The Company He Kept: John Muir’s Slave-Owning Soul Friend, Part 1

Two elements brought Joseph C. LeConte and Muir together for life: light and ice.

Although environmentalism sits squarely on the progressive left these days, it didn’t start out there. In fact, the roots of the American conservation and preservation movement reach deep into the political right wing. Over the next few weeks CAST OUT OF EDEN will offer close-ups of the white supremacists connected to John Muir who worked alongside him to save wild mountains.

The light that connected LeConte and Muir came soon after the two had taken off together into the Yosemite high country for the first time. Following supper and a chat around the campfire at Tenaya Lake, the two men sauntered through a pine grove and perched on a rock reaching out into the water. Bathed in a full moon under the high-altitude vault of sparkling summer stars, the mountains around them glowed, their illuminated forms dancing in what Muir called the water’s “unstable mirror.” The two chatted then fell silent as “earth and sky were inseparably blended and spiritualized, and we could only gaze on the celestial vision in devout, silent, wondering admiration.” LeConte, too, was moved. The “grand harmony made answering music in our hearts,” he recalled. The two new friends contemplated side by side for a silent hour.

That experience of awe shared beyond words captured Muir’s lifelong reverence for LeConte. As he told a memorial gathering after his friend’s death almost 30 years later:

The lake with its mountains and stars, pure, serene, transparent, its boundaries lost in fullness of light, is to me an emblem of the soul of our friend.

The ice had to do with glaciers. Long saunters through the High Sierra convinced Muir that glacial forces had played a huge hand in shaping the range’s peaks and valleys, living glaciers still plowed the alpine heights, and Yosemite Valley itself resulted from massive glacial sculpting. As the two explored the high country, Muir pointed out moraines, grooves, and polishing from glaciers long gone so impressively that LeConte was persuaded.

Not everyone was of the same mind. Josiah Whitney, California’s most prominent scientist at the time, dismissed Muir’s ideas, published soon after his meeting with LeConte, as campfire science. He knew full well that the Sierra Nevada showed evidence of glaciation, but the idea that slow-moving ice had carved out Yosemite Valley struck him as ludicrously over the top. The valley had formed, he was sure, from massive subsidence, a catastrophic downward slip of rock strata.

Time was to prove Muir and LeConte right, Whitney wrong. Yet that success was not what bound the two friends together. Their connection formed at a level well below the thin air of academic theory, the one revealed by their quiet hour at Tenaya Lake and what led up to it.

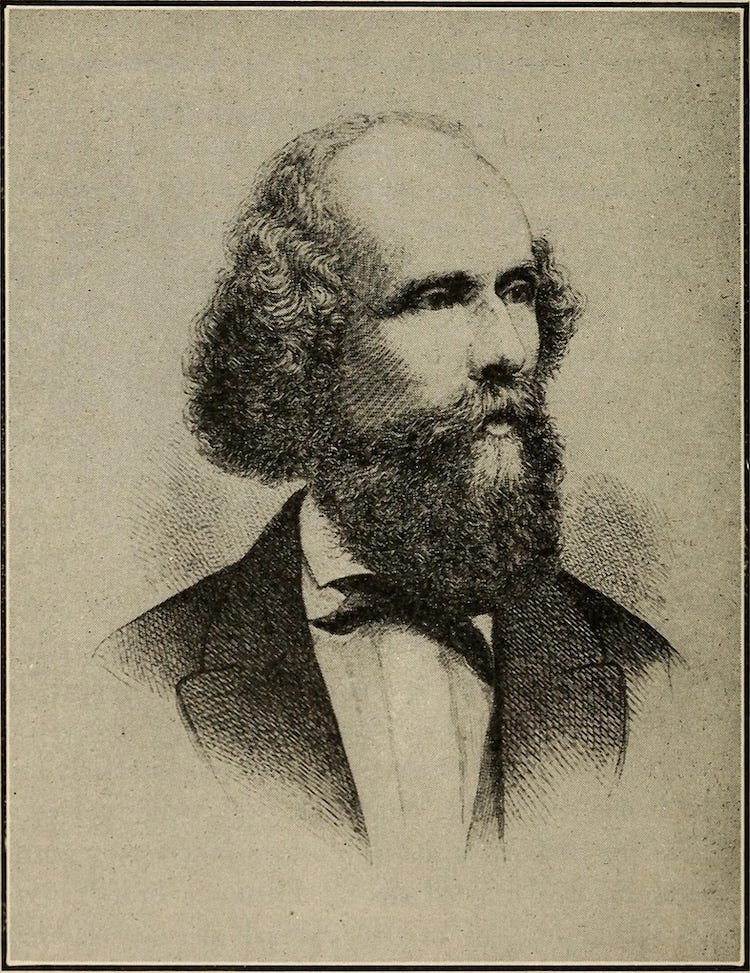

A professor at the University of California, LeConte was planning to lead a student group into the High Sierra, and a mutual friend arranged for him to meet Muir in Yosemite Valley. Recognizing Muir as “a gentleman of rare intelligence, of much knowledge of science, particularly botany,” LeConte proposed that Muir come along on the field trip. Ever eager to get away into the high country, Muir accepted.

