Then and Now: More Migrants, More Hate

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, immigrants were pouring into the U. S. Much the same is happening today, and the reaction then raises alarm now.

In the closing days of 1890, the Seventh Cavalry — the unit once commanded by George Armstrong Custer — surrounded some 350 Minneconjou (Mnikowoju) and Hunkpapa (Húŋkpapȟa) Lakotas at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, and killed most of them for no good reason — except, perhaps, to avenge the self-inflicted disaster of Little Bighorn 14 years earlier. Wounded Knee was the last massacre masquerading as a battle in the western Indian wars, and the tragedy marked their end.

In 1890 as well, the Census Bureau declared the American frontier over and done with. No longer, according to census statistics, was there an ongoing westward migration of Euro-Americans into once-Indigenous homelands emptied by force or treaty of their tribal inhabitants. Frederick Jackson Turner turned this signal event of demography and conquest into his classic essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” He concluded that “now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

All the while, American cities fueled by rapid industrialization were growing by long leaps and great bounds. New York City, as one example, exploded from just under 814,000 residents in 1860 to over 3.4 million by 1900, due largely to a rising tide of immigrants from southern Italy, Hungary, the Austrian Empire, and Czarist Russia. The trend alarmed old-stock, WASP Americans disconcerted by people who didn’t look like them. To Francis Amasa Walker, president of MIT and as WASP as they come, the newcomers represented “beaten men from beaten races, representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence.” Their arrival presaged a darkening future for the country.

Walker’s sentiment ran up hard against the welcoming Emma Lazarus lines inscribed on the Statute of Liberty:

… Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Walker and his many allies wanted to slam the golden door shut and keep immigrants out. In the end they got their way.

Currently the U. S. is experiencing a surge of immigration exceeding the rising tide that alarmed Walker et al., according to a recent analysis by The New York Times. In 1890 the proportion of foreign-born people living in the U.S. was 14.8%; in 2023 it hit 15.2%.

The similarities between immigration back then and right now are more than statistical. President-elect Trump has long espoused anti-immigrant rhetoric echoing Walker’s denunciation of “beaten men from beaten races.” Trump cites immigrants as the source of crime in America, because, he claims, the surge through the southern border “is poisoning the blood of our nation. They’re coming from prisons, from mental institutions — from all over the world.” And Trump cares not a fig that this language echoes the blood-and-soil nationalism Adolf Hitler espoused in Mein Kampf. It serves his xenophobic purpose of pitting “us” against “them” for political advantage.

Anti-immigrant sentiment in the early 20th century led to a series of federal laws intended first to slow, then to stem the flow from that era’s “shit hole” countries. The effort culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned all Asians, restricted newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe to but a tiny trickle, and set limiting quotas even for immigrants from Northern Europe. The Immigration Act governed immigration into the U.S. for the next 41 years.

In the process it contributed indirectly to the Holocaust, a connection illustrated by the voyage of the St. Louis. Carrying 937 European Jews seeking to escape the Nazis in 1939, the ship was denied entry to the U. S. because accepting its passengers would exceed the annual immigration quota for Germany and Austria. Turned away as well by Cuba and Canada, the St. Louis had no option but to return to Europe. Some of the passengers did find refuge outside the Reich, but by war’s end 254 had died in occupied Europe’s ghettoes and death camps.

That bitter end would not have bothered Madison Grant, one of the behind-the-scenes organizers and lobbyists who built the ideological and political movement leading to the Immigration Act of 1924. A New York patrician, he recoiled at the very sight of Jewish immigrants in his native city’s streets. Grant’s popular The Passing of the Great Race argued that only the Northern Europeans he called Nordics were biologically fit to rule the world’s lesser races and that immigrant newcomers were swamping the elite Nordic gene pool to the country’s detriment. Adolf Hitler named Passing his bible, and his endorsement made the book essential reading on heredity and race for all good Nazis.

