The Story Behind a One-of-a-Kind Picture of John Muir

C. Hart Merriam took the only known photo of Muir in the company of Native Californians. How’d that happen?

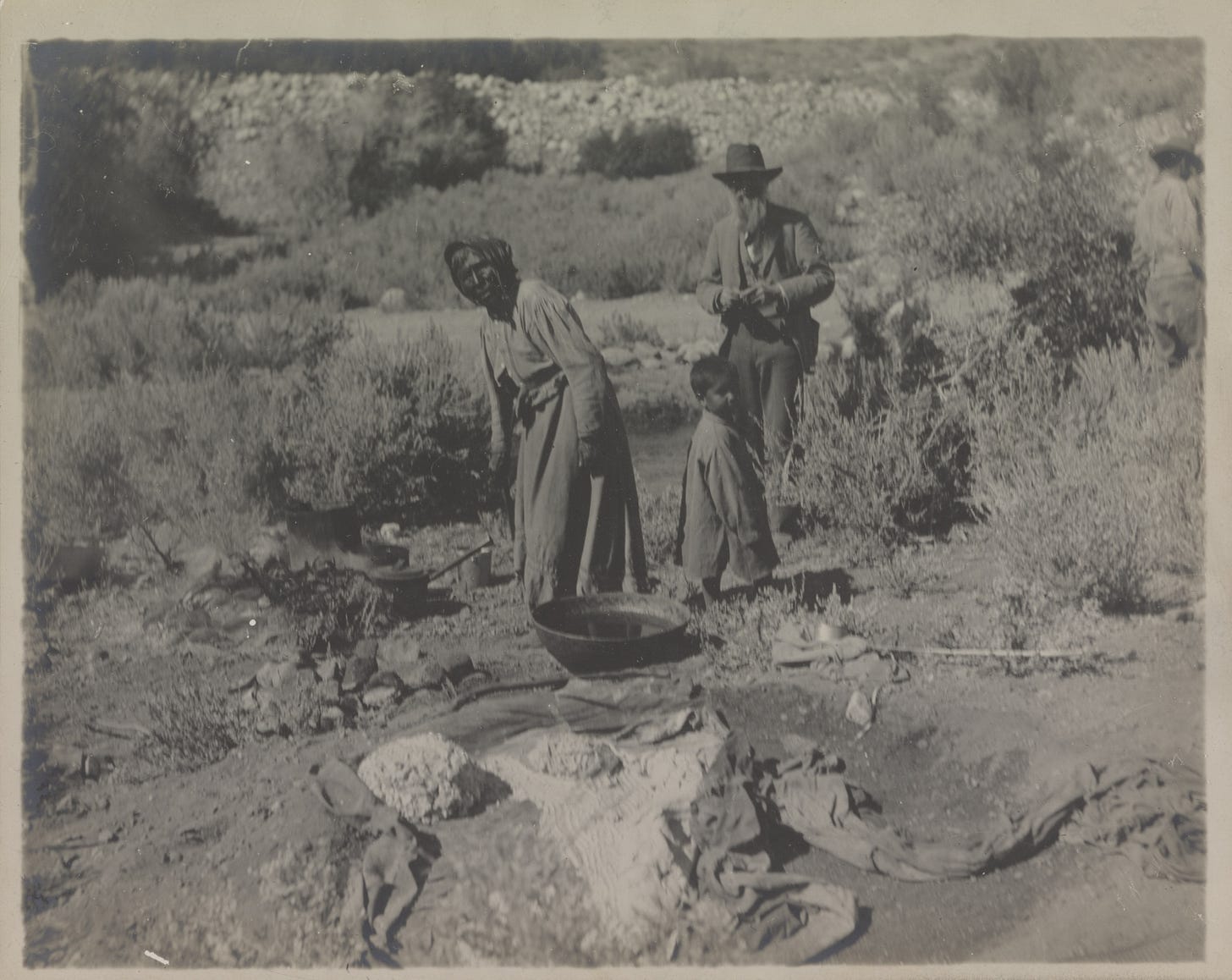

The picture is hardly striking, more quickie snapshot than artistic image. A broad-brimmed hat shading his bearded face against the midday sun and hiding his expression, Muir looks toward the photographer. Between him and the camera stand a woman and a small child, both dark-skinned and shabbily dressed, close to a campfire. The woman wears the look of someone interrupted in the middle of doing something altogether more important than smiling for the camera. The child’s face is quizzical, curious.

