The Company He Kept: The Aristocrat Scientist Who Named T. rex and Lauded John Muir's Inner Viking

Henry Fairfield Osborn and Muir came from starkly different backgrounds. Still, they bonded over threats to wild places and the rightful supremacy of Euro-Americans.

In the 1890s, as America grew more and more aware of its threatened wild heritage, John Muir become a star writer for The Century Magazine under brilliant editor Charles Underwood Johnson. The well-connected Johnson not only gave Muir a media outlet, but also introduced him to some of the most prominent figures of the time. People like Nikola Tesla, inventor of the alternating-current system that made widespread electrification possible; naturalist and writer John Burroughs; historian Francis Parkman of Oregon Trail fame; and writers Mark Twain, Sarah Orne Jewett, George Washington Cable, and Rudyard Kipling. Prominent even in this prominent company, and soon a close friend and ally to Muir, was Henry Fairfield Osborn.

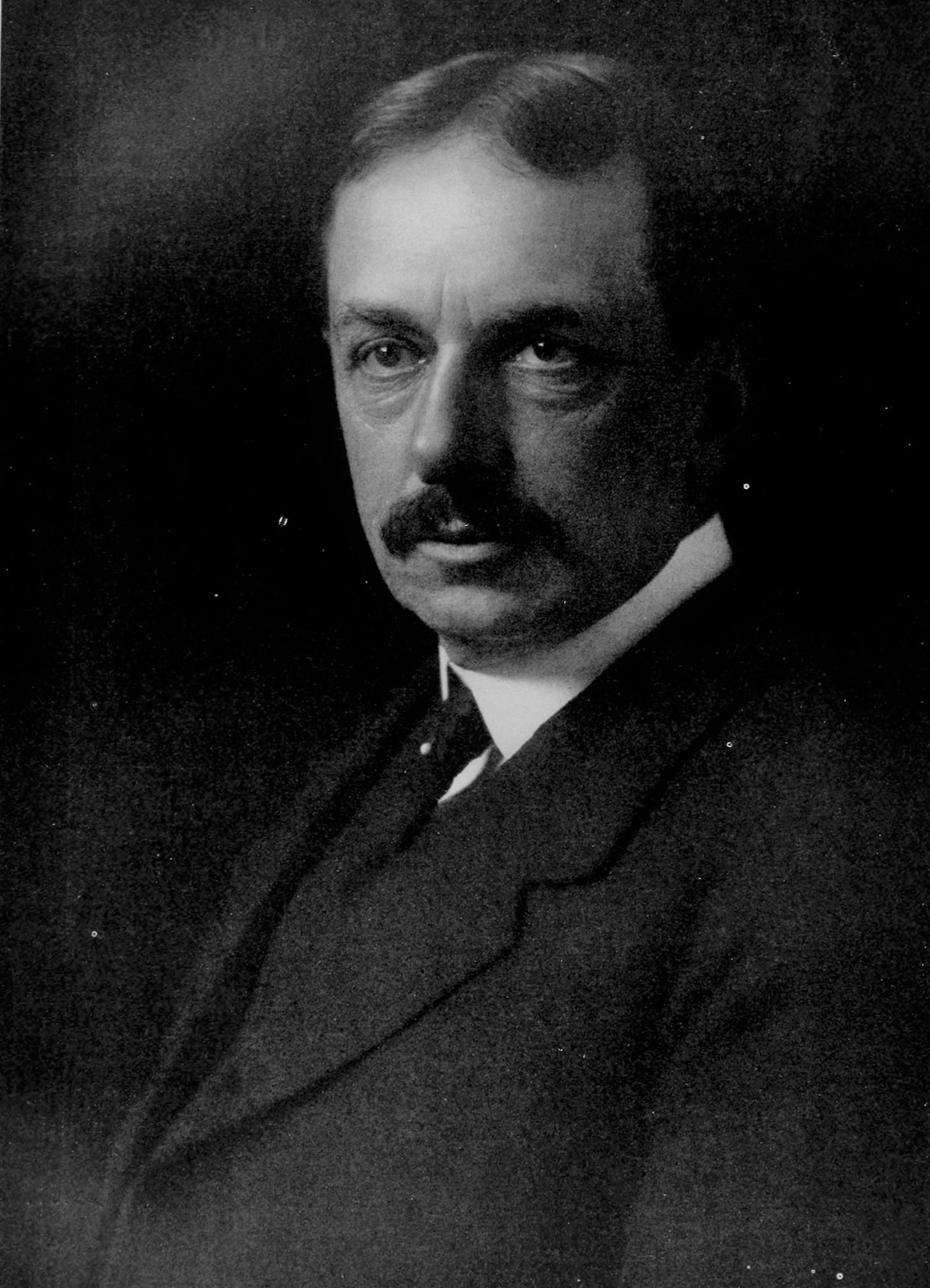

Osborn was his era’s version of public scientist on the order of today’s Jane Goodall or Neil deGrasse Tyson. Born to stunning wealth in a Connecticut family that included kingpin financier J. Pierpont Morgan, Osborn considered eminence his due. After all, he was the Princeton-trained vertebrate paleontologist who named Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor and headed the prestigious American Museum of Natural History for a quarter-century. Elected secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the highest scientific position in the country, Osborn turned the honor down. His research and leadership calendar was already too packed to take on the added responsibility that came with the accolade.

