California’s Native Slaves

Admitted to the pre–Civil War United States as a nominally free state, California devised a workaround to keep the locals in bondage anyway.

John Muir’s successful orchard operation, the one that earned him and his heirs an estate worth millions, followed a pattern found in California from the Spanish invasion of 1769 onward. As long as there has been European-style agriculture, there have been workers forced to toil long and hard, often fatally, in fields, orchards, and vineyards. Like many things Californian, it began with the missions.

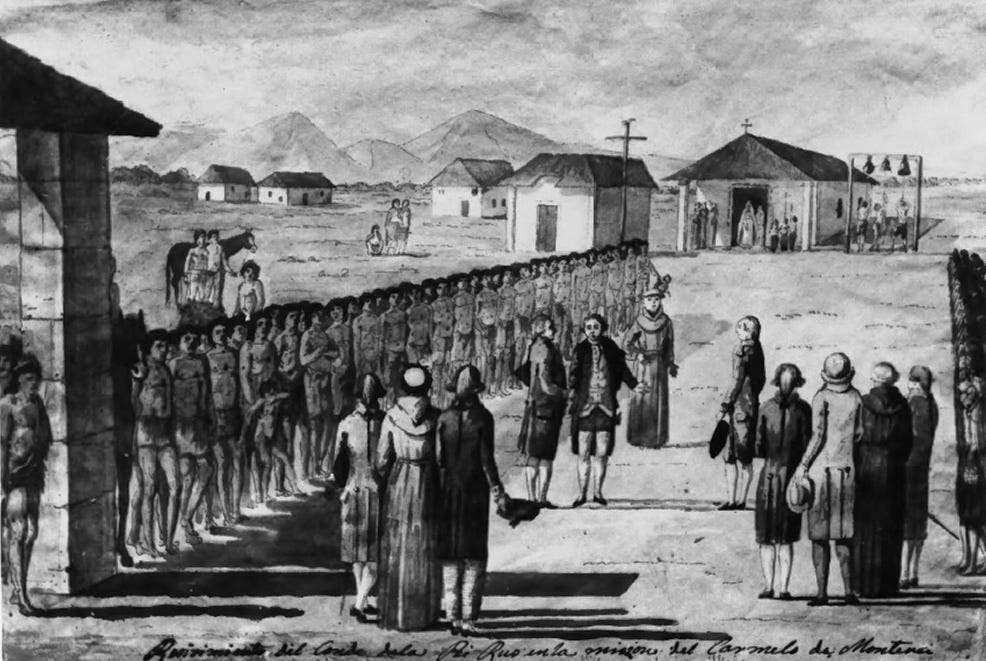

The friars saw their role as saving pagan souls and instilling civilization by teaching Native Californians Catholicism and field work. Baptism indebted tribal neophytes to the missions, which provided inadequate housing and minimal food and owned their labor on farm and ranch. Never mind that neophytes died in the missions at up to six times the mortality rate of slaves in the American South, largely from poor nutrition worsened by diseases ranging from smallpox to syphilis. The friars expressed little dismay over the losses. As they saw it, the baptized went to heaven, which was the missions’ whole point. Plus, there were always more Indigenous people back in the hills, woods, and mountains to replace the dead. Recruitment consisted of sending soldiers to round them up and bring them in — for the good of their souls, of course.

After Mexico secularized the missions in 1833, Spanish-speaking Californios as well as American and European immigrants picked up where the church left off, continuing the system of debt peonage to bind Native Californians to particular landholdings and effectively enslave them. The most notorious was Johann — later John — Sutter.