Merriam’s caption explains the setting:

Mono Piute [sic] Indians cooking acorn mush on the sagebrush mesa a little north of the west end of Mono Lake. Acorn filter in foreground; John Muir in background. Aug. 31, 1900.

Increasingly fascinated by Indigenous lifeways, Merriam was elated to have stumbled across this family of Kutzadika’as, a.k.a. Mono Lake Paiutes, making lunch from acorns they had carried over the Sierra Nevada from oak groves on the mountains’ western slopes. Taking careful notes as the family’s two women worked, Merriam filled three journal pages with details of the intricate process for leaching bitter tannins from the shelled and stone-ground acorns, mixing the flour with water in a basket, then dropping in superheated stones to cook the mix for about 20 minutes. It “boiled like hot porridge, throwing up multitudes of little volcanoes and sputtering as if on a hot stove,” he wrote. When the mush achieved the desired consistency, the Kutzadika’as fished out the stones, served up the mush, and settled in for lunch. The whole process, Merriam noted, “is essentially the same as among the Mewuk [Miwok], Hoopa, and other Indians.”

Merriam came to the Kutzadika’as’ lunchtime as a scientist long practiced at field observation. When he was only 16, his taxidermy skills won him a position with the 1872 Hayden expedition to Yellowstone, where he collected more than 300 bird skins and 67 nests complete with eggs. At Yale he studied natural history, then went on to Columbia for medical school. While practicing medicine in the Adirondacks, he continued to add to his collection of more than 7,000 mammal specimens and published the scientific description of a new species of marsh shrew, the first of many such papers. Soon recognized as a leader in American mammalogy, Merriam left medicine to join the U. S. Department of Agriculture and build the bureau that grew into the National Wildlife Research Center and the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

On this summer 1900 trip with Muir back and forth over the Sierra Nevada crest between Lake Tahoe and Yosemite Valley, Merriam turned his prodigious observational skills on local tribes as well as birds and mammals. He reported in his journals how Native Californians who had survived the state’s genocide were living lives of unimaginable poverty in places few tourists ever saw. And Merriam was collecting all the while. Fascinated by tribal weaving, he bought dozens of baskets, not the polished objets d’art displayed in museums or sold to tourists but the battered and well-worn utensils that testified to the labors of daily living.

Muir, too, kept journals of his travels. While he had a lot to say about the ample meals he and Merriam were enjoying at local ranches, he wrote not a word about the Kutzadika’as and their lunch of acorn mush. Where Merriam recorded visits to one small tribal village after another, Muir made passing mention of only two. The residents of an encampment in Yosemite Valley left him particularly unimpressed: “Some very old, 100? Crawling in wrinkles and rags, gray, gazing, moving with almost imperceptible motion like bears.” They made baskets for the tourist trade and, he marveled, “still eat acorn mush.”

All of which raises a key question about Muir: Why did he but rarely even notice Indigenous people? Merriam offered answer: Muir ignored whole classes of living beings in the wild:

While he loved the mountains and everything in them, his chief interests centered about the dynamic forces that shaped their features and the vegetation that clothed their slopes. For while he liked to see birds and mammals in the wilderness and about his camps, he rarely troubled himself to learn their proper names and relationships.

It was much the same for Muir when it came to tribal people: they just cluttered up the high-altitude viewshed.

Up next: “No right place in the landscape.”

Jan. 30 book event rescheduled

My talk about John Muir and Cast out of Eden to Rotary of Pleasant Hill, originally set for today, is moving to Thursday, April 3. Sorry for any inconvenience.