What Makes a Genocide Genocide?

International law raises such a high bar that even some of the worst atrocities fall short. Still, California in the 19th century makes the cut.

When California set about the genocide that Gov. Gavin Newsom acknowledged five years ago, the legal term to describe it didn’t yet exist. That wouldn’t happen for almost another century, thanks to a Polish lawyer who never could stomach the idea of states getting away with wholesale slaughter.

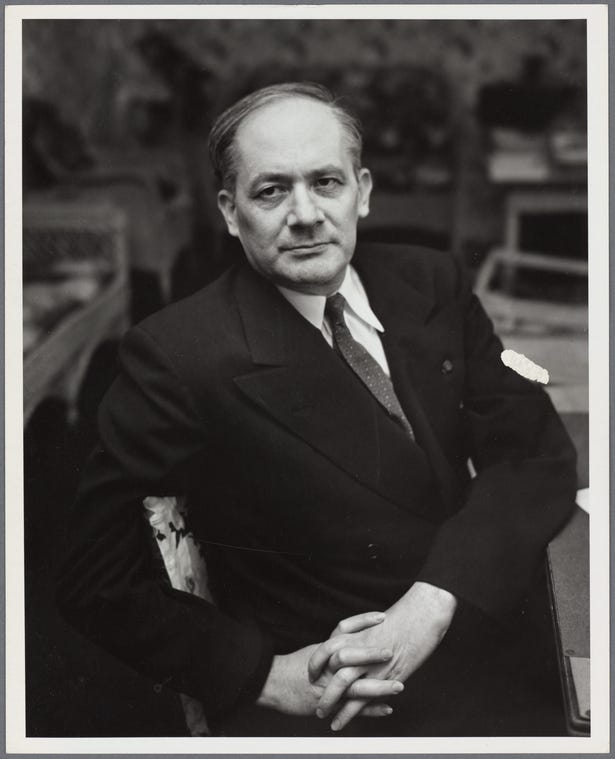

His name was Raphael Lemkin. While studying law between the two world wars at Poland’s University of Lvov — now Lviv and in Ukraine — he focused on the legal vulnerability of minority communities to lethal state violence. The most recent example was the killing of up to a million Armenians by the Ottoman Empire in the closing years of World War I. When Lemkin asked one of his professors why the Ottomans couldn’t be prosecuted for mass murder, the professor told him that the doctrine of national sovereignty gave leaders the right to do as they saw fit in internal affairs.

Lemkin disagreed:

Sovereignty, I argued, cannot be conceived as the right to kill millions of innocent people.

Lemkin’s scholarly concern became personal some years later when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939 and besieged Warsaw, where he was living. Knowing that as a Jewish intellectual he was a prime Nazi target, Lemkin escaped Poland to Sweden and later emigrated to the United States. There he watched the Nazi horror unfold across Europe. Lemkin recognized in the Third Reich’s killing campaigns a re-enactment on an even larger scale of what the Ottomans had done to the Armenians.

First, he had to give it a name. Lemkin’s 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe introduced the word “genocide” by combining the Latin roots genus (race, tribe) and occidio (massacre, extermination). Lemkin’s goal was to create a legal structure that would define what he called “the crime of crimes” and allow prosecution.

Lemkin made it clear that what the Nazis were doing stood out for its scale, the sheer numbers killed, not for its historical uniqueness. Genocide itself was, Lemkin wrote, “an old practice in modern development.” In other words, some people have been doing this to other people for as long as forever.

He cited as an example Rome’s destruction of the North African city-state of Carthage in 146 BCE, which resulted in the killing of most of the city’s residents and the sale of the survivors into slavery. Another instance was the Sack of Magdeburg in 1631, during the Thirty Years War, when a Catholic army butchered about 80% of the city’s Protestant residents. When Lemkin died suddenly, he was working on a book about historical genocides that included the destruction of North America’s Indigenous peoples.

Lemkin’s tireless advocacy and lobbying led to a resolution on genocide that passed the U.N.’s General Assembly in 1948 and became international law upon ratification in 1951. The resolution was incorporated into the Rome Statute of 1998 creating the International Criminal Court, the legal body that holds jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes of aggression, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Lemkin himself had an expansive notion of genocide that included the willful destruction of a people’s language and culture. However, as a result of the endless horse trading that goes on in legislative bodies like the U. N. General Assembly, the 1948 resolution came out both narrower than Lemkin’s concept and harder to prove:

Genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Killing members of the group

Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Imagine yourself a prosecutor before the ICC in The Hague trying to win a genocide conviction against the leader of a most murderous country. Just showing that said leader did horrific things like kidnapping children — we’re looking at you, Vladimir Putin — isn’t enough. You also need to demonstrate the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part,” a specific group. That’s the tricky part, the high bar to be hurdled to secure conviction.

