The Screaming Children Grownups Need to Hear

With so many self-published books flooding the market, too many good titles languish unnoticed. Here’s an example.

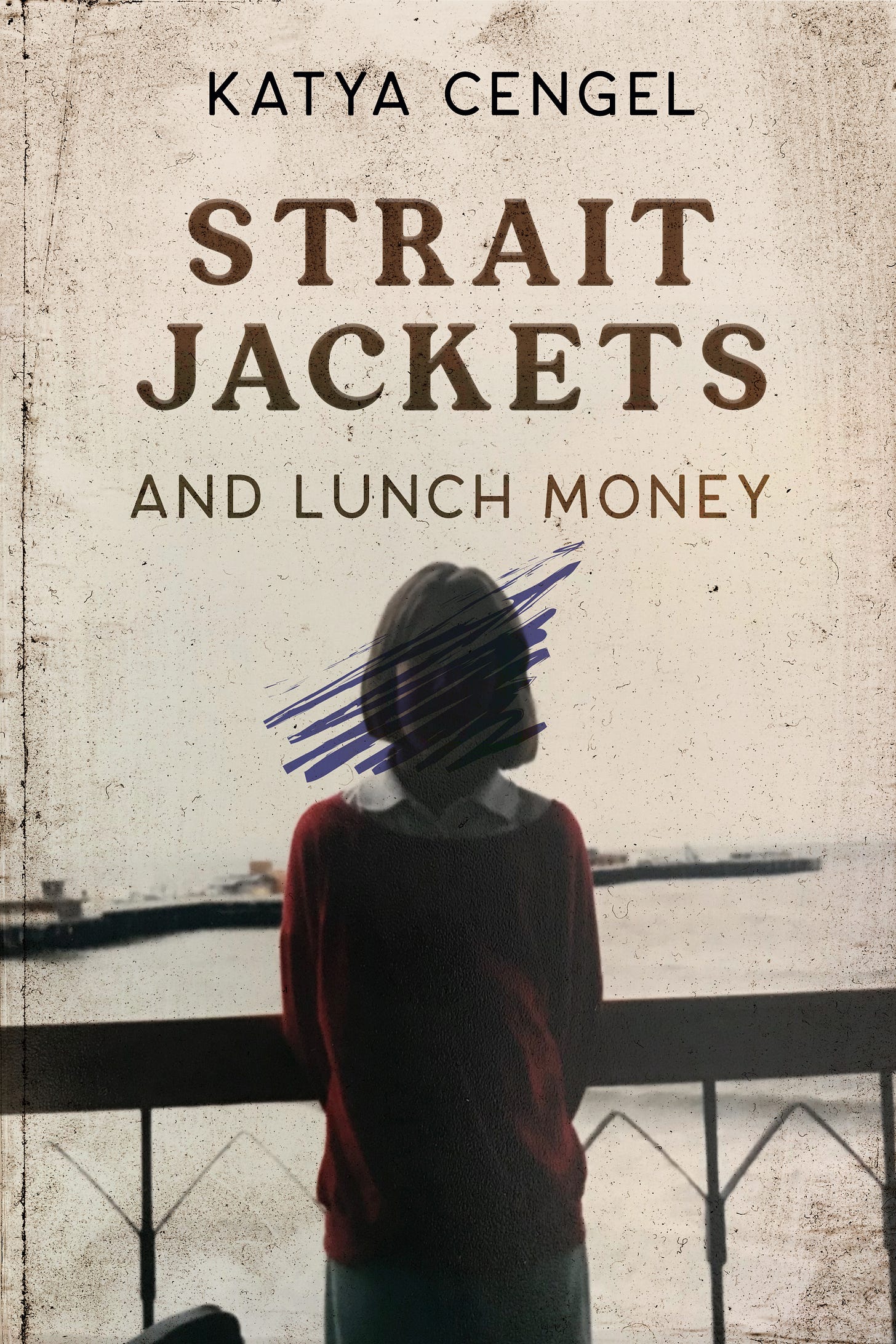

These days more than 4 million new books appear each year, with well over half of them the good, bad, and ugly reads that make up the self-published sector. Given all that noise, excellent books, especially those from independent presses, are too often ignored and overlooked. One such is Katya Cengel’s Straitjackets and Lunch Money, which came out to little fanfare and fewer reviews last year. Cengel is a professional friend, in part because she and I are engaged in a similar quest: telling overlooked stories that need to be heard. Read on and you’ll see what I mean.

