The Company He Kept: The Wildlife Scientist Turned Native California Anthropologist

C. Hart Merriam brought his field-science skills to bear on the state’s tribal peoples.

In summer 1871, when John Muir was a 33-year-old living in Yosemite and making pocket money by showing tourists the valley’s sights and spectacles, he took on Clinton L. Merriam as a client. The naturalist soon learned that Merriam was a man of some standing, a former Wall Street broker who had turned his financial success into a seat in the House of Representatives. Merriam’s political career, however, interested Muir far less than the New Yorker’s enthusiasm for geology. The naturalist took extra time to explain in detail to the politician how glaciers had shaped the extraordinary valley whose scenic wonders they were now taking in.

After Merriam went back east, he and Muir corresponded. Impressed with the naturalist’s self-taught expertise, Merriam asked whether Muir would consider a scientific posting to the Smithsonian or some similar institution. After years of studying on his own and glomming onto practically any paying job that came his way, Muir was ready for a change from this patchwork life. He wrote back:

I answer, Yes. If I could give my whole time to science, I should be happy indeed, and no amount of hardship and labor could crush or outweary me. I should like to collect plants or minerals or insects or to prepare a work upon the trees of this coast, or to take part in any exploring expedition in which there was work that I was capable of doing.

Twenty-eight years later, Merriam’s son, C. Hart Merriam, recalled what his father had to say about meeting Muir back in the day. Merriam was finishing up an unusual task that had come to him as head of the Department of Agriculture’s Division of Biological Survey. Railroad magnate E. H. Harriman approached Merriam in his quest to turn an Alaska bear-hunting jaunt into a proper scientific expedition. He made Merriam an offer too good to refuse: the tycoon wanted to invite along a select group of senior scientists — all expenses paid, of course — for this voyage into the far north. Merriam agreed to come along and to choose the scientists, and so it was that he invited John Muir to join the 1899 Harriman Alaska Expedition as its glaciologist.

In the course of the voyage, Merriam and Muir recognized each other as enthusiastic naturalists and soon became good friends. The following summer, they teamed up for a long trip through Muir’s old mountain haunts, crossing back and forth over the spine of the Sierra Nevada four times. Afterward they kept up a correspondence that included Christmas packages of fruits and nuts from Muir’s Martinez orchard. Merriam also pitched in to help Muir in his fight to stop the Hetch Hetchy dam project.

That fight was still going on in 1910 when, Mary W. Harriman, E. H. Harriman’s widow and heir and the richest woman in America, offered to fund Merriam’s research, no matter what he worked on, through the Smithsonian’s E. H. Harriman Fund — an offer something like a contemporary McArthur Genius Grant. Harriman assumed that Merriam would keep researching birds and mammals as he had for decades. What Harriman didn’t realize was that Merriam was becoming more and more interested in investigating the long-overlooked Native Californians.

Grasping this rare chance for a midlife career change, Merriam signed on to Harriman’s financial arrangement, resigned from the Biological Survey, and launched in-depth field studies of Native California’s peoples, cultures, and languages. The institutional irony was rich: even as Harriman money was funding the fast-growing, white-supremacist eugenics movement, it was supporting Merriam’s research on, and advocacy for, Native Californians.

Merriam’s extensive field work up, down, and across the state led him to realize that Native Californians were far more intelligent and adept than Euro-Americans gave them credit for. Merriam grew to hate the slur “Digger,” and he held that tribal nations should be called by the names they gave themselves, not by somebody else’s inaccurate, even nasty handle. He recognized that “squaw” to a Native woman was as offensive as “skank” or “slut” to a Euro-American. He came to argue, as did C. E. Kelsey, that California’s tribal nations had been terribly wronged by American conquest and deserved compensation for the land stolen from them:

Great injustice has been done the Indians of California in that we have confiscated their lands, driven them into remote and inhospitable parts of the State, deprived them of their natural food, imprisoned them for killing deer or taking fish, inoculated them with fatal diseases, and, for a period of at least fifteen years (1849–1864), we hunted and shot them down by hundreds.

Further, Euro-Americans could take more than a few lessons from Indigenous peoples:

We have as much to learn from them as they from us, but nevertheless, and entirely apart from their superior knowledge of the food, textile, and medicinal values of animals and plants, they can put us to shame in matters of patience, fairness, honor, and kindness.

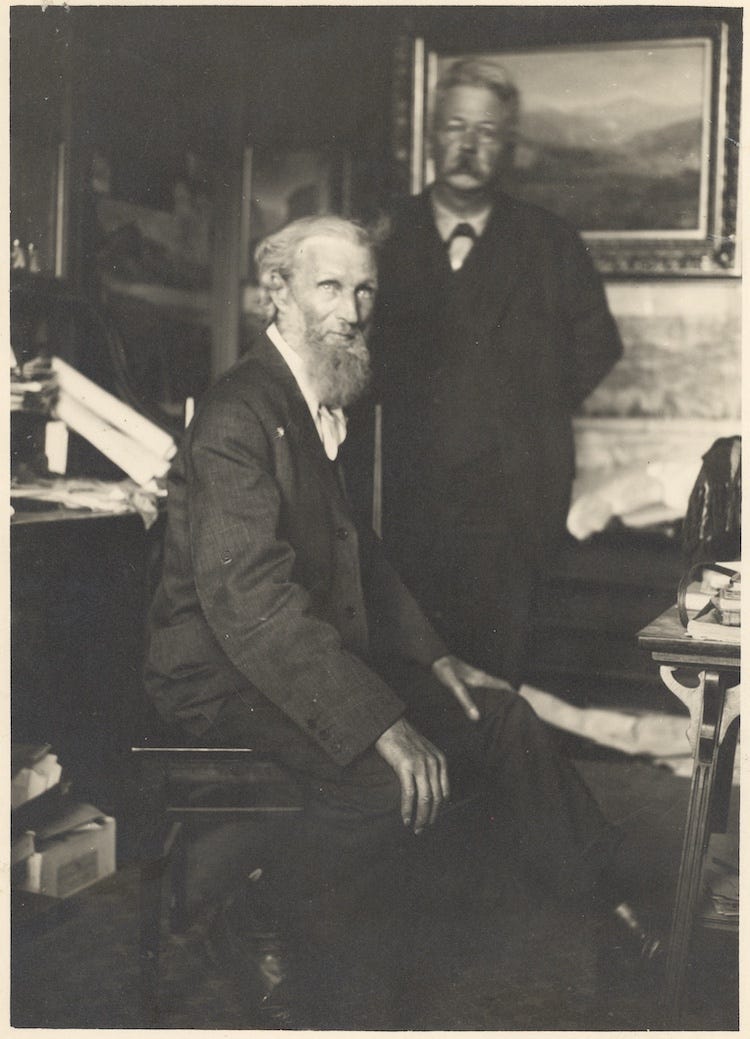

Up next: Merriam took the only known photo of Muir with Indigenous people.

Cast out of Eden in Martinez

On Thursday, Jan. 30, 12:15 p.m., I’ll be talking to Rotary of Pleasant Hill about the book. The event will be held at the Campbell Theater, 636 Ward St., Martinez, Calif., just a few miles down the road from the home where Muir lived for the last 30 years of his life. Lunch is served at this gathering, so if you wish to attend, please RSVP to Jocelyn Reite at info@thereiteco.com.

You can really see that Muir is not well in that last photo... Thank you for sharing!