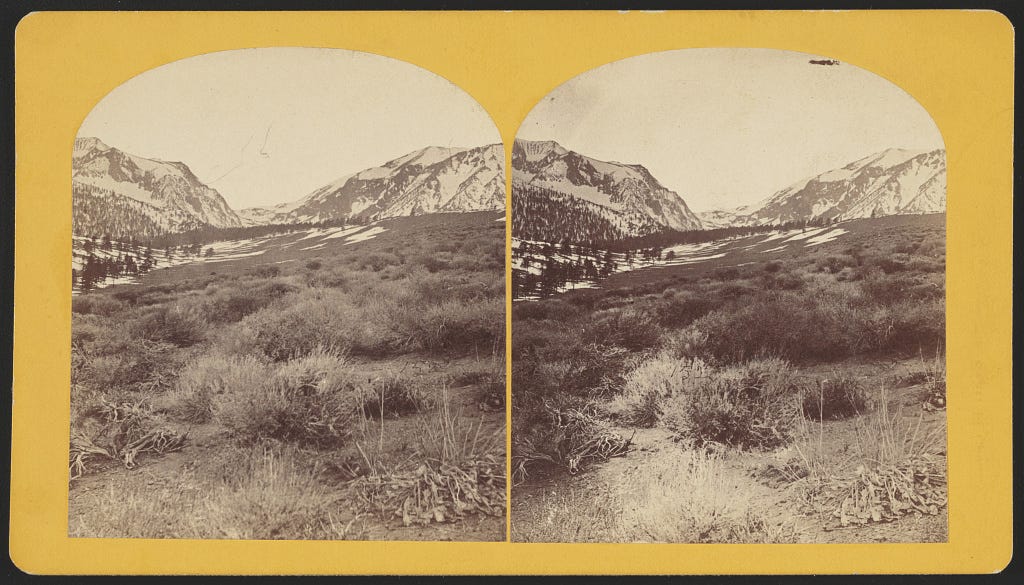

The incident that prompted this repeated retelling occurred during the summer of 1869, Muir’s first in the Sierra Nevada. Looking for a break from his sheep-herding job in the Yosemite high country, he took a couple days off to descend Bloody Canyon to Mono Lake, a famously steep and scenic descent. On the way down the narrow defile he bumped into a group of Kutzadika’as heading up. Their out-of-nowhere appearance so startled Muir that he thought them other than human:

Suddenly a drove of beings, hairy and gray, came in sight, progressing with a boneless wallowing motion, like bears.

Muir found the people he called Monos “mostly ugly, and some altogether hideous,” as well as unspeakably filthy in their rabbit-pelt clothes. They could not pass by too quickly for the endlessly fastidious Muir:

Viewed at a little distance, they formed mere dirt-specks in the landscape, and I was glad to see them fade out of sight.

When night came and Muir bedded down, his anxiety rose anew: “I experienced a feeling of uncomfortable nearness to the furred Monos,” who were camping too close for comfort. He passed “a whole night … full of strange voices, and I gladly welcomed the purple morning” to make an escape.

Muir’s mood had calmed enough by the time he reached the lake shore that he paused to watch Kutzadika’a women harvesting wild rye. They were having a good time: “their incessant laugh and chatter expressed their heedless joy.” The scene reminded him of the well-known song by Robert Burns, poet and fellow Scot, titled “Comin’ Thro’ the Rye.”

Just before he set out for Alaska in 1879, Muir recounted the incident for the second time. This telling began much the same way as the original, except that the Kutzadika’as, who knew little English, hit Muir up for whisky and tobacco and refused to believe he had none to share. These people of the second version were just as dirty as the first time around, and Muir was again happy for them to keep on going and disappear into “mere dirt specks in the landscape.” When night fell, Muir was once more unsettled by the nearness of the “furred Monos,” and he “welcomed the morning.” Again he tarried by the lake shore to watch the Kutzadika’a women at their joyous harvest “coming through the rye.”

Nine years later, he told the tale for a third time. In this version Muir decided that the offending Kutzadika’as weren’t simply disappearing dirt specks. Rather, he declared, they “had no right place in the landscape.”