LeConte’s backcountry manner soon convinced Muir that he had found a worthy companion:

Sinewy, slender, erect, he studied the grand show, forgetting all else, riding with loose, dangling reins, allowing his horse to go as it liked. He had a fine poetic appreciation of nature, and never tired of gazing at the noble forests and gardens, lakes and meadows, mountains and streams.

LeConte came to the Yosemite trek trailing a considerable backstory. Born in 1823, he grew up on a large plantation in Georgia’s coastal lowlands. This was a happy world, LeConte made clear, owing to his father’s “just, wise, and kindly management of his two hundred slaves.” Just to be sure the slaves stayed in line, his father joined other planters to form a mounted police force that chased down Blacks abroad at night without passes — something of a Ku Klux Klan on training wheels. The pairing of wisdom and whip was salutary, LeConte argued:

There never was a more orderly, nor apparently a happier, working class than the negroes [sic] of Liberty County as I knew them in my boyhood.

Spending much of his boyhood hunting and fishing, LeConte was drawn to study natural history and science. After college, he entered New York City’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, now the medical school of Columbia University. Little interested in practicing medicine, he saw a medical degree as “the best preparation for science.” He did practice back home for two and a half years, then, upon learning that famed Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz had been appointed to a Harvard professorship, headed there to advance his studies. LeConte worked at Agassiz’s side, absorbed science under his fierce mentorship, and took in his long, philosophical monologues. LeConte recalled:

To explain how much I owe to him, it is only necessary to say that for fifteen months I was associated with him in the most intimate personal way, from eight to ten hours a day, and every day, usually including Sundays.

The third lesson, built on Agassiz’s evolutionary theory, was what LeConte called scientific sociology. It depicted society as “an organized body, and therefore subject to the laws of organisms. Society, too, passes by evolution from lower to higher, from simpler to more complex, from general to special, by a process of successive differentiation.” Humankind begins in barbarism and evolves into civilization.

Agassiz expanded this thinking into a theory of race while LeConte was his student. Before coming to America, the Swiss scientist held that all humans originated from one creation, just as Genesis recounts. Whatever the differences among various groups of humans, all were one species under the skin. But Agassiz’s first experiences with African Americans shocked him into rethinking this belief. As he wrote home to his mother in Switzerland:

It is impossible for me to repress the feeling that they are not of the same blood as us. In seeing their black faces with their thick lips and grimacing teeth, the wool on their heads, their bent knees, their elongated hands, their large curved nails, and especially the livid color of their palms, I could not take my eyes off theirs face in order to tell them to stay far away.

Driven by repulsion and holding to his view of species as immutable thoughts in the Creator’s mind, Agassiz argued more and more forcefully that each human race — Caucasian, Arctic, Mongol, American Indian, Negro, Hottentot, Malay, and Australian by his accounting — resulted from a separate creation and was a distinct, immutable species. Holding to any other position, Genesis not withstanding, was “contrary to all the modern results of science,” he declared.

LeConte drew deeply from Agassiz’s mentorship throughout his own long scientific career. Agassiz on ice helped prepare his mind to welcome Muir’s hypothesis on the glacial origin of Yosemite Valley. And the Swiss scientist’s thinking on evolution and society, shaped by unmitigated racism, gave a “scientific” cant to how LeConte, the son of slaveholders, would address the same deeply American issues in the hard days following the Civil War.

Next up: John Muir’s Slave-Owning Soul Friend, Part 2

New tribal national monuments proposed

At the 16th United Nations Conference on Biological Diversity in Cali, Colombia, last week, the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe and the Pit River Tribe called upon the Biden administration to protect as three national monuments some 1 million acres of sacred and sensitive lands in California: Kw’tsán National Monument, Chuckwalla National Monument, and Sáttítla National Monument.

You can help in this worthy effort by signing the petitions on the proposed monuments’ websites and asking your friends, neighbors, and social media contacts to add their names as well. Every signature increases the public pressure to get this done before Trump 47 renews his war on the earth and its Indigenous peoples.

Cast out of Eden on radio next Tuesday

On Nov. 19 at 8:30 a.m. Pacific Time, “This Green Earth” host Chris Cherniak will interview me about the book on KPCW, the National Public Radio affiliate in Park City, Utah. Livestream at the KPCW website or listen in via iHeartRadio.

Half off on all Native American and Indigenous studies titles

To mark Native American Heritage Month, the University of Nebraska Press is offering 50% off through Nov. 29 on its entire list of books about Indigenous America. That includes my Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age and Cast out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness as well as hundreds more titles, both scholarly and general interest. Order online and use discount code 6NAT24 at checkout.