Wilderness Influencer

With a little help from his friends, John Muir pitched national parks as wild sanctuaries for spiritually starved Americans. It proved a great PR strategy.

The campaign to preserve Yosemite earned Muir his reputation as father of the national parks. Yet the idea wasn’t Muir’s, at least not in the beginning. That honor falls to Robert Underwood Johnson.

As associate editor of The Century Magazine, Johnson prided himself on sensing the quickening pulse of emerging social and political trends and making the acquaintance of the people who shaped them. His formula worked. The Century grew into a high-circulation, high-end media success, publishing fiction by such Gilded Age luminaries as Mark Twain, Kate Chopin, and Bret Harte and curating pictorially rich feature series, including reminiscences by decorated generals on both sides of the Civil War.

The success of those Civil War stories brought Johnson to San Francisco; he had sold editor-in-chief Richard Gilder on a similar series focused on California gold rush pioneers. While he was in town, he wanted to meet one of The Century’s now-and-then writers in person and encourage him to submit more articles. John Muir, glad to get away from the drudgery of his orchard business across the bay, accepted Johnson’s invitation to dine at downtown San Francisco’s elegant Palace Hotel.

The two men, who shared a love for mountains and woods, took to each other before they finished the soup course. By the time dessert came, they had hatched a getaway plan. Once Johnson wrapped up his gold rush interviews, he and Muir would escape to Yosemite Valley and the Sierra Nevada high country. With a wrangler cum cook named Pike and three anonymous burros carrying food and gear, the two newly fast friends hiked out of the valley to Tuolomne Meadows and camped at Soda Springs. In the evenings they hung around the fire to swap stories, and through the days they sauntered among the peaks and meadows.

Johnson admired Muir’s easy way of skimming over smooth terrain and leaping from rock to rock with a bighorn’s springy certainty. “A trick of easy locomotion learned from the Indians,”Johnson declared, which it surely wasn’t. Still, the journalist saw something else in Muir that convinced him of the workability of the plan he was pulling together. “In the wilderness Muir looked like John the Baptist, as portrayed by Donatello,” Johnson declared, and that was a good thing.

In the campfire’s dancing light, he laid out what he had in mind. Like Muir, Johnson was an advocate for saving spectacular wild lands from capitalist exploitation. He backed a legislative proposal to create a Yellowstone-like Yosemite National Park that would surround Yosemite Valley — run by the state of California at the time — and protect a significant reach of the Sierra Nevada as well.

Tuolomne Meadows offered Johnson and Muir graphic evidence for why such a solution was needed. Numerous flocks of sheep driven — by immigrant Portuguese herders, Johnson made clear — into the once chest-high meadows each summer ate everything green down to the roots. Muir despised sheep as “hoofed locusts,” and like Johnson he wanted them gone.

Knowing that stock grazing would be banned in a national park, Johnson made Muir an offer he couldn’t refuse: if Muir would write two articles, one on “The Treasures of the Yosemite,” describing the valley’s wonders, and the other on “Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park,” outlining the reserve’s boundaries and explaining its wild rationale, Johnson would convince his editor-in-chief to run them. Then he himself would put the published pieces before the U. S. Congress’s Committee on Public Lands to help push the Yosemite National Park proposal forward. Johnson enjoyed personal relationships with key politicians in Congress, and he felt certain that the publicity campaign would make a national park politically possible. Muir signed on.

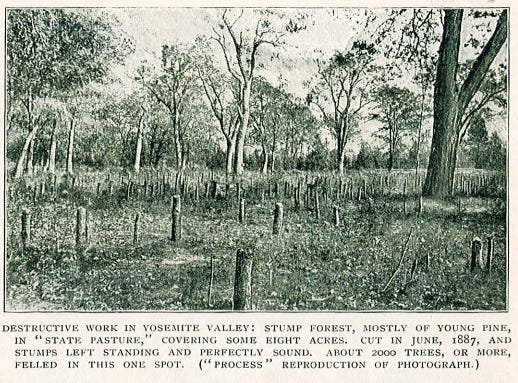

He completed the articles, as ever a painfully slow process of writing and revising again and again over several months, and The Century ran them with its characteristic, finely detailed illustrations. “The Treasures of the Yosemite” appeared first, in August 1890. Muir spelled out the core threat: “In Yosemite, even under the protection of the Government, all that is perishable is vanishing apace.” Two illustrations, one of a meadow plowed up to grow hay and another of a forest of young pines slashed to stumps, underscored that destruction.

