The Company He Kept: The Editor-Friend Who Saw Natives As “Actual Humans”

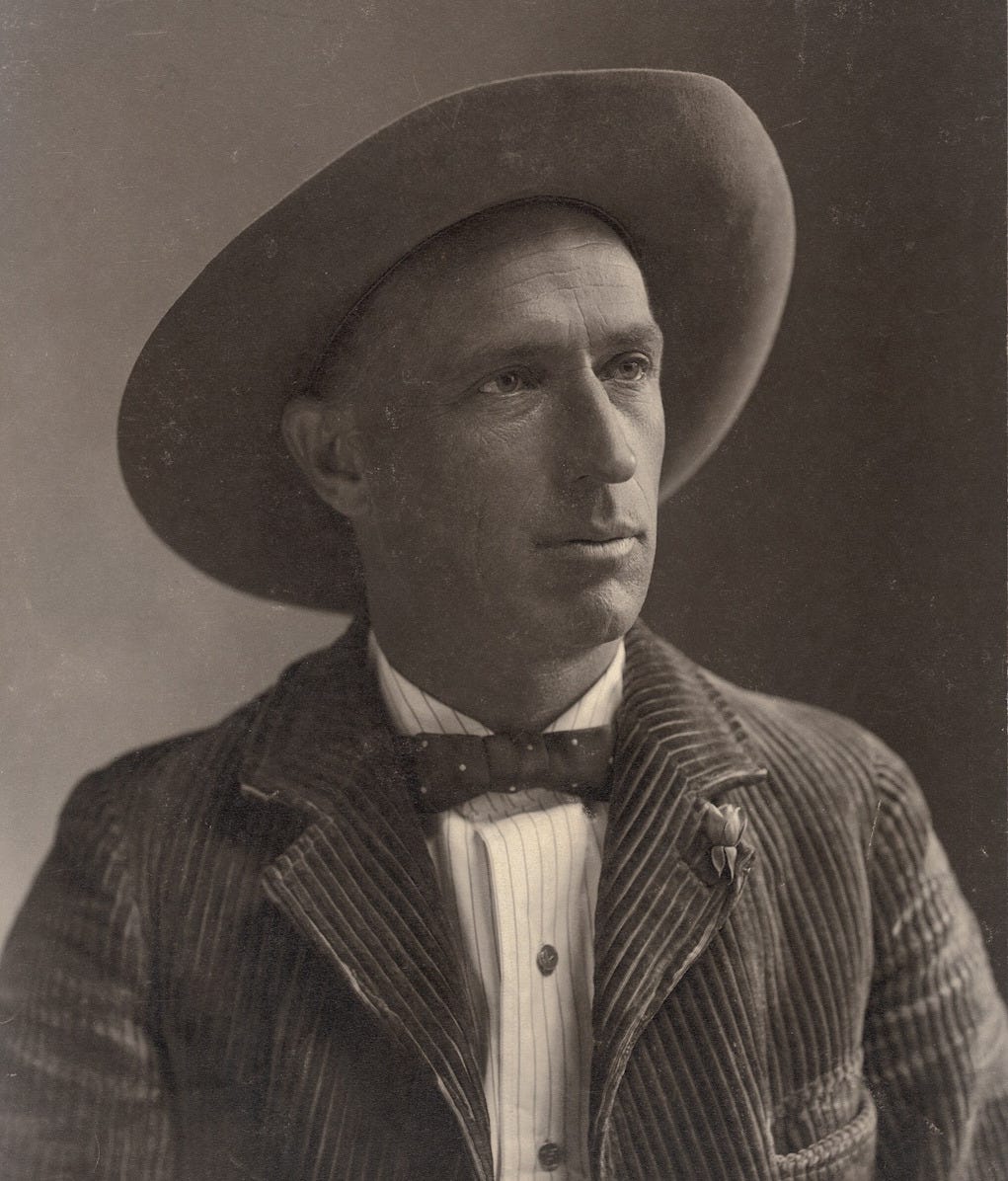

Like Muir, Charles Fletcher Lummis began his career by walking a long way, then writing a book about it.

As a young, eager man, Muir hoofed it from Kentucky to the Florida Panhandle and told the tale in A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. Likewise young and equally eager, Lummis set off on a loopy walkabout from Chillicothe, Ohio, to Los Angeles — approximately 3,500 miles by his idiosyncratic route — to take up the job he’d been offered as the Los Angeles Times’ first city editor, a journey he detailed in A Tramp Across the Continent.

The two men came to know each other when Lummis took over a Southern California–based promotional magazine that became the influential Out West. He steered the publication in a new, literary direction by soliciting articles from notable western writers, including Muir. In addition to magazine work, the two men shared an ongoing correspondence about their children, the campaign to stop the Hetch Hetchy dam, and backcountry excursions.

