Wild Light from the Dark Side, Part 1

Sometimes those with the worst motivations end up doing something good, even if they didn’t mean it that way.

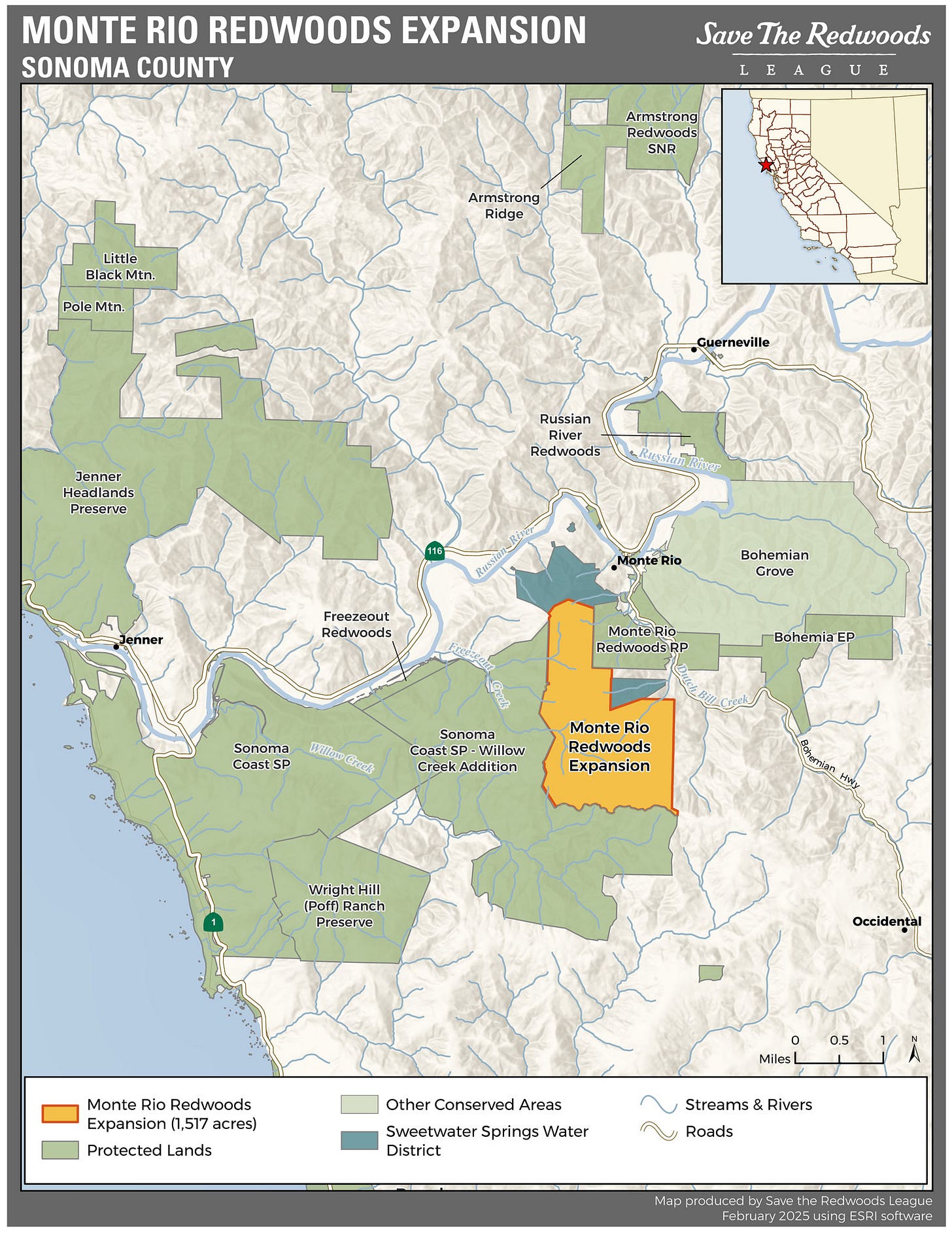

Only a couple weeks back, Save the Redwoods League made a drum-roll announcement. The league, a well-known California conservation group, had just finalized an agreement to purchase 1,517 acres of forest, streams, and meadows in Northern California’s Sonoma County. The parcel completes a corridor that totals more than 20,000 acres in a continuous greenbelt from Bohemian Highway to the Pacific Coast. “Together,” the league’s website proclaims to donors and partners, “we can conserve this land and reveal the completed puzzle’s picture of mist-cloaked forests, fern-lined streams, sunny meadows, and views that stretch unimpeded toward the horizon and the future.”

Given how close the Monte Rio parcel sits to Bohemian Grove, this latest acquisition brings full circle a story that began in one of the United States’ darkest places. It’s all about who the Save the Redwoods League’s founders were and why they created the organization in the first place.

