To See Such Trees

California’s redwoods drew mystic Thomas Merton toward the spiritual center he had long been seeking.

In 1968 it all seemed to hit the fan. The United States remained murderously mired in the Vietnam War and had been humbled by the fearsome Tet offensive. A sniper shot Martin Luther King, Jr., dead in Memphis, and Bobby Kennedy was killed in Los Angeles. Widespread rioting against war and for civil rights erupted in city after city across the nation, leaving the feeling that the country was coming unstuck. Yet, unnoticed at the time, Thomas Merton arrived in Eureka, California, to search for a new hermitage, an oasis of calm, quiet, and contemplation in a world growing ever more tumultuous.

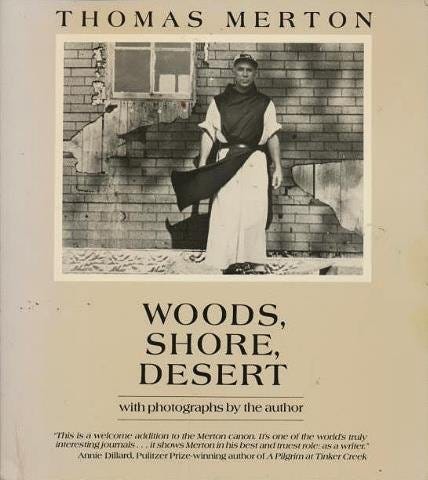

A convert to Catholicism, Merton had joined the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists, at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky 27 years earlier. He captivated the American reading public with his 1948 memoir of conversion and vocation entitled The Seven Storey Mountain, which addressed spiritual longing and became a surprise bestseller. A gifted and philosophical writer who was fluent in both French and English, Merton had a penchant for taking the big questions of existence posed by thinkers from Bernard of Clairvaux to Jean-Paul Sartre in new and unexpected directions.

In his early monastic days Merton was a predictably orthodox Catholic, but as he read widely and wrote his ever-evolving memoirs and essays, he found himself seeking out Buddhist and Sufi masters and wanting for himself less Gethsemani’s silent, communal life of prayer, work, and Catholic liturgy than the contemplative solitude of Asia’s wandering holy men. For a time he lived outside the monastery’s walls in a cinder-block hermitage on a forested knob known as Mount Olivet. Still, his reputation drew a constant stream of visitors seeking spiritual counsel, and solitude was rare. After Gethsemani’s abbot, Merton’s superior, gave him permission to seek out a more sheltered place to live and pray, he headed West to seek out a new hermitage. He saw the journey as a pilgrimage, a search for a holy place, a spiritual home that would allow direct, unbroken contemplation of the Divine.

As Merton flew on a small plane from San Francisco to Eureka, he took note of the volcanic peaks of Lassen and Shasta looming over the mountainous landscape “like silent Mexican gods, white and solemn.” Then he spotted the trees whose reputed grandeur had drawn him to the North Coast:

The redwood lands appear. Even from the air you can see that the trees are huge. And from the air too, you can see where the hillsides have been slashed into, ravaged, sacked, stripped, eroded with no hope of regrowth of these marvelous trees.

Once landed, Merton headed south on Highway 101. The wrenching desolation of the clearcuts gave way to wild grandeur as he entered the old-growth groves of Humboldt Redwoods State Park:

Driving down through the redwoods was indescribably beautiful along Eel River. There is one long stretch where the big trees have been protected and saved — like a completely primeval forest. Everything from the big ferns at the base of the trees, the dense undergrowth, the long enormous shafts towering endlessly in shadow penetrated here and there by light. A most moving place — like a cathedral.

Merton lived among the trees at Redwoods Monastery, a community of Trappist nuns 20 miles outside Garberville, where he offered conferences on spirituality for the sisters and wandered the wild coast of what would become Sinkyone Wilderness State Park. From there he headed through San Francisco, where he had dinner with poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, to northern New Mexico. There he lived with a Benedictine monastic community, missed meeting painter Georgia O’Keefe, and drank in the desert’s dry silence.

When Merton returned to Gethsemani and revised his journal to become the book Woods, Shore, Desert, he realized how, of all he had encountered on his pilgrimage, the redwoods drew his soul the most deeply. Throughout his spiritual quest, he sought what he called le point vierge, the “virginal point” or “blank place” in the soul that is the spring of all love and the very purpose of contemplation. The redwoods were the perfect natural embodiment of that special place within: ancient, untouched, wordless. “The silence of the forest is my bride,” he had written from his hermitage on Mount Olivet. Now, after he walked within towering, old-growth redwoods, Kentucky’s oaks and piney woods felt all together too small and paltry. He vowed to return to the big trees:

The worshipful cold light on the sandbanks of the Eel River, the immense silent redwoods. Who can see such trees and bear to be away from them? I must go back.

Sadly, Merton’s pull to return to “such trees” went unfulfilled. His sudden end at the age of only 53 came neither in Kentucky nor on California’s North Coast, but at an interfaith monastic conference outside Bangkok, Thailand, in December 1968, only months after his redwoods revelation. Coming out of the shower, Merton suffered a sudden cardiac arrest, reached out as he fell to the floor, and grabbed a fan whose faulty wiring electrocuted him. His body was flown home on a U.S. military aircraft transporting war dead back from Vietnam and buried at Gethsemani, far from the majestic trees his heart yearned for. Yet perhaps, in the arc of his fall, even as spirit left body to enter the cosmos, he saw himself once again among the redwood groves along the Eel River.

Thirty-five years later, David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk who lived and wrote, as Merton did, on the border of Christianity and Eastern religion, recalled:

A vivid image in my memory: Thomas Merton standing in a redwoods clearing. “Here is where it all connects,” he says softly.

Indeed, it is.

Such peace in these trees. Thank you for bringing this to us/me today. Lovely!

Stunning piece! The concept of le point vierge as embodied in the redwoods is something I never connected before, but it makes total sense when thinking about how those ancient groves create a kind of cathedral silence. I hiked through Huboldt Redwoods last summer and dunno if it was the scale or the stillness, but that same wordless pull definitely lingered weeks after leaving.