Yosemite’s Genocidal Backstory, Part One

Now it’s cars in long lines and tourists in sunburned throngs. Back in the day, the valley’s granite grandeur became a killing field.

If it hadn’t been for the California genocide, white people wouldn’t have “discovered” Yosemite Valley when they did. It all had to do with a series of unfortunate events in Mariposa County.

Lured by the sparkle of Mariposa’s goldfields, miners, ranchers, farmers, traders, and market hunters overran the area in the late 1840s and early 1850s and ravaged it. Mining waste trashed rivers and their tributaries, deer and elk disappeared from forests and meadows, and loosed hogs rooted up the oak groves the local tribes relied on for the acorns central to their diet. Retreating into the high country to avoid deadly encounters with armed settlers and struggling to feed themselves, various tribal bands turned to stealing horses, mules, and cattle for food. Now and again, confrontations with Euro-Americans over livestock turned deadly. The rumor mill blew these stories into torture porn worthy of the most lurid dime novels.

As anti-Indigenous panic rose with each new salaciously invented atrocity, the Mariposa County sheriff raised a large posse in early 1851 and led an attack on a village occupied by several tribes gathered for a religious ritual. The posse employed a tactic standard for village raids. Before dawn, riflemen surrounded the encampment. As the sun rose, they fired repeated volleys into the village, and then, when the guns’ barrels fouled with black powder residue, they charged with pistols, knives, and hatchets for killing up-close and personal. The posse claimed that it took out between 40 and 50 warriors, and then burned huts and food stores, losing only two dead and four wounded, more likely by friendly fire than by bows, arrows, and spears.

When the smoke cleared, the sheriff sent off a letter asking the state to fund his vigilantes. In short order, the sheriff was authorized to raise a force of 200 paid for by the state.

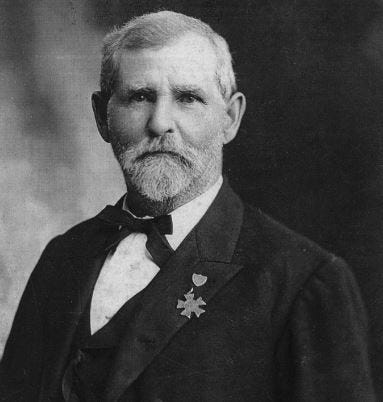

Among the men recruited into the Mariposa Battalion was Lafayette Bunnell, a 27-year-old eager to protect his neighbors, admirably “hardy, resolute pioneers” in his eyes. Bunnell’s motivation was less than entirely altruistic; he stood to make good money running the tribes to ground. The pay scale from private to major ranged from $5 to $15 a day, equaling or bettering what a man could make at the much harder work of mining.

Chosen to lead Bunnell and the Mariposa Battalion was James Savage, a shadowy character who — as writer Rebecca Solnit proposes — could have played Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Savage ran a string of trading posts in the San Joaquin Valley and Sierra foothills, worked mines with virtually enslaved Native Americans, took wives from several tribes as insurance against retribution, and happily used violence against anyone, particularly uppity tribal people, who got in his way. As grandiose as he was greedily brutal, Savage crowned himself “el rey tulareño,” king of the Tulares.

Savage’s wives told him that nearby tribes were banding together to drive out the invading miners. Nothing frightened settlers as much as the prospect of a general Indigenous uprising. Savage himself became a target when an attack on his Fresno River trading post killed three clerks and cost him all his trade goods. He resolved to crush the rebellion and restore his profitable alpha-dog dominance.

Bunnell fell under Savage’s spell, depicting him as a frontier superhero who had walked out of a James Fenimore Cooper novel — the time’s equivalent of Marvel Comics — into real life:

No dog can follow a trail like he can. No horse endure half so much. He sleeps but little, can go days without food, and can run a hundred miles in a day and night over the mountains and laugh for hours over a camp-fire as fresh and lively as if he had just been taking a little walk for exercise.

One rumor making the Mariposa County rounds had it that a band of particularly egregious horse thieves occupied a mountainous hidey-hole far up the Merced River. Summoned by an envoy, the band’s headman, Tenaya, and some of his people arrived at the battalion’s camp to tell Savage that they had everything they needed in their ancestral home and no interest at all in moving to the hot, dry Fresno River reservation where Savage wanted to send them. Unswayed, Savage resolved to take a portion of his force, force Tenaya to act as unwilling guide, and climb to the deep valley where the tribe lived, round up the entire band, and drive them down to Fresno River. And so the Mariposa Battalion became the first Euro-Americans to enter what is now known as Yosemite Valley.