After encountering the women gathering wild rye, he went on to describe the tribe’s village of “fragile willow huts … broken and abandoned.” Family groups were

… seen lying at their ease, pictures of thoughtless contentment, their wild animal eyes glowering at you as you pass, their black shocks of hair perchance bedecked with red castellias and their bent, bulky stomachs filled with no white man knows what.

The Kutzadika’as, Muir reported as if this reality were unbelievable, had a taste for insect larvae washed up by wave action in Mono Lake:

This ‘diet of worms’ is further enriched by a large, fat caterpillar, a species of silk-worm found on the yellow pines to the south of the lake; and as they also gather the seeds of this pine, they get a double crop from it — meat and bread from the same tree.

Another fifteen years further on, he detailed the Bloody Canyon story yet again. This account follows the previous one almost word for word. The Kutzadika’as were pelt-covered and dirty, they begged for whisky and tobacco, and their presence proved so disquieting that Muir had trouble sleeping. He couldn’t wait to see them gone:

Somehow they seemed to have no right place in the landscape, and I was glad to see them fading out of sight down the pass.

The fifth and final telling appeared close to the end of Muir’s life, when he was 73 years old. The Kutzadika’as were as boneless and wallowing as before, and every bit as filthy: “the dirt on some of the faces seemed almost old enough and thick enough to have a geological significance.” Again the Monos encircled him to beg whisky and tobacco until he convinced them he had nothing to offer: “how glad I was to get away from the gray, grim crowd and see them vanish down the trail!”

But this time, instead of passing a fitful night of dread at the Kutzadika’as’ closeness, Muir reflected on the meanness of his response. “To prefer the society of squirrels and woodchucks to that of our own species must surely be unnatural,” he told himself. Then he sauntered off, wishing the Kutzadika’as godspeed and summoning these famously compassionate lines from Burns:

It’s coming yet, for a’ that,

That man to man, the warld o’er,

Shall brothers be for a’ that.

Muir’s warm and fuzzy feeling soon cooled and coarsened, however. After he descended the canyon and emerged onto the valley floor, he once again stopped to watch Kutzadika’a women gathering wild rye. They bent large handfuls of the ripe grass over, beat the grains free from the stalks, and fanned them in the wind to separate the chaff:

A fine squirrelish employment this wild grain gathering seems, and the women were evidently enjoying it, laughing and chattering and looking almost natural.

Muir’s emphasis on the word “almost” underscored the bottom-line point he sought to make:

Most Indians I have seen are not a whit more natural in their lives than we civilized whites. Perhaps if I knew them better I should like them better. The worst thing about them is their uncleanliness. Nothing truly wild is unclean.

Muir kept going, at pains to further depict the Kutzadika’as unnatural. They lived, after all, in “mere brush tents where they lie and eat at their ease,” made their women pack unchivalrously heavy loads over the Sierra Nevada, and relished insects as food, subsisting “chiefly on the fat larvae of a fly that breeds in the salt water of the lake, or on the big fat corrugated caterpillars of a species of silkworm that feeds on the leaves of the yellow pine.” Indeed, of all the foods offered by the Kutzadika’as’ home range, “strange to say, they seem to like the lake larvae best of all,” he reported.

Muir’s dietary squeamishness stands out, for, like all Scots, Muir knew his native land’s national dish to be haggis. It is a singular concoction: sheep’s stomach stuffed with chopped animal offal, oatmeal, suet, and spices then boiled. Haggis takes more than a little getting used to — the traditional glass of Scotch whiskey on the side helps — yet it is so quintessentially Scottish that Burns addressed a praise poem to the dish as “Great Chieftain of the Puddin’-race.” Muir could have recognized that Kutzadika’as relishing insect larvae were hardly stranger than Scots savoring haggis, but no. He painted them as neither natural nor civilized, pushing them outside the bounds of Burns’s worldwide brotherhood. The Kutzadika’as were irredeemably other, a people “with no right place in the landscape” properly dispossessed from otherwise pristine spaces.

Up next: Trump, Denali/McKinley, and the Name-Change Game.