Playing the Newbie

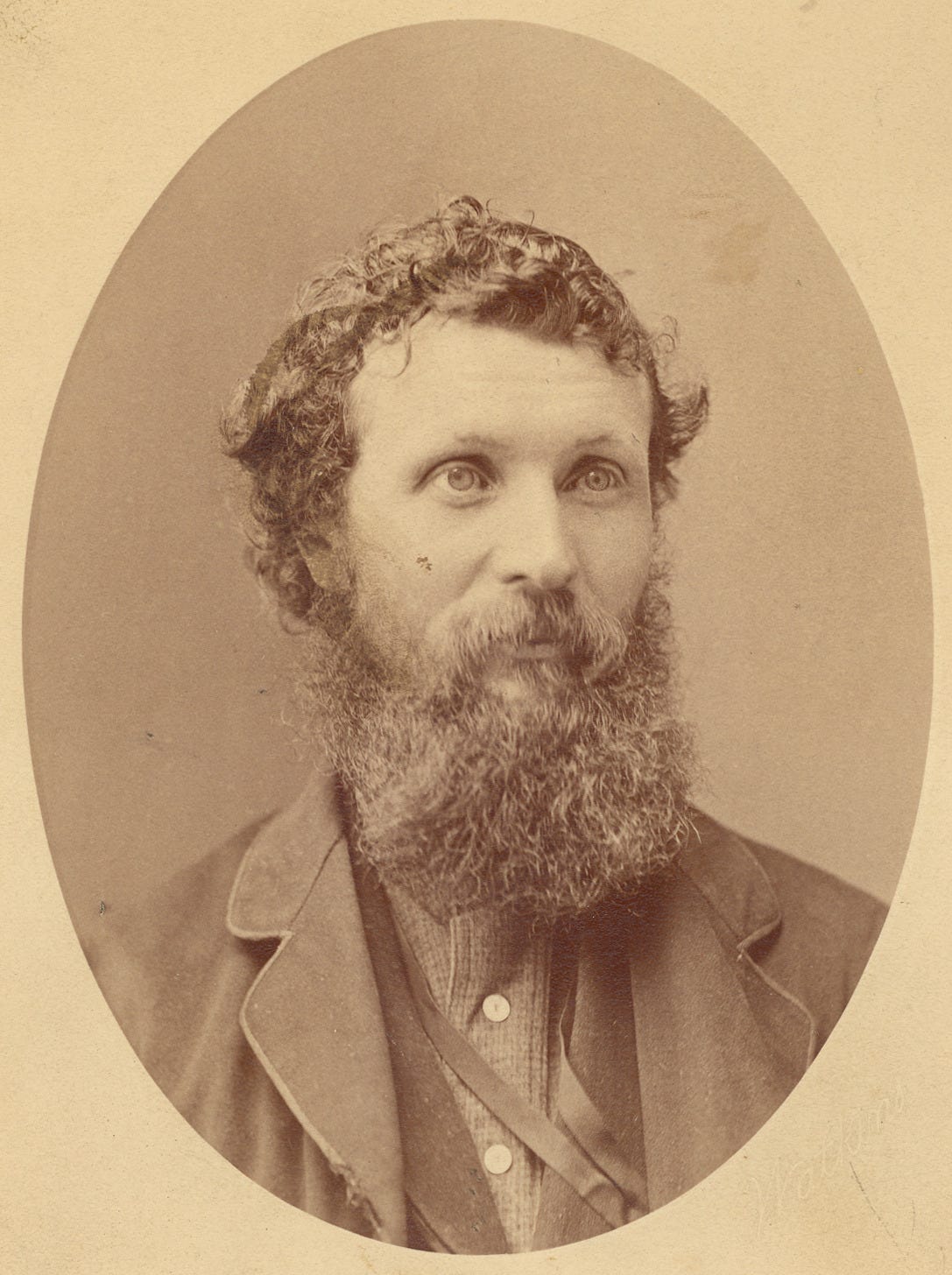

John Muir posed as a wilderness superhero. A young journalist bought the act.

It was a tough time for Muir. His younger daughter, Helen, had been hit with recurring bouts of pneumonia that prompted him — ever the devoted father — to move himself and both daughters from Northern California to the Arizona desert, hoping for a cure in the dry air. While they were away, wife and mother Louie took gravely ill, prompting Muir and elder daughter Wanda to return to Martinez. Louie worsened and died in June 1905. Too sick to travel, Helen remained in Arizona, and through the following months Wanda and John spelled each other in staying with her.

On a train back to California in spring 1906, Muir fell into conversation with a young man who was excited to learn just who this bearded elder was. After all, the wild prophet on the train had camped with no less a figure than then-President Teddy Roosevelt in Yosemite and was making quite the name for himself as an advocate for national parks and wild lands.

The eager young man was E. French Strother, who worked for book publisher Doubleday and its pro-business magazine The World’s Work. Strother smelled an editor-pleasing story in this serendipitous encounter. So did Muir, but to a purpose different from Strother’s. Ever the wry Scot, Muir spun an impossibly tall tale, likely to see whether Strother would buy it. And did he ever.