The loss would be unimaginable, Muir wrote:

No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite … as if into this one mountain mansion Nature had gathered her choicest treasures, whether great or small, to draw her lovers into close and confiding communion with her.

Muir enlarged his praise song and plea with “Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park” in the The Century’s September issue. Yosemite amounted to more than just the valley; it belonged to a wider region of wonder:

Most people who visit Yosemite are apt to regard it as an exceptional creation, the only valley of its kind in the world. But nothing in Nature stands alone. She is not so poor as to have only one of anything.

The less-known Hetch Hetchy Valley rivaled Yosemite for granite monoliths and spectacular waterfalls. And it was but one of many miracles to be savored within the proposed park. The entire landscape, outlined in detail by a map that showed how the national park would embrace the valley, deserved federal attention.

The threat was clear:

Unless reserved or protected, the whole region will soon or late be devastated by lumbermen or sheepmen, and so of course made unfit for use as a pleasure ground…. Ax and plow, hogs and horses, have long been and are still busy in Yosemite’s gardens and groves. All that is accessible and destructible is being destroyed

As for the Indigenous peoples who had lived in the area for millennia and continued to people what would be the park, Muir paid them little mind. He dropped a few of their place names to add local color and turn the tribes into the relics of a fast-fading past. Manifest Destiny had conquered them, lumbermen and sheepmen filled the void, and now was the time to chase out loggers and herders and raise Yosemite to its highest and best use: as a contemplative pleasure ground for Euro-American tourists and nature lovers.

With Muir’s articles in hand, Johnson appeared before the House committee overseeing the Yosemite National Park bill. His timing was fortuitous. Even though the committee’s members had no idea who John Muir himself was, they had heard about Muir Glacier in Glacier Bay. Remarkably, landmark status proved endorsement enough. With surprising unanimity the committee agreed to the national park idea and moved it forward. Soon the proposal and the amount of land it preserved grew to the capacious boundaries Muir proposed. Once the bill passed both houses of Congress, President Benjamin Harrison signed it into law on October 1, 1890.

Johnson and Muir were cresting a wave: after two decades of debate about the destruction of public resources for private profit, Congress was embarking on a wild-lands tear. Just a few days before Harrison signed the Yosemite bill, he put his signature on another law that established Sequoia National Park in the Southern Sierra. The Yosemite law also contained provisions that set aside General Grant National Park, which protected many of the giant sequoia groves and would be enlarged into King’s Canyon National Park in 1940. The following spring, President Harrison signed the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, which granted the president executive authority to protect watersheds and timber.

Muir’s prophetic appearance on the wild-lands scene at Johnson’s prompting had scored success farther and faster than either would have thought possible back at their Soda Springs campfire. The new national parks in the Sierra Nevada delivered another payoff as well: now the army could drive out the unwanted, including the tribes. Yosemite would become the protected fortress its survival required.

Next up: the troops hit the high country.

Cast out of Eden hits Berkeley this Sunday …

On Sunday, Sept. 29, 12:45 p.m., I'll be talking about the book, John Muir, and the foundations of the national park system in person at Berkeley Society of Friends, in person at 2151 Vine St. (near Shattuck), Berkeley, CA 94709. Free and open to all.

then Orinda next Saturday …

On Saturday, Oct. 5, 2 p.m., I’ll be on the other side of the Caldecott Tunnel at Orinda Books, reading from Cast out of Eden, answering questions and comments, and signing copies in-person, 276 Village Square, Orinda, CA 94563. Free and open to all; please register in advance at Eventbrite.

and comes to C-SPAN Book TV this weekend.

My July 24 Commonwealth Club conversation with Andrew Dudley of the Earth Live independent media network about the book airs twice this weekend. You’ll find the times and channels here. Thereafter, the broadcast will be available online as part of C-SPAN’s American History TV series. I’ll post that link as soon as it’s available.