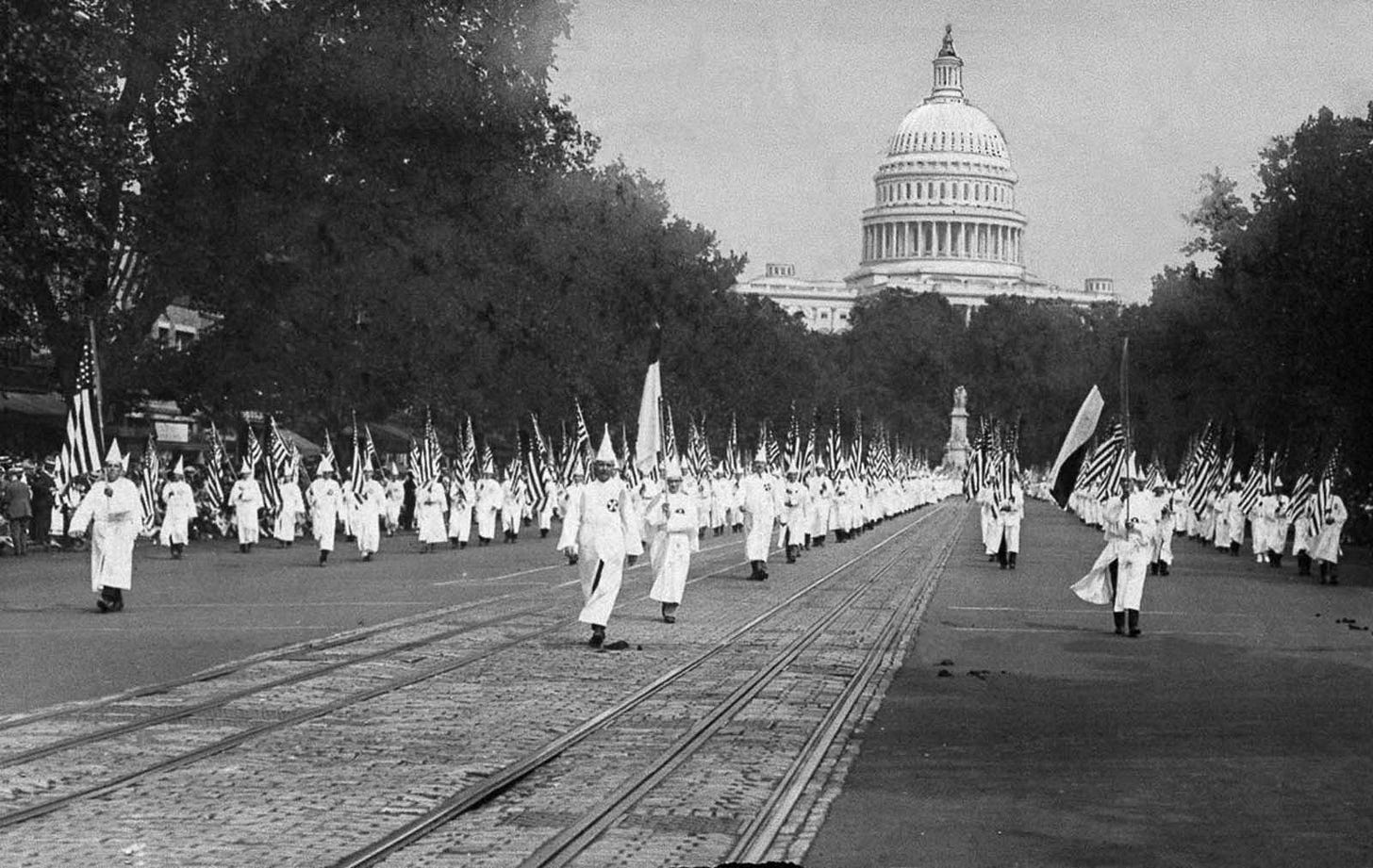

Even as The Passing of the Great Race spread Grant’s racist ideology, the Ku Klux Klan was expanding faster than ever before, reaching a membership of millions that extended well beyond the Deep South. Appealing to militant white Protestants, the KKK held rallies and burned crosses to oppose Jews, Catholics, Eastern and Southern European immigrants, and Blacks. The KKK became so mainstream that in 1926 an estimated 30,000 Klansmen and Klanswomen marched down Pennsylvania Ave. in Washington, D.C., in robes and hoods, their faces uncovered. They were proud to let their friends and neighbors know who they were.

The following year, a Klan rally in the Jamaica, Queens, section of New York City turned rowdy, and seven men were arrested. One of them, soon released without charge, was a 21-year-old named Fred Trump.

Trump’s son Donald often echoes his father’s white-supremacist leanings and Madison Grant’s racist, Nazi-inspiring rhetoric. In the first speech of his 2016 presidential campaign, the one he made after descending the elevator in Trump Tower like a self-selected savior sent down from on high, he famously ranted that Mexican immigrants are “bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.” Yeah, right.

Trump has gone on and on about immigrants “poisoning the blood of our country.” Then he and fawning understudy JD Vance gleefully repeated the lie about Springfield, Ohio, Haitians — Black as well as immigrant, you know — eating real Americans’ cats and dogs.

Given Trump’s studied ignorance, he likely has little idea who Madison Grant was, yet he channels the same racist leitmotif of division and hate that propels The Passing of the Great Race and won Hitler’s admiration. And the president-elect’s calls for mass deportations backed by borderlands camps and military round-ups sound altogether too much like the anti-Jewish cleansing of Nazi Germany and those long trains of packed cattle cars steaming into Auschwitz.

History doesn’t repeat, yet it does rhyme. That’s what we’re hearing now, a disturbing contemporary resonance with a dark chapter in this nation’s past. High time to recognize it for what it is, call it aloud by its true name, and make ready to come together and resist.

Update: U.S. boarding schools killed even more tribal students than previously reported

According to the Dept. of the Interior’s ground-breaking report of the harm done by so-called Indian boarding schools, 973 students died while enrolled. A recent Washington Post investigation revealed the actual toll to be more than 3,000. To learn more about the scope of this horror, check out the PBS Evening News interview with lead reporter Dana Hedgpeth (Haliwa-Saponi Tribe of North Carolina) on the Post’s investigation.

Cast out of Eden heads to Martinez, Calif., next week

On Wednesday, Jan. 8, 2025, 5 p.m., I’ll be talking about the book to the Martinez Rotary Club. It’s a fitting venue: John Muir spent the last three decades of his life in Martinez and made a sizable fortune in the local orchard business. The event will held at the Martinez Campbell Theater, 636 Ward St. in downtown Martinez, and it is free and open to all. No advance reservations needed.