Every July for almost a century and a half, the exclusive San Francisco–based Bohemian Club has hosted a gathering of members and guests at the 2,700-acre Bohemian Grove near Monte Rio. The men — and they are all men — represent powerful members of the business, political, and academic elite, and their annual gathering amounts to a throw-back frat party complete with skits, costumes, and adolescent hijinks.

In the summer of 1917, as this fabled gathering wound down, three of that year’s attendees hired a car and headed north. Easterners impressed by the experience of camping for the prior two weeks among old-growth redwoods, the three were off to tour the extensive domain of old, tall trees along California’s northern coast. They formed a distinguished trio.

Just coming off the successful launch of his popular The Passing of the Great Race: The Racial Basis of European History, the organizer and best known of the three was Madison Grant, an eternally dapper and endlessly wealthy New York City lawyer and organizer. His book, less an original work than racist ideas lifted from other writers and mashed up in a readable style that sounded authoritatively scientific, drew admirers from Teddy Roosevelt to Adolf Hitler. Grant argued that America’s white elites were being swamped out by swarthy, dim-witted, and morally challenged immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe — you know, Catholics and Jews. The Passing of the Great Race was that era’s equivalent of today’s far-right great replacement theory, and every bit as racist.

Joining Grant was long-time friend Henry Fairfield Osborn, a fellow New Yorker and member of Teddy Roosevelt’s Boone and Crockett Club for well-heeled big-game hunters. A vertebrate paleontologist by profession, Osborn gave Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor their scientific names and, as head of the American Museum of Natural History, became a leading public authority on science, something like Neil deGrasse Tyson these days. Osborn had helped Grant find the publisher for The Passing of the Great Race, and he shared much the same down-the-nose, white-supremacist views.

Completing the trio was John C. Merriam, the University of California paleontologist who had made a name by classifying vertebrate fossils collected at the La Brea Tar Pits, including the stuff-of-nightmares saber-toothed cat. Also a Boone and Crockett Club member, Merriam would soon leave the university to head the Carnegie Institution, which provided the principal funding for the Eugenics Records Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. A founder of the eugenicist Galton Society, Merriam shared Grant’s and Osborn’s faith in eugenic white supremacy.