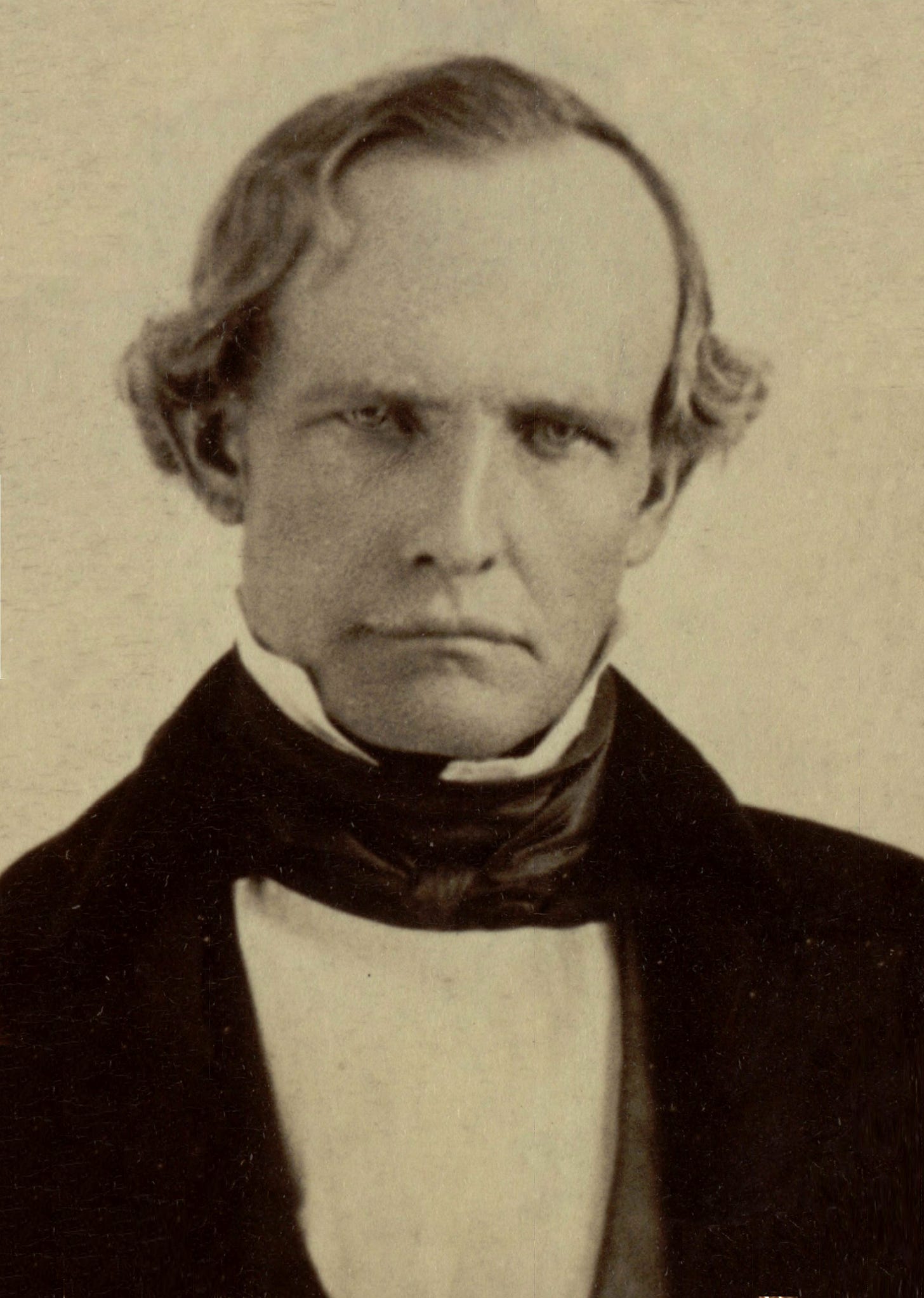

Most leaders bent on genocide these days play their cards close to the vest and avoid public statement of their intentions. Not so back in 19th-century California, when genocide was called extermination. Peter Burnett, the new state’s first civilian governor, spelled it out in his state-of-the-state speech to the legislature on Jan. 7, 1851.

Most of Burnett’s long, windy talk focused on the “Indian problem” as an impediment to California’s progress toward unbounded prosperity. There was but one way out of the dilemma:

The two races must ever remain at enmity. That a war of extermination will continue … to be waged until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected…. The inevitable destiny of the [Indigenous] race is beyond the wisdom or power of [the white] man to avert.

There it was, a statement of genocidal intent as stark and incontrovertible as anything from the 1942 Wannsee Conference, where the Nazi elders signed on to the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” A prosecutor assigned the California case would label Burnett’s speech Exhibit A as slam-dunk evidence of genocidal intent.

Of course, what a governor says and what a state does can differ markedly. In 1851 California, however, the legislature soon proved more than willing to put the state’s money where Burnett’s mouth was.

Tonight, July 11, 7 p.m., in Berkeley

I’ll be reading from Cast out of Eden, taking questions and comments, and signing copies at Books Inc., the West’s oldest independent bookstore, located at 1491 Shattuck Ave., near the corner of Vine St., in north Berkeley, Calif. Please join me!

Cast out of Eden heads to the Commonwealth Club

On Wednesday, July 24, 5:30–6:30 p.m., I’ll be talking about the book in conversation with Andrew Dudley, cohost and producer of the independent media network Earth Live, and signing copies at the club’s Nature Forum in-person meeting, 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco, Calif. Details and ticketing here.

Bob,

Your work is long overdue and much needed.

COOE should be required reading.