Where "Cast out of Eden" Came From

How a chance discovery on one book led me to write quite another

When I was researching my previous book, The Modoc War, I happened quite by chance on the fact that John Muir visited northeastern California’s Lava Beds to have a look at the battleground for himself.

He came a little more than a year after the last shots were fired, four Modoc leaders were hanged for war crimes — the only Native Americans ever tried on such charges — and the surviving insurgents were exiled to impoverished, often-lethal misery on an Oklahoma reservation. What stood out about this little-known, post-war visit was Muir’s striking reaction to the landscape — and its former inhabitants.

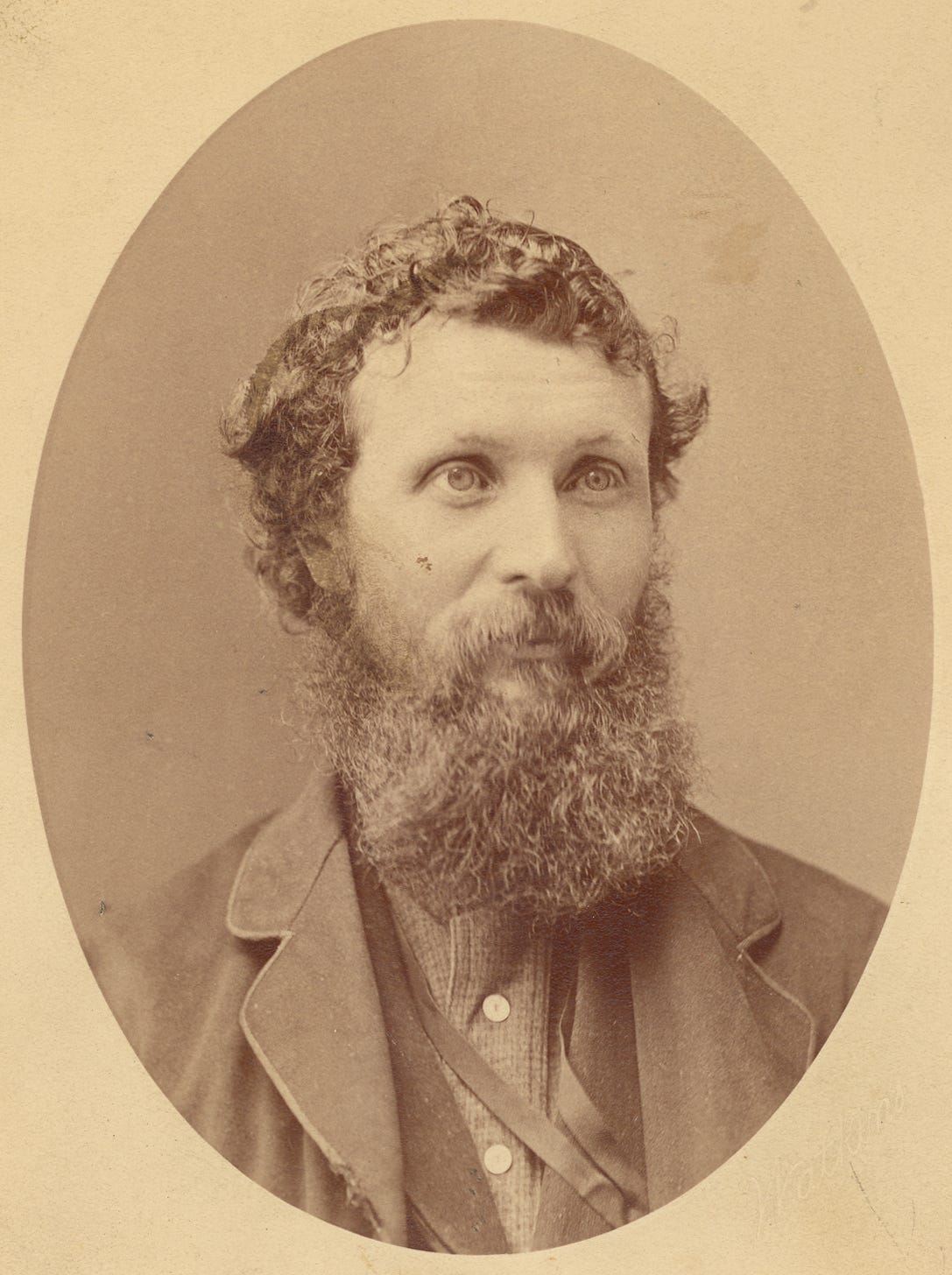

It happened in the twilight of an early December evening in 1874. A lean, lanky, 36-year-old Muir stepped away from his companions at the campfire to take in the view from a high point on the ridge overlooking the Lava Beds. I, too, have stood in that selfsame spot, the better part of a century and a half later, and marveled at the grandeur Muir took in.

