Something Muir and I Share: Big 10 Educations Endowed by Tribal Land

Take a guess: How did the acreage offered to land-grant universities under the Morrill Act become the federal government’s to give away?

When we last visited the young John Muir in Wisconsin, he had barely survived suffocation in a well bore and resolved to escape the family farm. It wasn’t the wild that got him out, though. It was his love of tinkering and inventing.

Determined to pursue the poetic delights of Shakespeare and Milton and to invent the next big thing, Muir cut his sleep to only five hours a night and rose early both to read and to tinker. His first creation was a self-setting sawmill, then a series of:

waterwheels, curious door locks and latches, thermometers, hygrometers, pyrometers, clocks, a barometer, an automatic contrivance for feeding the horses at any required hour, a lamplighter and a fire-lighter, an early-or-late rising machine, and so forth.

Muir’s inventions impressed the neighbors, who pronounced him a genius sure to rise in the world. One nearby settler encouraged Muir to exhibit his work at the upcoming state fair; surely his clever machines would earn him a good-paying job in a machine shop. Bucked up and determined, Muir headed off for Madison, Wisconsin’s capital, with two clocks and a small thermometer fashioned from hickory under his inventive arm, and put them on exhibit in the fair’s Temple of Arts building. There this farm boy turned inventor won raves in the press and a cash prize.

He also won that machine shop job where he traded work for meals and devoted his free time to studying science. But when he made little headway in self-education, Muir headed back to Madison, hoping to enter the University of Wisconsin:

I was desperately hungry and thirsty for knowledge and willing to endure anything to get it.

Muir’s palpable desire proved persuasive. Although he had had no formal schooling since Scotland, he talked the acting president of the university into admitting him into the preparatory department — essentially a fast-track, remedial high school. Muir advanced to the university as a freshman in February 1861, just as the United States was tumbling toward the chaos of the Civil War.

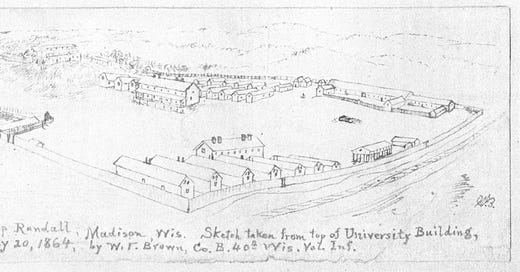

The outbreak of war two months later changed Madison and the university suddenly and dramatically. The state fair grounds where Muir had exhibited his inventions turned into an army training center named Camp Randall. Some 70,000 recruits passed through the camp on their way to the battlefield over the course of the conflict. Sex workers and liquor sellers took every possible advantage of the displaced, bored, and horny young men.

Muir, disturbed by the camp’s licentious atmosphere, visited recruits he knew back home and urged them to hold to the straight, narrow, and evangelically Christian. Camp Randall showed him, too, direct evidence of war’s horrors. Approximately 1,200 Confederate prisoners of war were held at the camp under such bad conditions that 140 of them died. Muir witnessed their suffering in the camp hospital and briefly considered heading off to medical school.

The Civil War had another effect on Madison: it threatened the university’s existence. The flood of Wisconsin military enlistees drained the pool from which the university recruited its students. As enrollment fell, so did the university’s revenue.

The situation looked threatening. In a letter to his sister Muir wrote:

Our University has reached a crisis in its history, and if not passed successfully, the doors will be closed, when of course I should have to leave Madison for some institution that has not yet been wounded by our war-demon.

Fortunately for him, Muir remained in school. Financial rescue did come — from expropriated Native American land.

The Morrill Act, also known as the Agricultural College Act, was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862, Muir’s second academic year in Madison. It promised each state between 90,000 and 990,00 acres, based on the size of its congressional delegation, as long as the state agreed to conserve and invest the principal raised from the land grant and to establish a university-level agriculture department. In the end, 52 public institutions benefited from this giveaway and are known as land grant universities.

What the law did not say was that the land to be distributed — nearly 11 million acres in total, an area larger than all of Maryland or two-thirds of West Virginia — had been taken from tribal nations under coercion, armed force, and dubious treaty. The state of Wisconsin accepted its Morrill grant of 235,530 acres of formerly Ojibwe and Menominee land in 1863, and in 1866 designated the University of Wisconsin as beneficiary of what became a $303,349 endowment.

In today’s economy of millions, billions, and trillions, that number sounds paltry. But at a time when the university was small and the student body numbered only in the dozens, those funds proved critical to keeping professors teaching and students studying.

The Morrill Act wasn’t the only source of expropriated tribal land that benefitted the university. Earlier the state of Wisconsin had taken possession of 3 million tribal acres under the Swamp Land Act of 1850. In 1865, just as the full benefit of the Morrill Act was becoming clear, the state sold off 1.5 million acres and invested the proceeds in the Normal School Fund to benefit Wisconsin’s public educational system. Today the trust fund totals $30 million, and income continues from timber harvesting on the 70,000 acres still under the state’s control as well as from interest on the principal. In 2023 the fund sent more than $1 million to Wisconsin schools.

Like the “frontier” created by forcing Indigenous people off their homelands, the free land the University of Wisconsin received from the federal government was taken to the profit of Euro-Americans and the loss of Native Americans. That was how settler colonialism worked, and it kept John Muir in school.

He wasn’t the only one. My own education culminated in degrees from two Morrill Act recipients, The Ohio State University — like the University of Wisconsin a Big 10 school and the recipient of more than twice as much tribal land as Wisconsin — and the University of California, Berkeley. Long, long after the wars that pushed the tribes to the edge and took their land, I benefited from that theft as had John Muir.

Proof yet again that settler colonialism isn’t something that happened way back when and stopped. Even now it continues to work its harm.

Links & Leads

• In 2020 High Country News published a stunningly detailed investigation on just how extensive Morrill Act land expropriations were and how they continue to pay off for schools the article dubs “land grab universities.”

• After Tristan Ahtone (Kiowa), one of the investigation’s authors, moved to Grist, that magazine picked up the baton and showed how some Morrill Act holdings contribute to climate change.

• Wisconsin’s ongoing profit from the legacy of expropriated tribal land become clear in this recent feature in the Wisconsin Examiner.

• Ohio State is beginning to come to terms with the violent origins of its founding endowment and working toward a restorative recognition of the debt it owes the state’s tribes. There’s a lot of work to be done.

• Cal Berkeley is following a similar path, based on a 2021 report entitled The University of California Land Grab: A Legacy of Profit from Indigenous Land. Here, too, the work is immense.

Cast out of Eden Comes to Zoom

This Saturday, April 27, 2 p.m. PDT, I’ll be talking and taking Q&A on the book with the Ina Coolbrith Circle, a Bay Area writers group. Open to all, free, and Zoom only. Please join me!