For all the wealth his Martinez farm brought him, Muir never enjoyed the enterprise or the place. The long, hard workdays felt much too much like what he had known on the Wisconsin homestead under his tyrannical and abusive father. Farming then and now was a misery to be endured only because it made money.

“I am lost and choked in agricultural needs,” he wrote to Millicent Shinn, editor of The Overland Monthly, explaining why he had no new articles to send her:

Work is coming on me from near and far and at present I cannot see how I am to escape its degrading vicious effects. Get someone to write an article on the vice of over-industry, it is greatly needed in these times of horticultural storms.

He made much the same lament to S. Hall Young, a missionary and backcountry buddy he knew from his Alaska travels:

I am losing the precious days. I am degenerating into a machine for making money. I am learning nothing in this trivial world of men.

After a full decade driving the industrialization of California agriculture, Muir happily turned day-to-day farm management over to brother David and brother-in-law John Reid, who had moved out from Wisconsin. In time he sold part of the farm and leased out the rest.

From the time John Muir married Louie Strentzel in 1880 until the end of his life in 1914, the Strentzel farm near Martinez remained his home base, the center of his family, a legacy to daughters and grandchildren, an economic boon to siblings and in-laws, and the source of his wealth. Yet Muir never invested in Martinez emotionally or spiritually. Even while he was courting Louie, he dissed the Contra Costa countryside:

The ranch and the pasture hills hereabouts are not very interesting at this time of the year. In bloom-time, now approaching, the orchards look gay and Dolly Vardenish, and the home-garden does the best it can with rose bushes and so on, all good in a food and shelter way, but about as far from the forests and gardens of God’s wilderness as bran-dolls are from children.

For all the years he spent there, Muir never felt at home in Martinez; always he was drawn elsewhere, higher up, into the Sierra Nevada. Late in his life, he told a visiting journalist that the farm was “a good place to be housed in during stormy weather, to write in, and to raise children in, but it is not my home. Up there is my home,” gesturing eastward, toward Yosemite.

There was the wild and wilderness, he was saying, and there was the city and civilization. The farm, for all its rural reality, belonged to the latter. Where wilderness was to be preserved at all costs as sanctuary and refuge, the city and its industrialized croplands existed for commerce’s sake, not nature’s. Profitable use was the point.

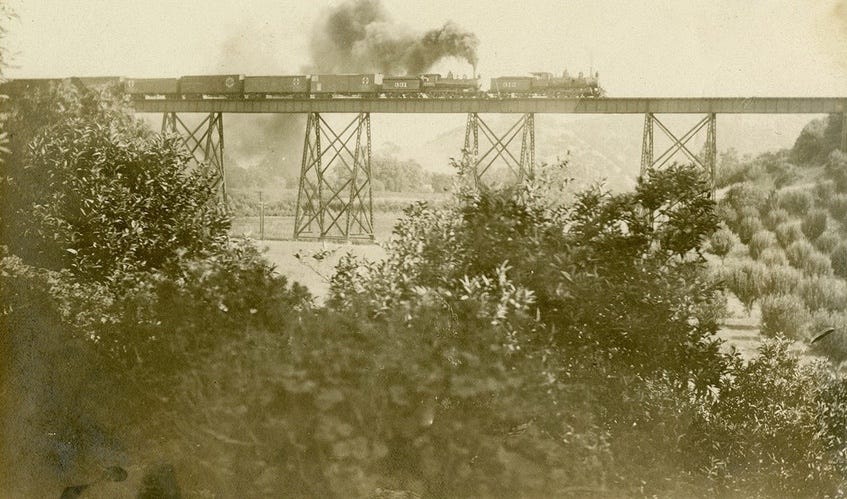

Muir understood who buttered his Martinez bread. Almost simultaneously with the publication of Frank Norris’s The Octopus, the classic novel that portrays the railroad and its greedy barons as the enemy of California’s farmers, Muir did a favor for the railway industry that delivered his crops to market. When the Santa Fe Railroad constructed a trestle across the Alhambra Valley just south of the farm’s boundary, he donated a portion of his land for use as a station. The gesture was Muir’s way of saying thanks.

To this day a trestle crosses the canyon there, an elevated span that symbolizes the bright line Muir drew between wilderness, which demands protection as sacred sanctuary, and cultivated land, which welcomes industrialization and commercial use. He was hardly the first to do this, nor the last. Indeed, this sharp divide between wild and civilized continues to underlie the way 21st-century Americans look at wilderness and their overall responsibility to the planet.

In defining sanctuary by its boundaries, Muir made it clear that only some ground was sacred. As author and critic Rebecca Solnit writes, “To say that Yosemite is Eden is to say that everywhere else is not.” The wild temple became a stand-in for Creation’s garden, and the land outside it comprised the secular realm where humankind was consigned after serpent, forbidden fruit, and Fall.

Muir made it clear that sacred wilderness had to be defended against the invading secular. When God sent Adam and Eve packing, he stationed angelic cherubims with a flaming sword at Eden’s entrance to keep the first couple from slipping back in. Seeing the damage done by grazing sheep in a Sierra meadow, Muir advocated this Biblical strategy for the high country:

One might reasonably look for a wall of fire to fence such gardens, for as far as I have seen, man alone, and the animals he tames, destroy these gardens.

In the campaign to preserve the Sierra Nevada’s sacred sanctuary, Indigenous people had to be cast out, just like Adam and Eve. After all, their all too human bodies and lives were woven into the wilderness, polluting it. They hunted woods and plains and fished streams, harvested wild rye and pine nuts and acorns, built huts and houses, and burned meadows seasonally to favor rabbits and deer and to thin the oak thickets of shade-loving seedlings. As Muir saw it, tribal peoples desecrated nature’s sanctuary. Yosemite’s Eden was a temple for contemplation, not a homeland. The Indigenous had to go.

Up next: Hiding in plain sight.

Recent praise for Cast out of Eden

Calling the book “a provocative and insightful story,” reviewer Doug Sheflin of Colorado State University says it “demonstrates how Muir came to see Indigenous people and wilderness as mutually exclusive and suggests how that separation became so central to the creation of national parks due in part to his influence.” Sheflin’s review is available on H-Net.Online.