To his left on the north, Tule Lake stretched in a giant sheet up into Oregon, its stillness slowly purpling as the light faded. To the right and south, uncut forests of old-growth yellow pine softened the contours of the volcanic enormity known as the Medicine Lake Highland. Straight ahead, on the eastern horizon, the first snows capped the far-off peaks of the South Warner Range.

Yet Muir felt none of the elation I experienced at this panorama. Rather, something dark welled up in him. Unlike any other wild space before or after, this one creeped him out.

Try as he might, Muir could not take his eyes off the Lava Beds just below.

“Here you trace yawning fissures, there clusters of somber pits; now you mark where the lava is bent and corrugated into swelling ridges. Tufts of grass grow here and there, and bushes of the hardy sage, but they have a singed appearance and do not hide the blackness. Deserts are charming to those who know how to see them — all kinds of bogs, barrens, and heathy moors, but the Modoc lava beds have for me an uncanny look. The sun-purple slowly deepened over all the landscape, then darkness fell like a death, and I crept back to the blaze of the camp-fire.”

As the flames held back the night, Muir had to be mulling over his strange reaction to this wild place. He had just devoted the better part of five years to living in Yosemite Valley, making long solo hikes into the Sierra Nevada’s granite grandeur, and extolling in his journals and newspaper accounts the infinite peace and myriad blessings of the high and the sublime. Yet here he was, at the wild edge of just such a space, feeling his skin goosebump and his spine shiver. He must have been wondering why.

Muir got the answer the next morning, when he and his companions descended the ridge onto the Lava Beds. There the naturalist recognized that his dread was rooted less in the volcanic terrain’s strangeness than in the human drama that had played out here. The rock walls of a military graveyard at the foot of the ridge enclosed the bodies of thirty U. S. Army soldiers “surprised by the Modocs while eating lunch, scattered in the lava beds, and shot down like bewildered sheep.” Those buried battlefield casualties had cast the deathly pall Muir felt the evening before.

Aware from ubiquitous and lurid newspaper accounts of the wartime horror on the Lava Beds, Muir easily imagined the terror soldiers felt in this battlefield where uplifted black rock twisted into “the most complete natural Gibraltar I ever saw.” Modoc riflemen in well-chosen sniping positions picked off advancing infantry from cover so perfect that return fire only wasted powder and lead.

“They were familiar with by-ways both over and under ground, and could at any time sink out of sight like squirrels among bowlders. Our bewildered soldiers heard and felt them shooting, now before them, now behind them, as they glided from place to place … all the while maintaining a more perfect invisibility than that of modern ghosts.

“Modocs, like most other Indians, are about as unknightly as possible. The quantity of the moral sentiment developed in them seems infinitely small, and though in battle they appear incapable of feeling any distinction between men and beasts, even their savageness lacks fullness and cordiality. The few that have come under my own observation had something repellent in their aspects, even when their features were in sunshine and settled in the calm of peace; when, therefore, they were crawling stealthily in these gloomy caves, in and out on all fours, unkempt and begrimed and with the glare of war in their eyes, they must have looked very devilish.”

As Muir saw it, the Modocs had opted for infernal savagery over the civilization promised in America’s inexorable advance. The deep chill he felt on the Lava Beds overlook rose from this close brush with something primitive, atavistic, even demonic.

Which got me wondering: Was the Lava Beds experience a one-of-a-kind for Muir, or did it typify his perspective on Indigenous peoples? Answering that question over the next four years led to Cast out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness.

In the four decades following Muir’s trip to the Lava Beds, his writings and public advocacy built a worldview where wilderness offered a sanctuary for humans — of the white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant persuasion, of course — to fully experience their spiritual essence. Native Americans sullied the pure wilderness where civilized Euro-Americans could marvel at the ongoing miracle of Eden before serpent and apple made a mess of paradise.

“Most Indians I have seen are not a whit more natural in their lives than we civilized whites. Perhaps if I knew them better I should like them better. The worst thing about them is their uncleanliness. Nothing truly wild is unclean.”

Muir hardly invented this point of view. Rather, he reflected, channeled, and rarefied thinking that arose in Europe, flowered in a United States filling with immigrants, and cloaked Anglo-Saxon Protestant supremacy in fake science. Manifest Destiny necessitated the conquest and dispossession of Native Americans; Muir extended this ideology to the continent’s wildest reaches.

And how that happened, and what it means even now, is the story Cast out of Eden tells.

Pre-order at a Discount

Cast out of Eden publishes on May 1. Order a copy now for delivery on the publication date, and you’ll save 40% off the cover price. All you have to do is use discount code 6AS24 at the University of Nebraska Press website. Thanks!

Full of early California history after a fast start, thoughtful mid and excellent closing! Macnally’s finish as a woodsman himself is gratifying to learn.

Racism is a powerful drug, isn't it? It's chilling to see Muir, such a keen observer of the natural world, be absolutely incapable of seeing the humanity of native people. Excited to read the book. You are such a beautiful writer!