The Company He Kept: "The Passing of the Great Race"

John Muir’s ally Madison Grant wrote the popular book articulating the white supremacist ideology that led, among other horrific outcomes, to Nazism.

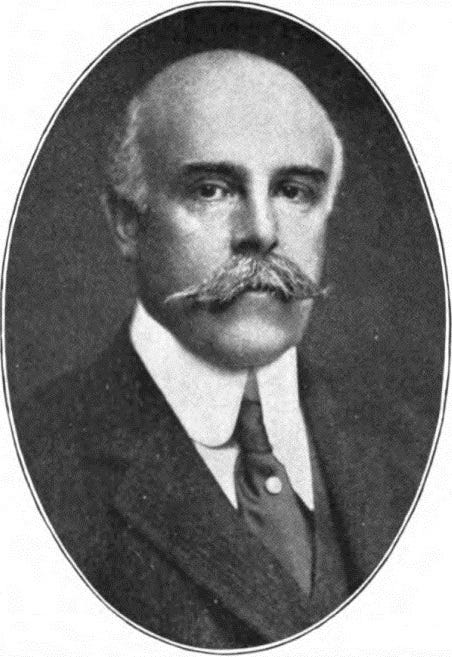

The supporters and influencers whom Henry Fairfield Osborn recruited into Muir’s save-Hetch-Hetchy campaign in the early years of the 20th century shared his arrogantly white-supremacist views. The most prominent and most notorious of this prominently notorious gentlemen’s club was Osborn’s long-time friend and collaborator Madison Grant.

Like Osborn, Grant came from ancestral lines privileged by power and wealth since colonial times. Sent to Germany in adolescence to study with private tutors, Grant returned to the United States to graduate from Yale and earn a law degree at Columbia. He passed the bar and for a time maintained a law office. But, with no need to earn a living beyond his massive inheritance, Grant turned into a professional joiner, founder, and leader of elite WASP clubs, most of them alarmed by the surge in immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe — all those Catholics and Jews! — that was rapidly changing the face of America.

For many upper-crust Americans, particularly those like Osborn and Grant who thought themselves descended in body and spirit from Northern European pioneers, this transformed United States looked dark and menacing. This point of view was well articulated by Francis Amasa Walker, one-time superintendent of the census and president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who wrote in The Atlantic:

The entrance into our political, social, and industrial life of such vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions, is a matter which no intelligent patriot can look upon without the gravest apprehension and alarm. They are beaten men from beaten races, representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence.

Grant shared Walker’s down-the-nose point of view. An avid and accomplished hunter and outdoorsman, Grant also recognized immigration as a threat not only to America’s growing cities but also to its fast-fading game populations and wild spaces. Grant and Osborn shared the conviction that wilderness preservation, immigration restriction, and white supremacy sprang from the same root: pure wild, pure nation, pure race.

While the Hetch Hetchy fight boiled and simmered through the first decade of the 20th century, Grant was working on a book manuscript that elaborated his pseudo-scientific white supremacy. Entitled The Passing of the Great Race: or, The Racial Basis of European History, the draft so impressed Osborn that he served as one of Grant’s beta readers, proposed revisions, wrote a laudatory preface, and put the manuscript in front of Charles Scribner, his publisher as well as an old Princeton friend. The conservative, patrician Scribner liked what he read. He signed a publishing contract with Grant and supervised the project himself before passing it on to famed editor Maxwell Perkins, who would later go on to handle F. Scott Fitzgerald and Earnest Hemingway.

The first edition of what would be four rolled off the press and into bookstores in 1916, where it posted modest but steady sales based on praise-filled reviews. Theodore Roosevelt lauded The Passing of the Great Race as “a capital book; in purpose, in vision, in grasp of the facts our people most need to realize.” The New York Herald lauded it as “a profound study of world history from the ethnological standpoint.” pointed to Grant’s “originality, conviction, and courage.” Scholarly journals, like Science and the Journal of Heredity, groused about the book’s lack of footnotes and partisan tone yet largely agreed with its premises and conclusions.

The principal dissenter was anthropologist Franz Boas, who was already taking steps to distance his academic profession from pseudo-scientific racism. He rejected Grant’s racial hierarchy and saw the book as ideological screed rather than scientific analysis. Most general readers, however, didn’t care what a fusty academic like Boas thought. After all, they asked, wasn’t he Jewish?

Boas had a point, though: practically nothing in The Passing of the Great Race was original. The book amounted to a gathering of other authors on hot topics, from anti-Semitism and Christ’s putatively Nordic heritage to mixed-race breeding as the fast track to cultural decline. Because Grant argued for these borrowed racist ideas in a clear, entertaining style that non-scholars could grasp, the book worked commercially.

With The Passing of the Great Race making its way to libraries, bookshelves, and coffee tables, the biological threat that inferior races like the swelling floods of Eastern and Southern European immigrants posed to old-stock Americans moved from private speculation to public fact.

The time for action had come, Grant declared:

Neither the black, nor the brown, nor the yellow, nor the red will conquer the white in battle. But if the valuable elements in the Nordic race mix with inferior strains or die out through race suicide, then the citadel of civilization will fall for mere lack of defenders.

Nordic Euro-America had its back against the racial wall; the slow slide toward the bottom had already begun:

If the Melting Pot is allowed to boil without control and we continue to follow our national motto and deliberately blind ourselves to “all distinctions of race, creed, or color,” the type of native American of Colonial descent will become as extinct as the Athenian of the age of Pericles, and the Viking of the days of Rollo.

Despite its singular focus on race, Grant’s master work, like H. F. Osborn’s later Man Rises to Parnassus, largely skipped over the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Defeated and dispossessed, felled by violence, disease, and poverty as evolution dictated, they mattered to Grant only as inferior gene pools. History’s inexorable racial forces had already pushed tribal Americans aside. They could hope for nothing beyond physical survival, and even that was no guarantee.

Grant’s impassioned screed against humankind’s lower orders drew readers not only in the United States but also in Europe, where a fierce blood-and-soil nationalism was rising in the aftermath of World War I’s destruction. The German translation of Grant’s book, Der Untergang der Grossen Rasse, won many admirers. Among them was an up-and-coming Bavarian political star who penned an excited fan letter to Grant. “The book,” wrote Adolf Hitler, “is my Bible.”

New national monument addresses forced assimilation

Intended to honor the tens of thousands of tribal American children who were separated from their families, languages, and homelands and confined in boarding schools that trained them for menial jobs, the new national monument occupies the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School some 25 miles west of Harrisburg, Pa.

Carlisle founder Richard Henry Pratt, a retired military officer, established the school to ensure “that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Under a seeming rubric of discipline for the purpose of assimilation, Carlisle students were abused mercilessly to “kill the Indian.” In fact, children died at the school and others like it and were buried on the grounds, often in unmarked graves.

In July, the Department of the Interior released the final volume of a report charting the damage and death wrought by the boarding schools and demanding, among other measures, an apology to Native America. On Oct. 25 Pres. Biden delivered that apology. The new Carlisle Federal Indian Boarding School National Monument represents another step on the road to healing this longstanding wrong.

And now a word from our sponsor

Through Tuesday, Dec. 31, the University of Nebraska Press and its many imprints are offering 50% off on every title. That includes not only my books, The Modoc War and Cast out of Eden, but also some 4,000 additional titles across a wide range of genres in both fiction and nonfiction. Now, that’s a holiday deal for folks who love to read.