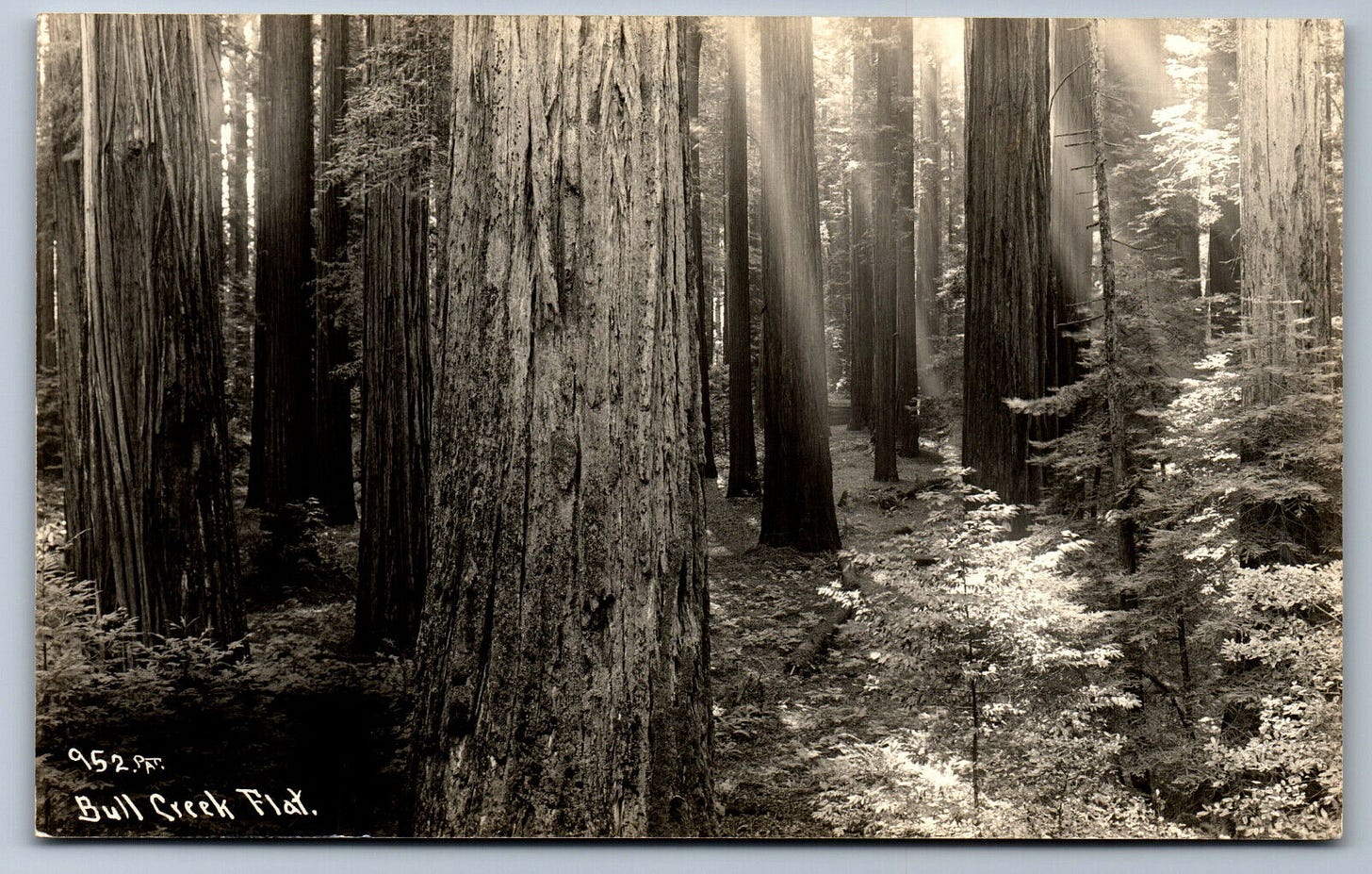

From the Bohemian Grove, the trio followed the coast north to Shelter Cove, then turned inland to the Eel River valley and onto a dusty, newly built highway. At Bull Creek Flat there came an epiphany greater than they had imagined.

“Suddenly we swung from the highway, dropping down a steep slope into primeval redwood timber,” Merriam recalled. “The car quieted as its wheels rolled over the leafy carpet. The road soon ended in a trail, and the party proceeded on foot.” Unspoken awe at the tall, ancient trees descended upon the three friends:

Like pillars of a temple, the giant columns spaced themselves with mutual support, producing unity and not mere symmetry. The men of the company, who all their lives had known great forests, bared their heads in this presence.

Then the contemplative silence was broken suddenly by the crash and crack of clearcut logging operations nearby. Given easy access to the old-growth groves by the same highway that had brought Grant, Osborn, and Merriam to Bull Creek Flat, timber companies were turning the nearby trees into lumber, railroad ties, and grape stakes as fast as ax and saw could fell and mill them. The three travelers were witnessing the end game of a long-term destruction.

When Europeans invaded California in the late 18th century, some 2 million acres of redwoods stretched northward along the coast from the Santa Lucia Mountains into what is now southern Oregon. Logging began in earnest as the gold rush in the middle of the 19th century suddenly swelled the market for lumber. By the time of Grant, Osborn, and Merriam’s road trip some seven decades later, only 4 percent of the original redwoods still stood.

Resolving to save the remnant old-growth groves, Grant, Osborn, and Merriam faced a tough reality: practically none of the redwoods were in public hands where they could be preserved by law, as Yosemite or Yellowstone had been. Timber companies and land speculators held title to practically all the surviving trees. The sole path to preserving the surviving stands was to purchase them at market price, then turn the acquisitions over to state or federal governments to be used as parks. Like the inveterate organizers they were, Grant, Osborn, and Merriam got to work.

Two years later, on Aug. 2, 1919, in the overstated, eight-story elegance of San Francisco’s Palace Hotel, the Save the Redwoods League came into being. Its strategy was to enlist wealthy donors from among the founders’ friends, neighbors, and associates and purchase parcels that would in time become parks. Over time, this approach, combined with political savvy and alliances with other environmental groups, set aside a complex of 66 federal and state redwood parks that today totals more than 220,000 acres of both old-growth and second-growth groves and welcomes more than 31 million visitors a year.

Were the three Save the Redwood League’s founders still living, they would surely celebrate the success those statistics signal, but they would also differ vehemently with the messages the league and the redwood parks send these days. In its beginning the league saw its purpose as more than preserving majestic trees. “There can be little doubt that [Madison] Grant identified the redwoods with the Nordic [Aryan] race,” writes biographer Jonathan Spiro. Like the tall trees, “the Nordics were now making their last stand in North America, where they were threatened with ‘a speedy extinction’ at the hands of invading hordes of immigrants.”

For Grant and his two founder friends, the struggle to save the redwoods was of a wild piece with the struggle to save the threatened white race. Just imagine how disturbed they would be to discover that next year the Yurok Tribe will be the owners and co-managers with the National Park Service of a new redwood park unit, the first such arrangement in the history of the U. S. national parks.

As you can imagine, there’s quite a backstory.

Up next: Wild Light from the Dark Side, Part 2.