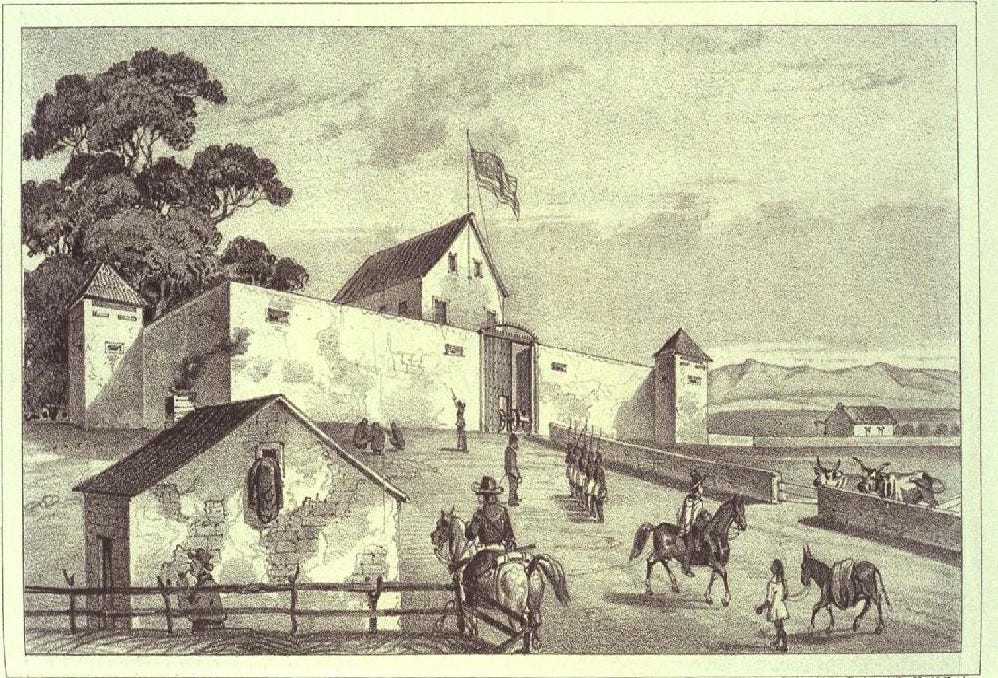

A Swiss immigrant, Sutter settled in what is now Sacramento and built a fortified town he called New Helvetia, borrowing the Roman name for Switzerland. Sutter forced the local Nisenan and Miwok peoples to work for him, locked them up overnight in dormitories without latrines, fed them at troughs that ran a slurry of par-cooked animal offal and grain, and kept them slaving long days among his crops and livestock. Whenever any of his conscripted workers ran off, Sutter’s private militia — dressed like Gilbert and Sullivan extras in surplus uniforms picked up cheap from the Fort Ross Russians on the coast — hunted them down, tortured and killed a few for sadistic example, then dragged the survivors in chains back to New Helvetia.

The American military governors who ran California from 1846 until the territory established civilian rule in the closing months of 1849 were careful not to upset the system that supported the local economy. With statehood, however, the newly installed legislature and first civilian governor Peter Burnett were facing a new challenge: a severe labor shortage brought on by the gold rush. Everybody and his brother had left their jobs and lit out for the diggings; workers were not to be had.

The first law passed by the new legislature and signed by Burnett aimed to ensure a steady, cheap supply of Indigenous labor to fill the gap. It was named, with malicious irony, the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.

Fashioned after the Black Codes of the pre–Civil War South, the new law effectively compelled Native Californians to work for whites. Convict leasing was one such compulsion. A landowner could visit the local jail, pay the fines of tribal people arrested for nothing more criminal than “loitering,” and require them to work off the debt.

Growers, most notably vineyards and wineries around Los Angeles, turned the law into a system of repeat involuntary servitude. Farmhands were paid off on Saturday night in aguardiente, a potent brandy. The resulting nocturnal merry-making invited raids by the sheriff and his deputies, who arrested Native Californians by the dozens, often for no good reason, and locked them up. Growers came by the county jail on Sunday, paid the fines, and assembled their convict work crews for the upcoming week. Come next Saturday, the cycle repeated.

Horace Bell, an early American Angeleno who later became a lawyer and newspaperman defending the poor, knew what he was seeing:

Los Angeles had its slave mart, as well as Constantinople and New Orleans — only the slave at Los Angeles was sold fifty-two times a year as long as he lived, which generally did not exceed one, two, or three years under the new dispensation…. These thousands of honest, useful people were absolutely destroyed in this way

The Thirteenth Amendment and post–Civil War federal laws undermined the legal foundation of California’s system of short-term enslavement. It might have persisted, though, except for the fatal fact Bell pointed out: Native Californians were being killed off by state-sponsored genocide, which included the slave labor sanctioned by California law as well as disease, murder, and massacre.

By 1870 the Native population, which numbered 150,000 in 1846, had dwindled to just 30,000. And it would continue to crumble, to a mere 15,000 by 1890. Given these deadly demographics, Native Californians were vanishing as a source of abundant, low-cost farm labor. Yet California’s new industrial agriculture needed a hands-on work force as captive and cheap as tribal people had been. That’s where the Chinese came in.

Up next: From China’s Pearl River Delta to John Muir’s farm.

Muir birthday and Earth Day celebration this Saturday

The John Muir National Historic Site in Martinez, Calif. — only a few miles from where I am writing these words — will mark Earth Day (April 22) and Muir’s 187th birthday (April 21) from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Saturday, April 26. This event features music, food vendors, exhibits, tours of Muir’s mansion home and orchards, and long-bearded Muir re-enactors. Easy parking and shuttle service nearby, and it’s all free. Details here.

Robert- This is an interesting deeper look at slave-trade specifically in California. I never knew about certain particulars related to Muir and now feel like I have a greater understanding of what happened there. Thanks for sharing!