The Fellow Wisconsin Badger Who Saw Native Peoples Differently

Yes, John Muir lived in a white-supremacist time. But not everybody signed on.

Presentism is the term historians use: judging the people of the past by the standards of the present. While researching and writing Cast out of Eden, I grew concerned about falling into the presentism trap on John Muir. After all, his was a deeply racist era. So, were Muir’s writings merely another example of unquestioned and prevailing attitudes for which he bore no responsibility? Or were Muir’s choices concerning even in the context of his time?

For an answer on how to make that judgment, I turned to Jeffrey Ostler, professor emeritus of history at the Univ. of Oregon and the author of Surviving Genocide, a chilling history of the horrors that befell Native America between the American Revolution in 1776 and Bleeding Kansas of the 1850s. Since genocide is itself a 20th-century concept, I wanted to ask Ostler how he avoided presentism in writing this dismal story.

Over the phone, he gave me an excellent method of evaluation: seek out people who lived at the same time as the subject yet had different points of view. If such folks turn up, then the subject’s choices are their individual responsibility, not simply the inescapable echos of the era.

With that framing in mind, I researched the people in Muir’s orbit with an eye to their attitudes toward Native Americans. Some, such as Joseph C. LeConte, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Madison Grant, were unabashed white supremacists who dismissed Natives as a lesser race of little worth and less concern. Yet others, three in particular, grasped the full humanity of Indigenous peoples and advocated for them.

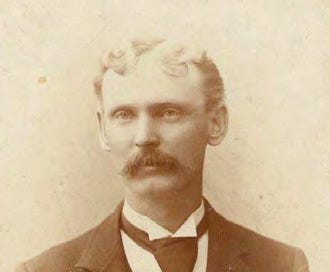

As far as I can tell, Muir never met C. E. Kelsey, yet the two men shared childhoods in Wisconsin, studies at the University of Wisconsin, and professional lives in Northern California. Kelsey earned his law degree in Madison and then, like Muir, made his way west, settling in San Jose and opening a legal practice. San Jose was also home base for the Northern California Indian Association, a non-denominational Christian organization focused on the state’s many landless tribes. Kelsey had gained experience with tribal issues from working as a clerk at the Green Bay Indian Agency before law school, and he wanted to use his legal expertise to the tribes’ benefit. Joining NCIA and soon becoming a leader, Kelsey ran the organization’s campaign to lobby Congress for laws supporting Native Californians who lived off reservation.

The land situation in Northern California was particularly desperate. The region had only three reservations — Tule River, Round Valley, and Hoopa — to accommodate what had once been the densest Native American population in the United States. Kelsey discovered just why California’s situation was so extreme: the secret deep-sixing of 18 treaties with 119 tribal signatories negotiated by federal commissioners in the early 1850s that traded land for money, funded subsistence, and set up a reservation system. California politicians hated the idea of turning valuable real estate over to the state’s original inhabitants, and they fought so fiercely against the treaties that the Senate buried them in a secret archive and left most of the state’s tribes landless.

More than fifty years later, with the help of a clerk who had stumbled across the documents, Kelsey exposed the unratified agreements publicly:

Nowhere else in the United States have the Indian lands been taken without payment. Nevertheless the national government has gone ahead exactly as if it had acquired title, and has sold the land to settlers and others.

To demonstrate just how bad the predicament of Native Californians stripped of their homelands by the treaty debacle was, Kelsey, now serving as a special agent for the Office of Indian Affairs, set out to count all the state’s tribal people living off reservation. His 1906 report showed that the state contained at least 20,000 Native Californians, not the 15,000 the Census Bureau toted up in 1900. And the conditions many of these uncounted people lived in were horrific. Kelsey wrote that “the Indian in the northern part of this State has little to look forward to” and could expect only “a life of privation, ill usage, neglect, discomfort, without opportunity to rise or hope for better conditions.”

The NCIA sought to remedy this injustice by acquiring land for landless tribes. Using federal funds, Kelsey purchased 45 sites, all but a dozen in Northern California, and more were added after Kelsey left the Office of Indian Affairs. Known as rancherias to distinguish them from reservations, these small tracts served specific tribal groups. In addition, Kelsey helped Native Californians apply for land allotments in the public domain, including national forests, and advocated for tribal children to gain the access to public schools long denied them.

Unlike Muir and many of his contemporaries, Kelsey recognized how Native Californians had come to such desperation. They didn’t chose lives of landless, hungry poverty on society’s ragged edges, nor did they suffer from some evolutionary racial deficit that made their decline and extinction inevitable. Their population was, in fact, increasing, despite the deck stacked against them. Euro-American society had created Native Californians’ misery by sanctioned massacres, starvation through the loss of hunting and gathering areas, prejudice, religious indifference, and epidemics untempered by adequate medical care — the key tools of California’s state-sponsored and federally funded genocide.

As Kelsey told a meeting of San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club of California, the nation’s oldest public-affairs forum and a venue that drew the civic-minded:

The evils which the Indians suffer from the various forms of prejudice and neglect are for the most part beyond the reach of legislation. They are a reflection of public sentiment among white people.

Euro-Americans made this mess, Kelsey was saying, and now they needed to clean it up.

Muir could have paid attention to Kelsey’s advocacy, the way the Commonwealth Club’s members did, but he chose not to. And that’s on him.

Next: The long-walking writer who admired the Pueblo peoples.

Cast out of Eden at the Book Club of California

Monday, Jan. 13, 2025, 6–7:15 p.m., is the day and time for this event, which will be both in person at 312 Sutter St., Ste. 500, downtown San Francisco, and on Zoom. I'll talk about the book and take questions and comments from the audience. Free and open to all, with advance registration required for both in-person and online attendance. Details and registration here.

Pres. Biden adds two more tribally sponsored national monuments

Just yesterday, the outgoing president set aside two more national monuments, both in California and both sponsored by tribal coalitions.

Chuckwalla National Monument, located just northeast of the Salton Sea, encompasses 1,000 square miles of desert known for its striking rock formations, rare bighorn sheep, and ancient petroglyphs.

Sáttítla Highlands National Monument spans some 200 square miles in California’s remote and rugged northeast. The key feature of this landscape — which I grew to know well and love in the course of on-the-ground research for The Modoc War — is the Medicine Lake Highlands, a massive volcanic upland of deep forests, shimmering lakes, and sparkling obsidian flows long sacred to local tribes.