The First Time

Labor Day weekend marks the 55th anniversary of my maiden backpack into the High Sierra. Awe was about to happen.

To be sure, I qualified as a total backcountry idiot. Picked a route off a random topo map of Yosemite National Park without realizing that the first day’s hike required a punishing, hours-long climb. I was from central Ohio, after all, where elevation counts for little, and my buddy Gene, a fellow UC Berkeley student, came from the Florida Panhandle, which is even flatter. We decided to save the cost of sleeping bags and pads by rolling up in blankets on the hard, night-cold ground. Yeah, right. For meals we carried canned chili, boxed mac and cheese, dry salami, and Snickers. The chipmunks raiding our packs at night adored the Snickers, nibbling each bar down in an ecstasy of chocolate and peanuts. As for the backpacks, they were bargain-basement rigs from a military surplus store without hip pads and waist belts, so the weight bore down on spine and shoulders and made high-altitude breathing even harder. We never gave a thought to a tent, as if rain were beyond imagination. It wasn’t.

Yet, for all that unprepared ignorance, something special happened anyway.

Not that I felt that way after the first day’s climb from Wawona, at the southern end of Yosemite, up to Chilnualna Falls, a hip-busting 2,300 feet in just over 4 miles. We had started on the trail late after driving from Berkeley, and the sun was grazing the horizon by the time we survived uncountable steep switchbacks and finally made the top. Thunder echoed to the east, threatening rain on the untented two of us. So when a ramshackle trail cabin used by park rangers on their backcountry rounds appeared close to the falls and we found the door unlocked, it felt like deliverance from all things wild and threatening.

The cabin floor proved hard and cold, and the blankets sponged up the must of the old, winter-wetted wood within minutes. Between tosses and turns my little sleep was troubled by the fear that, should the next two days prove as difficult as the first, doom was certain. Still I soldiered on, something one does at the age of 23, climbing steadily upslope through forests slowly thinning and changing with the rising altitude.

Our route passed Crescent Lake, a little to the south of the trail. Farther along at Johnson Lake we stopped to rest and snack before deciding to keep on to the next lakeside campsite. At the leading edge of the gloaming, Gene and I broke out of the last trees and beheld, in a sudden vision, what this journey was all about.

Royal Arch Lake reached in a windless sheet toward the rock face that gives the place its name. Formed of the gray granite that shapes Yosemite’s wonders, the prominence rose in dark, exfoliated waves resembling an arch. And it was gigantic, reaching hundreds upon hundreds of feet above the water to touch a sky just beginning to pink with alpenglow. Gene and I gawked at this intersection of water, stone, and sky, and took in a wordless awe unlike either of us had ever known.

Never mind that we chose, like the idiots we were, to bed down in a green meadow at lake’s edge where heavy dew drenched the blankets through by dawn. Never mind that the next day we still had to cover more than a dozen miles to return to Chilnualna Falls by evening and then head down to the trailhead the next morning to get back to Berkeley on time. Never mind that by the end of that third long day my heels bloomed into blisters the size of 50-cent pieces. All that was a small price to pay. The high country had reached inside at Royal Arch and changed me.

For decades thereafter, a highpoint of the year became backpack trips that filled summer and fall. Never did I go back to Yosemite — too many people — focusing instead on the less populated northern Sierra Nevada, particularly the Desolation Valley and Mokelumne Wildernesses. After that came Mount Lassen and the California Cascades, the Yolla Bolly Wilderness closer to the coast, then, and most wondrously, the Trinity Alps. On every trip, if only for a few sudden seconds, the awe first bestowed at Royal Arch Lake came back. And it just got better with age.

John Muir, too, experienced such awe; it changed him as well. “Never shall I forget my baptism in this font,” he wrote. Perched on a summit in Twenty-Hill Hollow in the Sierra foothills, Muir watched his miracle unfold:

The Hollow overflowed with light, as a fountain, and only small, sunless nooks were kept for mosseries and ferneries…. Light, of unspeakable richness, was brooding the flowers. Truly, said I, is California the Golden State — in metallic gold, in sun gold, in plant gold. Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence; you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.

Muir thought that this expanded awareness was available only to people like himself, white Anglo-Saxon Protestants willing to dare the granitic heights, those with souls big enough to expand into nature’s core. Good Calvinist that he was, he saw the soul as an individual possession, like skin color or IQ, and the experience of awe as the personal achievement only of the righteous.

But what if awe actually works the other way around? What if we don’t reach out, but nature reaches in? What if soul isn’t ours but the world’s and its embrace animates everyone, not only the few and select?

Chickasaw poet, novelist, and essayist Linda Hogan sees it this way:

For the Native mind, the world creates and gives birth to us and our spirits, along with all the rest. The soul resides in the world around us; it shares itself with us. We breathe its breath. We are blessed by its light.

My soul didn’t reach out into the cosmos at Royal Arch Lake, nor did Muir’s on that hilltop in the hollow. Rather, the cosmos’s deepest being breathed itself into both of us and filled us with awe at its presence. Surely no wild blessing is greater.

Project 2025 where the wild things are

The far right’s wish list for governmental overthrow under a second Trump administration goes beyond the downfall of the Antiquities Act I warned about last week. It entails a broad assault on long-standing environmental regulations, endangered-species protections, and the very notion of public land. Read all about the potential horror in this Sierra online feature by Lindsey Botts.

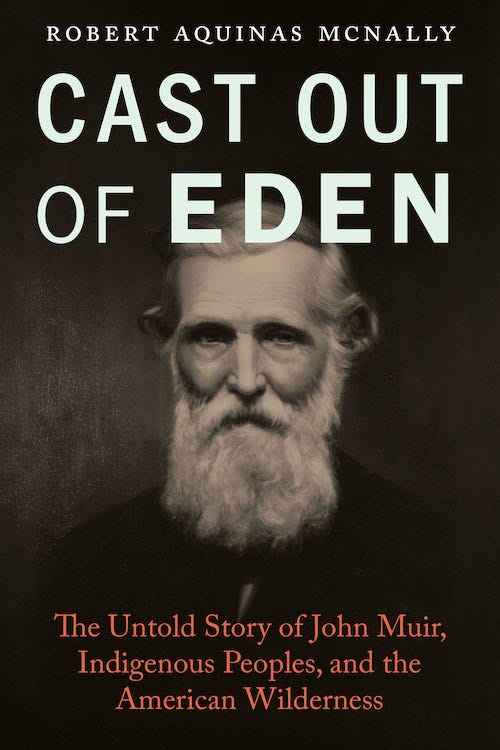

Coming Cast out of Eden events

Sunday, Sept. 29, 12:45 p.m., Berkeley Society of Friends: I'll be talking about the book, John Muir, and the foundations of the national park system in person at the meetinghouse, 2151 Vine St. (near Shattuck), Berkeley, CA 94709. Free and open to all.

Saturday, Oct. 5, 2 p.m., Orinda Books: I'll be reading from Cast out of Eden, answering questions and comments, and signing copies at this in-person event at Orinda Books, 276 Village Square, Orinda, CA 94563. Free and open to all.