What the madeleine dunked in tea was to Proust and his memory of long-lost times, a juvenile detainee strapped into a straitjacket became for journalist and author Katya Cengel. Startled, yet remembering scenes from her own young life, Cengel flipped open her reporter’s notebook and took the writerly leap that grew into this book.

She knew exactly what that straitjacket felt like. As a starving 10-year-old she too had been strapped in, a tactic used to put the force in force-feeding her tiny, wasting body.

Cengel bore other indignities as well, like the nasogastric tube threaded through a nostril and into the stomach to drip Ensure into a body fighting even the idea of food. She did have some small choice in the matter: chocolate, vanilla, or strawberry, as if the flavor bypassing her taste buds made the least difference. It didn’t, of course. All that counted was calories going in. The adults in the room were going to make sure she didn’t die, at least not on their watch.

And she didn’t. “I have never been cured,” Cengel writes. “I’ve found a way to live with the pain — and that’s always included trying to help others.”

Straitjackets and Lunch Money exemplifies her commitment. It is first and foremost a searing memoir of Cengel’s four months in late 1986 and early 1987 as a patient in the Roth Psychosomatic Unit at Children’s Hospital at Stanford University. And it is also a skilled journalist’s deep dive into the broader who, what, when, where, why of unheard children in hospitals, foster homes, detention facilities, and homes without hope. Cengel writes:

This is a story for all the children whose cries we cannot hear because it hurts too much to listen.

Throughout Straitjackets and Lunch Money, Cengel alternates between the memoir of her time at Roth and her contemporary investigation of people she encountered there. She pulls the reader deep into the pain of her child self, then, just when your lungs are bursting and a scream is building, she lifts you to the surface to provide the context and updates revealed by her follow-up reporting.

Cengel’s anguish began after her parents divorced with more than the usual unpleasantry. The court put Cengel and her older sister under a joint-custody arrangement that had them spending one week with Mom and the next with Dad. Mom was competent and concerned, but overwhelmed and stressed. Dad, though, sank into a deep, dangerous, self-centered depression. He lost his job, stopped even pretending to look for work, and parked in front of the TV at all hours, munching stale popcorn and complaining about the lack of money.

His whining gave Cengel an idea: by skipping the noon meal at school she could make a difference. She explains:

Every day my dad gave me a dollar for lunch. If I saved the bills, after a few months, I would have quite a stack. Imagine how happy Dad would be when I gave him that money! I could pay for gas and food.

She was taking care of her parent, which works to the child’s harm, and beginning the slow self-starvation that in time took Cengel down to a mere 55 pounds, put her at risk of sudden death, and sent her to the Roth Unit.

Starving wasn’t just about the money, though. It was also a suppressed scream for help from a child caught in a situation she found impossibly painful. And, as concentration camps and prisons have known for millennia, semi-starvation dulls the capacity to feel and express outrage. In Cengel’s case, her wasting body kept at bay a profound anger at the adult world for abandoning her.

“Most adults were too busy with their own issues to worry about kids,” she writes. “They’d pretend to care, but they didn’t — not really.” Her dad was the worst of all:

He would tell me to eat, and then, when I didn’t, he would eat my food for me. He didn’t really want me to get better; he just pretended he did when other people were watching…. He enjoyed the attention my sickness granted him. He liked the way people felt sorry for him because of his sick daughter. He never made me eat. If he had, I always said I would have stopped starving myself.