Becoming fast friends soon after they met, Osborn and Muir spent time together as often as residents on opposite sides of the continent could. Muir and the Osborn family cruised through Alaska’s Inside Passage in 1896, among other travels together. And whenever Muir was in the East, particularly after his wife died in 1905, he was a frequent house guest at Castle Rock, Osborn’s grand country manse up the Hudson River from New York City. Whenever distance separated the two, correspondence flowed between them.

Although Muir and Osborn came from different social classes and educational backgrounds, they shared similar views on science and religion. Muir saw evolution not as the bloody survival of the fittest but as the unfolding of the Divine’s loving creation. Osborn similarly understood evolution as a spiritual force joining science and religion. He wrote that “from the earliest times Nature has been regarded as the work of God, full of moral beauty, truth, and splendor.” It made sense that naturalists like Muir and himself were religious. After all, “primitive religion issues out of the heart of Nature in reverence for the powers of the unseen.” Science all by its lonesome fell short:

Here nature, religion, and beauty, kept apart by the superficial vision of man in science, theology, and aesthetics, are one in the eternal vision and purpose of the Creator.

This unity became incarnate in John Muir. The naturalist, Osborn wrote, felt deeply that “all the works of nature are directly the works of God”:

I have never known anyone whose nature-philosophy was more thoroughly theistic; at the same time he was a thorough-going evolutionist and always delighted in my own evolutionary studies, which I described to him from time to time in the course of our journeyings and conversations.

Osborn was sure that Muir’s point of view arose from both nature and nurture:

I learned through correspondence and through long and intimate conversations thoroughly to understand his Scotch soul, which had a strong Norse element in it and a moral fervor drawn from the Bible of the Covenanters.

Long years of study in field and laboratory led Osborn to claim for himself a deep “penetration into the sources of human character and personality … due to my studies in heredity and my observations on the difference in races and racial characteristics.” Race was all, for “distinctive spiritual and intellectual powers originate along lines of slow racial evolution in climate and surroundings of distinct kinds.”

Osborn divided “Homo sapiens into three absolutely distinct stocks, which in zoology would be given the rank of species, if not genera; these stocks are popularly known as the Caucasian, the Mongolian, and the Negroid.” The biological divisions among these three varieties of human were, according to Osborn, as deep-rooted and absolute as those dividing domestic dogs from foxes and jackals: “The spiritual, intellectual, moral, and physical characters which separate these three human stocks are very profound and ancient.” We humans were not all one, not by a long shot.

As Osborn saw the matter, not even all Caucasians were created equal white folks. Rather, Europe’s nations fell into three races distinguished by characteristics so stark “that if we encountered them among birds or mammals we should certainly call them species rather than races.” The most highly evolved, a race bred to conquer and rule, were the Nordics, a. k. a. Aryans: a tall, fair-haired people that included not only Scandinavians but also Anglo-Saxons, northern Germans, and Lowland Scots like Muir. Nordics were “fond of the open, curious and inquisitive about the causes of things; deliberate in spiritual development,” and “very gradually they reached the greatest intellectual heights and depths.”

Then there were the broad-headed and broad-faced Alpines, a. k. a. Celts. They arose in Central Europe, a talented race but “neither adventurous nor sea-loving.” Last and lowest came the dark-eyed Mediterraneans; think Italians, southern French, and Greeks. Great sailors and artists for sure, yet they mistook nature for God, lacked any aptitude for study and contemplation, and could never rise as high as Nordics or Alpines in conquest or intellect.

Muir’s genius turned on his being a Scot with the nature-penetrating heart of a Norse sea-rover, according to Osborn. And Muir proved to be a warrior renowned for his Viking-style “fearlessness of attack, well illustrated in his assault on the despoilers of the Hetch Hetchy Valley of the Yosemite, whom he loved to characterize as ‘thieves and robbers.’ It was a great privilege to be associated with him in this campaign.”

It only made sense for Osborn to join Muir in the years-long fight to stop the dam:

It appears that the finest races of man, like the finest races of lower animals, arose when Nature had full control, and that civilized man is upsetting the divine order of human origin and progress.

Osborn made clear what the times required:

Care for the race, even if the individual must suffer — this must be the keynote of the future.

The men Osborn recruited into the save-Hetch-Hetchy campaign shared his white-supremacist views. The most prominent, and most notorious, among them was long-time friend Madison Grant, a racist of such standing that his fan mail included a letter from a then little-known Bavarian politician named Adolf Hitler.

Next up: The Passing of the Great Race and all that.