The sight of the valley from a high point sent Bunnell into seraphic transport. He exclaimed:

I have here seen the power and glory of a Supreme being; the majesty of His handy-work is in that “Testimony of the Rocks.”

Bunnell wanted to memorialize the “discovery” of this divine place with a name suitable to its godly grandeur. In fact, it already had a name — Ahwahnee — and it had been peopled for nearly six millennia. In the last decade of the 18th century, some unnamed plague, likely brought by soldiers and missionaries from Mexico and carried along tribal trade routes, swept through Ahwahnee and killed about one-third of the people then known as Ahwahneechees. Fearing that the pestilence arose from the valley itself, the survivors fled over the Sierra crest to the Mono Lake domain of the Kutzadika’as, with whom they had long been trading partners. Tenaya was born there, the son of an Ahwahneechee chief and a Kutzadika’a mother.

When he grew to early manhood, Tenaya and a number of Ahwahneechees returned to the valley sometime between 1805 and 1820 to reclaim their birthright. They welcomed refugees from other Miwok groups, Kutzadika’as, Monaches from the upper elevations of the western foothills, Yokuts from the Central Valley, and neophytes of various tribes on the run from the missions and their forced labor. These people called themselves Yosemites, a name Bunnell thought meant “grizzly bears” in the Miwok tongue. His etymology was mistaken; the word means “those who kill” and referred not to the place but the people’s reputation for toughness. Despite the mistranslation, Bunnell’s name for the valley stuck.

By replacing the name Ahwahnee with a moniker of his own selection, Bunnell made a seeming bow to the place’s Indigenous reality while turning its long-term occupants into something nostalgic, something sure to vanish into history’s fading mists before Manifest Destiny’s unstoppable advance. His name mean to erase the Yosemites as a people.

As soon as the Yosemites knew that Bunnell, Savage, and the Mariposa Battalion had entered the valley, they fled. Only one old woman remained behind, according to Bunnell, too aged to climb the rocky, precipitous trail and escape. He likened her to a “vivified Egyptian mummy. This creature exhibited no expression of alarm, and was apparently indifferent to hope or fear, love or hate.” Bunnell saw her as subhuman, a primitive throwback, “a peculiar living ethnological curiosity.” Savage tried to get her to tell him where the rest of her tribe had gone, but the old woman gave him nothing more than a knowing, catch-them-if-you-can smile. Bunnell did not record what became of her.

Almost certainly it went badly. The invasion in 1851 “was a massacre,” Della Hern, a tribal elder and basket weaver, told a Mariposa Gazette & Miner reporter 136 years later. She had not been there, of course, but her great-grandfather, whom Euro-Americans nicknamed Captain Sam, and his family had been, and they passed their firsthand story down to their descendants.

As they told it, news of the approaching militia had panicked the Yosemites. Knowing full well Euro-American violence and weaponry, the Yosemites packed up what they could and dashed eastward into the High Sierra. Sam’s two daughters were too little to travel so far so fast, and his parents too old, so he hid the foursome in the rocks and warned them not to move a muscle. True to type, the militiamen rampaged through the empty village and hunted down anyone who stayed. The two little girls escaped detection, but the raiders rooted out the elderly pair. The miners-turned-militiamen looped ropes around their necks and over a tree limb then hoisted their frail, struggling bodies aloft. They were hanging there still when Sam and the rest of the family returned.

Since the militiamen had neither the time nor the supplies to pursue the escaping Yosemites into the high country, Savage ordered his men to burn huts and food caches, destroying shelter and sustenance even as a snowstorm approached. Then the battalion headed back toward Mariposa, planning to convey Tenaya and the captured members of his band to the Fresno River reservation. The headman had the last laugh, however. In the middle of the night he and his people slipped away undetected and hightailed it for home.

The Mariposa Battalion was not done, however. Soon they would return.

Upcoming Events

On Saturday, Aug. 10, 7 p.m. PDT, I’ll be reading from Cast out of Eden, talking about the book with poet and writer Moira Mattingly, and taking questions from the audience at The Bookery, 326 Main St., Placerville, CA. Free and open to all.

The following Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2 p.m. PDT, I’ll be talking about the book and taking audience Q&A under the auspices of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at California State University East Bay, Concord Campus, 4700 Ygnacio Valley Rd., Concord CA. You can register here.