This bit of wink-wink myth-making turned on Muir’s first climb to the peak of Mount Shasta, in November 1874. It was, he told Strother, something of an impetuous lark. Leaving Sisson’s Hotel near the foot of the mountain and telling Mrs. Sisson he’d likely be back by lunch, Muir climbed up to the timberline before the sun went down. He camped without food or blankets, then took off for the summit in the morning.

Caught in a sudden snowstorm on his way down from the summit, Muir sought refuge in the lee of a downed tree and kindled a fire as darkness fell and snow blew fiercely. He was warm enough, but he had nothing to eat. By the time the storm relented, two days had passed since Muir’s last meal:

I've often spent two days without anything to eat and even felt better for it; but the third day is getting toward the point of being too much.

Muir left his bivouac and descended through the snowy timber. He was, he told Strother, heading toward smoke rising from a campfire where several Mexican sheepherders had pitched tents. Muir, who spoke no Spanish, let the sheepherders know by gesture and signal that he was so, so hungry. Hospitably they fed this famished gringo, and he hung around, leaving the next morning with a sack of bread and ground coffee over his shoulder. Muir had decided he wasn’t heading back to Sisson’s. No, he was going to circle Shasta itself.

That circumnavigation was quite the saunter, as Muir told Strother:

On the seventh day I completed the circuit of the mountain, and about noon I sauntered up the walk to Sisson’s, as if I had just come in from a half-hour's stroll. Mrs. Sisson saw me and called out, “Well, Mr. Muir, do you call this a short walk? Where have you been? I’ve had a guide out searching for you.”

“Oh, I just took a little walk: I went around the base of the mountain. But I got back in time for lunch, didn’t I?”

I had been gone seven days and had walked a hundred and twenty miles.

Strother took down everything Muir said as fact, and the great seven-day, 120-mile trek around Shasta fueled by borrowed bread and coffee made it into the young writer’s unbylined profile that ran in the November 1906 World’s Work. Had Strother bothered to check the facts, he would have soon seen that Muir was playing him.

For one thing, the details didn’t add up. Muir made the climb in November, unusually late in the year not only for climbers seeking the summit but also for sheepherders to be grazing their animals the mountain. So that detail stood out as strange. And if Muir actually walked 120 miles in the four days after his encounter with the sheepherders, he would have had to do 30 miles per day, a hellishly hot pace in the absence of trails, particularly in a blizzard’s aftermath. An experienced mountaineer can circumnavigate Shasta’s peak close to timber line, but the distance is about 35 miles, not 120, and it entails arduous scrambles down and up deep glacial-stream canyons slick and slippery with scree. Thirty miles a day? Not a chance.

Strother had fallen into the journalist’s trap of writing a single-source story, which always carries with it the danger of being taken in. To check the facts, the journalist should have turned to a reliable second source: Muir’s own younger self.

The mountaineer summited Shasta during his 1874 walk to northeast California on a reporting assignment for San Francisco’s Daily Evening Bulletin. The climb centered a long story entitled “Shasta in Winter” that ran about a month after Muir topped the summit. It bears little resemblance to the tale he spun for Strother’s naïve benefit.

As Muir reported:

The ordinary and proper way to ascend Shasta is to ride from Sisson's to the upper edge of the timber line — a distance of some eight or ten miles — the first day, and camp, and rising early push on to the summit, and return the second day. But the deep snow prevented the horses from reaching the camping-ground, and after stumbling and wallowing in the drifts and lava blocks we were glad to camp as best we could, some eight or ten hundred feet lower. A pitch-pine fire speedily changed the climate and shed a blaze of light on the wild lava slope and the straggling storm-bent pines around us. Melted snow answered for coffee-water and we had plenty of delicious venison to roast.

Come the early hours of the morning, the venison-stoked Muir slogged his way to the summit. Although a blizzard caught him on the way down, he made it back to base camp, where food, blankets, firewood, and a wind-proof shelter in the lee of a block of red lava awaited. Muir nested up, warm and full and out of the icy blast until the third day, when a concerned Justin Sisson dispatched a wrangler with two horses to fetch him back. The rescue irritated Muir: “I had expressed a wish to be let alone in case it stormed.” Still, he headed down, pleased in the end for a warm place by the hotel fire to watch the remainder of what proved to be a week of back-to-back storms.

It’s a very different story: no impetuous saunter to the summit, no two-day fast, no 120-mile four-day circuit of the mountain, no flippant boast to Mrs. Sisson. Yet that’s the story Strother ran in The World’s Work without the least fact check.

When the wilderness elder read it, his wry inner Scot must have chuckled at how easy it had been. As for Strother, his story actually advanced his career. More about that soon.

Sources and methods

Strother’s story in The World’s Work and Muir’s own in the Daily Evening Bulletin are well worth reading just to see how differently they read and what that difference says about Muir in each instance.