The Roth Unit where Cengel was hospitalized ranked as the gold standard of the time and was co-led by an adolescent psychiatrist and an adolescent pediatrician. The patients fell into several groups: diabetics, mostly boys, who refused to eat properly and lurched from one medical crisis to another; self-mutilators, or cutters, mostly girls, who hurt themselves to blot out the worse pain hidden deep inside; one rare and startling case of Munchausen by proxy syndrome, where a parent makes a child sick to bask in the attention he or she receives; and, finally, the girls with anorexia or bulimia or both. Typically eating disorders begin with puberty, and since Cengel was only 10, she was given no single diagnosis.

“I wasn’t anorexic when I entered Stanford, but I was when I left,” Cengel writes. “For a while I was also sort of bulimic.” Her friend Amanda showed her how to throw up on demand to purge the distressing fullness after a force-feeding. She learned other tricks as well, like hiding batteries in her underwear on weigh-in day and concealing medications under her tongue to spit into the trash after. Truth be told, Cengel didn’t want to get better, because then:

People paid less attention to me. I was scared to get too healthy. I was scared that if that happened no one would notice me anymore. I worried that no one would care.

Although care was the Roth Unit’s purported purpose, Cengel found the professionals concerned far more with themselves and their professional lives than with their patients. She sensed that as a child, confirmed it as an adult when she tracked the two medical directors down and interviewed them. For the psychiatrist “patients did not exist outside the medical realm. They were subjects, not sources. Statistics and numbers, not names.” The psychiatric residents who offered talk therapy were assigned not on the basis of a given patient’s mental-health needs, but on the residents’ requirement to check off boxes in their training regimens. The only adults who paid the attention Cengel and the other patients needed were the paraprofessional counselors who guided the kids through the day-to-day. In Cengel’s case, friendly Dan and grandmotherly Sherri were the difference makers.

For in the end Cengel did gain weight, not much but just enough to lift her out of the danger zone by the time her mother’s health insurance ran out. And she learned how to manage her own life, to realize that for her Zoloft was forever, and to discover in journalism the salvation she needed:

I realized there were others who needed to be heard, and not all of them had the ability to write their stories. I had a mission then, a reason to keep going. I could tell their stories.

In the end, Straitjackets and Lunch Money is a difficult yet necessary read. Cengel reports and writes well, keeping her approach simple and direct and building the story incident by incident and interview by interview. The difficulty arises from the pain of the world this book captures, the vast, young suffering it gives voice to. It’s something all of us supposed grownups need to listen to.

More on Straitjackets and Lunch Money

For more about Katya Cengel’s work as a journalist and author, check out her website.

You can listen to Katya talk about the book with host Jeff Schechtman on this California Sun Podcast episode.

Despite the lack of reviews, Straitjackets and Lunch Money scored a bronze medal in memoir in the 2024 Independent Press Publisher Awards.

Copies of Straitjackets and Lunch Money can be had via the usual online outlets, including Bookshop.org, which benefits local bookstores.

If you’d like autographed copies, DimeLibrary.com has them for online order.

Cast out of Eden Online, Friday, June 7

Under the auspices of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, I’ll be offering a talk with Q&A session on the book on Friday, June 7, 10 a.m.–noon PDT. This session will be online only, both live-streamed and recorded for later viewing, so wherever you are, you can take part. To watch my informational video and to register, head over to the OLLI website. Please join me!

Thanks, Bob!

Katya’s story is heart wrenching and it is heartwarming to see her smile today evidencing her healing. There are these children’s stories everywhere, even in my life. At age four, due to my mother’s illness and no child care available, I was brought to an orphanage in Chicago. The nuns told my parents it would be better not to tell me what was about to occur. Pretend a normal outing and then just bring me. I can remember what my parents were wearing that day, the room and hallway, the tall windows to the left-the light pouring through, the smells of the building and the dust mites floating in the light, and especially the habited nun holding me back, small me screaming and squirming to get away, pleading to my parents backs as they walked the long hallway-away- and then they were just gone. The nun kept insisting, all the while, that a banana she was offering would make me feel better. I refused. Weeks later my parents returned, but too late to avoid the abandonment issues so early instilled. I’m seventy six years old, and to this day I have not eaten a banana. I cannot see a banana and not flash back to that day! Safeway to me is a nightmare. My best wishes and congratulations to Katya on her book.