Lummis and Muir also shared a connection with Theodore Roosevelt. Lummis had been Roosevelt’s classmate at Harvard before he dropped out of college, and he maintained the friendship for years after. Muir and Roosevelt camped together in Yosemite in summer 1903 and corresponded until the politics of the Hetch Hetchy dam proposal pushed them apart.

Muir, Lummis, Roosevelt thought somewhat alike. All three saw civilization as a force that drained men of their virility and had to be countered by manly pursuits like hunting, wilderness camping, and long-range backcountry saunters. None of them welcomed the surge of immigrants pouring into the United States from Southern and Eastern Europe, and they were all concerned that America’s white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant root stock would be swamped out by fertile Jewish and Catholic foreigners. None ever became as extreme in their thinking as Henry Fairfield Osborn and Madison Grant, yet they did sing from a harmonious hymnal.

Lummis, though, differed on an important issue: Native Americans. He saw them as an significant element in the West’s complex cultural mosaic, recognized the injustice they had been subjected to, and he took steps to remedy it.

This revelation came to Lummis when he was residing in the Pueblo of Isleta (Shiewhibak), a Tiwa community in the Rio Grande Valley south of Albuquerque. He had retreated to New Mexico from Los Angeles to recover from partial paralysis brought on by a stroke at the age of only 29.

The move proved salutary:

I have lived now in Isleta for four years, with its Indians my only neighbors; and better neighbors I never had and never want. They are unmeddlesome but kindly, thoughtful, and loyal, and wonderfully interesting.

He praised “their endless and beautiful folklore, their quaint and astonishing costumes, and their startling ceremonials.” Lummis later invited his Tiwa neighbors to perform at fiestas he organized in Los Angeles, and he advocated for two nearby tribes when they were forced off their San Diego homeland.

Warner Ranch, known now as Warner Springs, had been the territory of the Cupeños (Kuupangaxwichem) and Diegueños (Kumeyaay) peoples for centuries. When two prominent Californians acquired much of the land, they saw the Indigenous people as squatters and wanted them gone. After a decade-long legal battle that climbed the judicial ladder, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Cupeños and Diegueños had no legal right to the land and forced them to give up their homes.

Seeing the ruling as unjust dispossession, Lummis formed the Sequoyah League to provide the two tribes with a new homeland. He attracted to his cause such luminaries as David Starr Jordan of Stanford University, Glacier National Park advocate and Forest and Stream editor George Bird Grinnell, and United States Biological Survey head C. Hart Merriam. Muir, too, joined the league, paying membership dues for himself and daughter Helen and lauding Lummis for “the noble work you are doing for our fellow mortals.” As a result of his advocacy, Lummis was named to the federal commission that eventually located a reservation for the Warner Ranch tribes in the Pala Valley and acquired it for a little over $46,000 in Interior Department funds.

Lummis’s attitude toward Native Americans was paternalistic, for sure; the Sequoyah League’s motto was “To Make Better Indians,” a phrase fairly dripping noblesse oblige. Still, he respected Indigenous cultures as complete within themselves, and he opposed forced-assimilation strategies like the Carlisle Indian School, which stripped Native American children of language, culture, and long hair. Carlisle embodied founder Richard Henry Pratt’s strategy to ensure “that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Carlisle and boarding schools like it, Lummis argued, severed Indigenous children from their cultural roots and family ties and consigned them to the lowest rung of the Euro-American world.

When Theodore Roosevelt won the presidential election in 1902, Lummis sent his former Harvard classmate a congratulatory letter holding out hope that, for once, the administration would field a competent Office of Indian Affairs. “I care for Indians not as ‘bric-a-bac’ but as actual humans,” he explained.

Unfortunately, Lummis’s favorable take on the value of Native American ways and on the injustice of pushing tribes off their long-held homelands influenced Muir little beyond his nominal Sequoyah League membership. In his view, scenic landscape was all, and contemplation by spiritually sensitive men of his own background and bent constituted its highest use. Indigenous people just cluttered up the viewshed. On that count Lummis never swayed Muir’s made-up mind.

Up next: The physician turned wildlife scientist turned anthropologist of Native California.

Cast out of Eden in Martinez

On Thursday, Jan. 30, 12:15 p.m., I’ll be talking to Rotary of Pleasant Hill about the book and John Muir. The event will be held at the Campbell Theater, 636 Ward St., Martinez, Calif., just a few miles down the road from the home where Muir lived for the last 30 years of his life. Lunch is served at this gathering, so please RSVP to Jocelyn Reite at info@thereiteco.com.